-

Preface

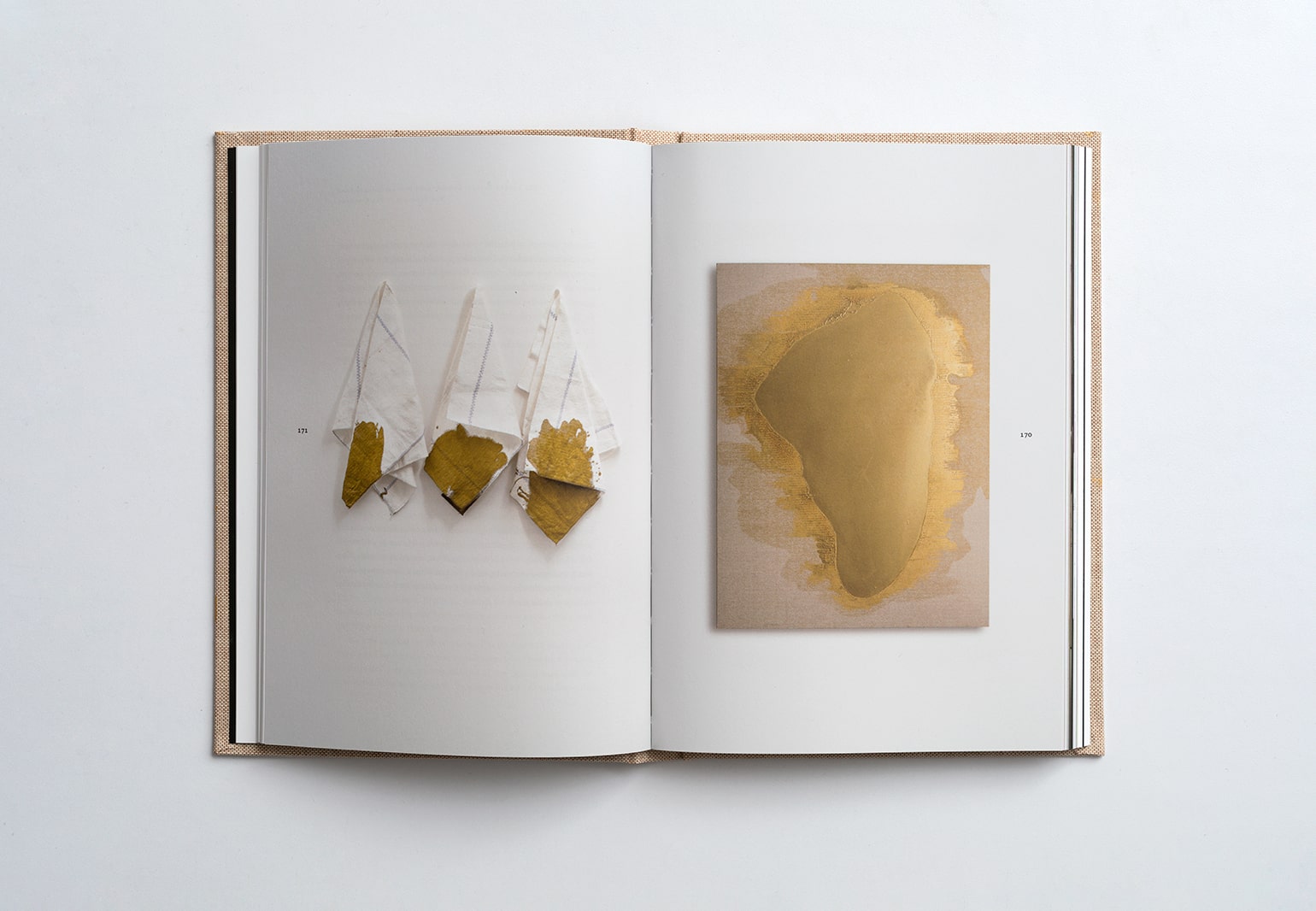

Different types of plants, some tied together with red ribbon and others gathered untied, are presented in Leor Grady’s photographic series ‘Bouquet’ (2015). The bouquets are photographed against dark blue velvet fabric commonly associated with Jewish ritualistic articles. They combine plants used by Jewish Yemenites for religious rituals such as havdalah, medicinal purposes, cooking, and some that are also believed to possess mystical properties. Grady collected the plants – basil, rue, khat and myrtle – in 2015 in the old Yemenite neighborhoods of Sha’arayim and Marmorek, in the town of Rehovot and in the Bilu neighborhood in the town of Hadera. “I realized that I had to find the elderly women, that they will lead me into their gardens. I believe these women know how to extract the plants’ medicinal potential. This knowledge has not really been passed down to the following generations. The plants set on the edges of kitchen tables were laid down almost indifferently,” says Grady.1 With his choice of photographic imagery Grady invokes the traditional use of plants by Yemenite women. Describing his artistic process, Grady refers to these women’s traditional roles, and by choosing the medium of photography he relates to the modern chapter of this tradition. Thus, the Bouquet Series is situated on a local historical and political crossroads of science, art, gender and race, and draws on the political and cultural contexts of its three structuring foundations: the photographic medium, the photographed subject and the photographic production process.2

The photographic medium: since the discovery of photography, visual culture in industrialized countries has had a central role in establishing and constructing the political realm.3 Photography enables the visualization of abstract political ideas, and remains a central tool for constituting colonialist, imperial, national and racial perceptions and orders. It is also central in establishing and stabilizing political systems, such as European Zionism, first as a national movement and then as a sovereign State – a cultural, economic and social hegemony.4

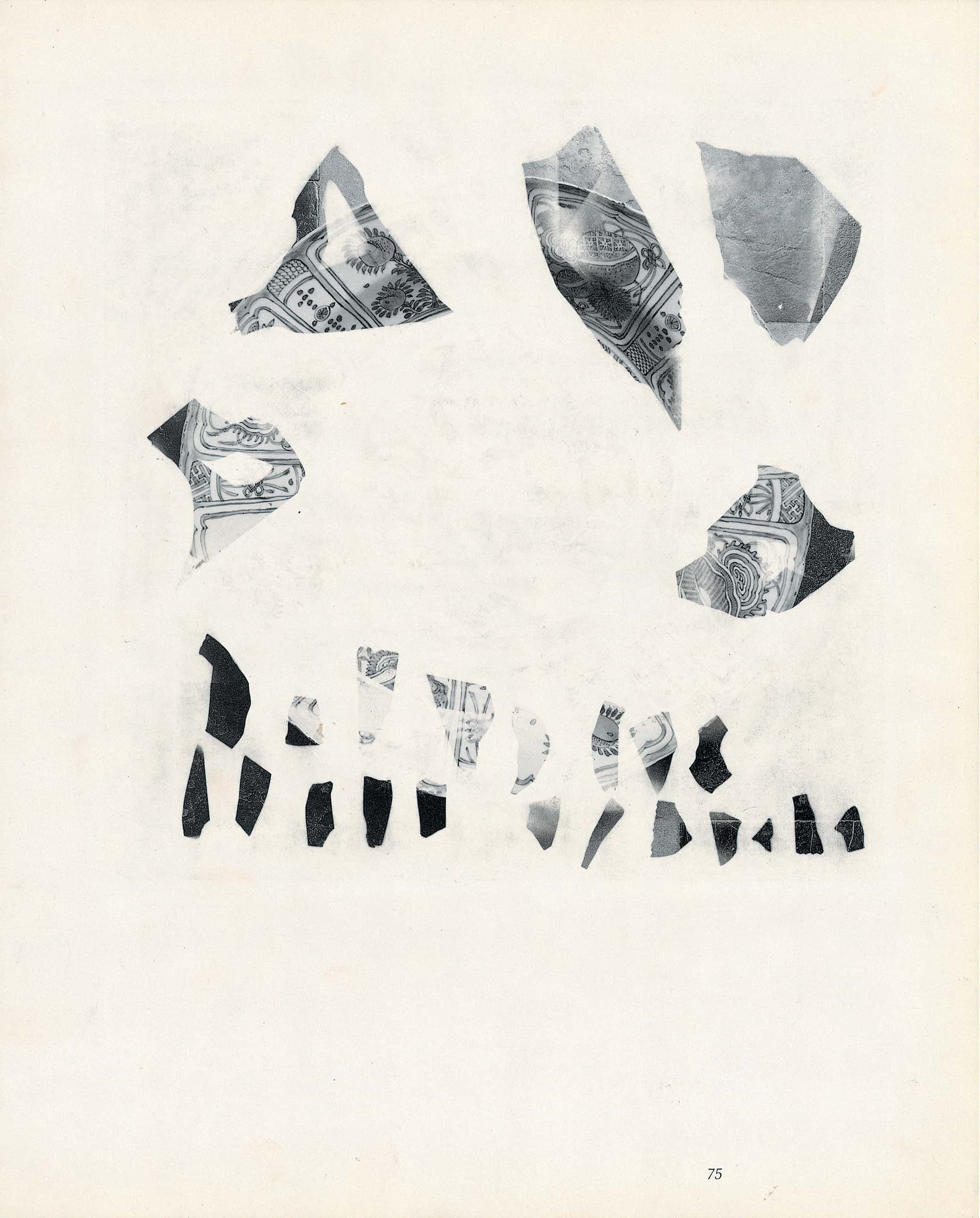

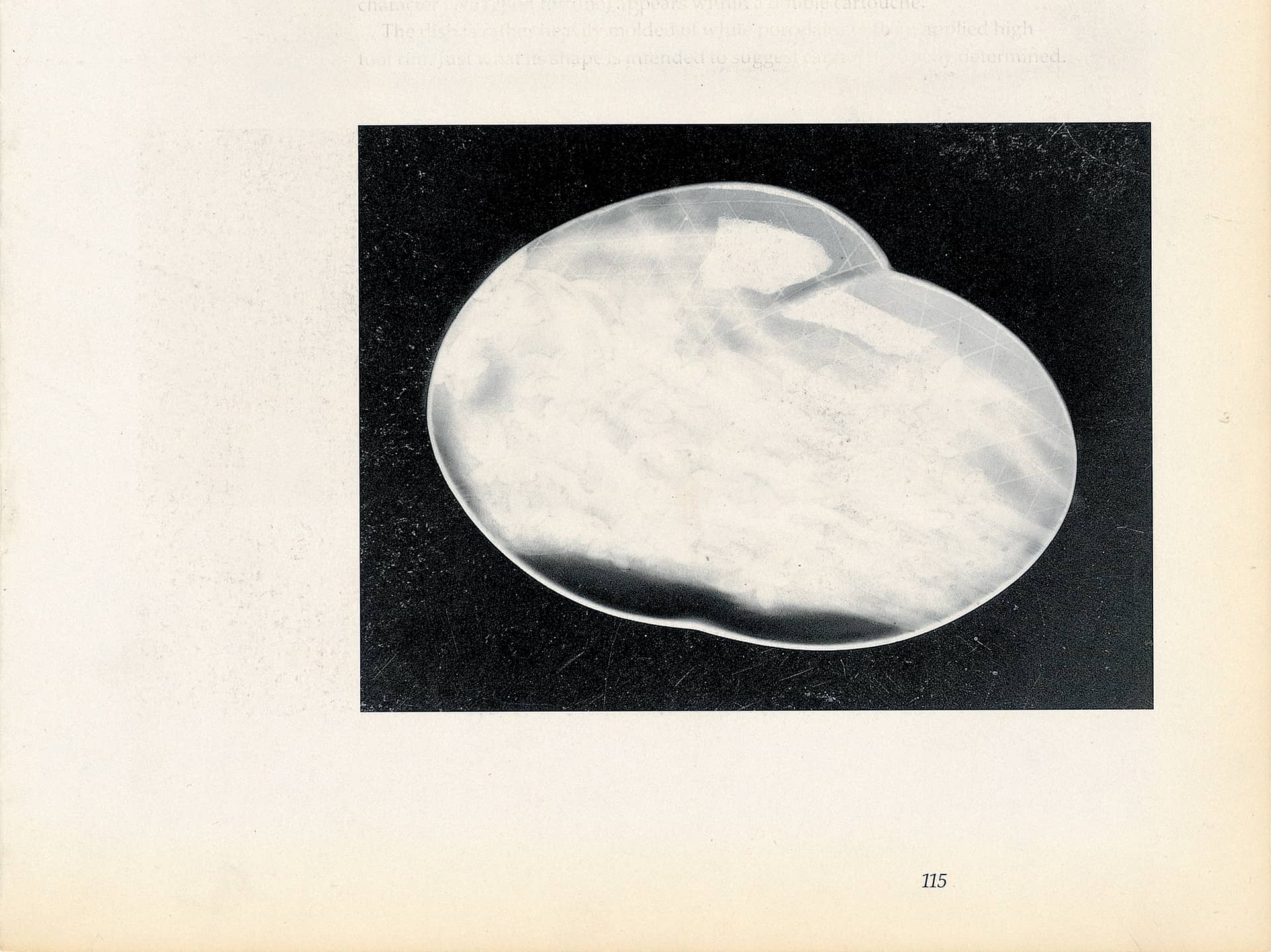

The photographed subject: just as photography is tied to the national and political arena, so too is Grady’s photographed subject. The plants in his photos are associated with ancient Jewish Yemenite traditions yet they are also arranged in modern, scientific botanic compositions. By the end of the 19th century photography was scientific botany’s main documentary tool, taking over from print, drawing and etching.5 Botany was part of the practice of classification and codification that came to the fore with the Enlightenment, and was used as a mechanism for constructing modern national identities, such as the German and the Zionist, reaching its peak with early-20th century racial doctrines. Both photography and botany were imported from Europe to Palestine by Ashkenazy Zionists who used them as tools to constitute a new political order and assert territorial control over Palestine, while simultaneously establishing differentiation and hierarchy based on race and gender.6

Early-20th century Ashkenazy scientists and photographers practiced illustration and botanical photography, as well as racial photography, in their new locality.7 Both types of photography seek to capture a “typical” (as opposed to singular) portrait of the photographed subject, be it plant or person, in an attempt to capture its transcendental essence.8 As Amos Morris-Reich has shown, Ashkenazy racial photography directed its lens at native Arabs and the local Jewish community, with Yemenite Jews being the most racialized group within it.9

The photographic production process: Grady’s description of the series’ production reveals his chosen social arena to be gendered. He attributes the cultivation of the plants to the women of his community. His process incoroporates a discourse of double loss – attesting to a disconnection with communal traditions and their agency. He had to search for the women and their gardens as well as their knowledge, which was not passed on to the next generation. Although Grady found the women and their gardens, they are absent from the photographs. Why did Grady choose not to photograph the women he met? What is the history of the intersection between botany and traditional plant usage? Between photography and Jewish Yemenite women? What are the relations between visibility and invisibility in the framework of this history? And how did the traditional rapture that Grady shows come to be?

This article traces the signs embedded within the Bouquet Series which refer to the beginnings of the history of visual racialization of Mizrahi (Eastern) Jews in Israel.10 This history is tied to the political transformations caused by the discovery of photography, which coincides with the arrival of cameras to Palestine, where photographers took pictures of local inhabitants, including Yemenite Jews.11 Thus, History was documented with cameras and presented as accurate data when in reality these representations produced the initial descriptions of symbolic intra-Zionist institutionalized violence — violence that has remained masked and unseen because its appearance has undergone a continuous process of naturalization.12 This photographed history contributed to the perception of Yemenite Jews in Palestine as a symbolic visual spectacle of a Mizrahi body whose racialization was screened and presented not only as its imminent natural aspect but also as the embodiment of its “nature”; hence in contrast to the culture that gazes at it. The restricted Mizrahi body is situated beyond the boundaries of symbolic temporal, spatial, and linguistic parameters that provided the framework for the Ashkenazy Zionist struggle to seize and ratify land in Palestine; the Mizrahi body is thus left out of that which European Ashkenazy Jews deemed to be the arena of the political present.

This leads to my central claim: racially derived classifications in early Ashkenazy Zionist society, which seperated capital owners from those subjugated to them, acquire a unique characteristic when seen through the role gender has played within this process. I argue that through photography, the physical bodies of Jewish Yemenite women became markers for racialized and gendered boundaries established by the Ashkenazy hegemony during the founding of the Hebrew Yishuv (the Jewish settlement in Eretz Israel, c. 1881-1948). This marking involves concrete and symbolic violence toward Yemenite Jewish women. Also, these borders neutralize the political dimension of these women’s actions by presenting them in ways mostly associated with human labor, with the sweat of their brows, in stark contrast to the appearance of actions of Ashkenazy women, who are shown in modes linking them to work and political action.13 The Bouquet Series appropriates the beginning and end by Ashkenazy Zionist history under the racial signifier of a “continuous past,” and the medium of photography as a central site for establishing this history.14 As a multimedia artist who rarely works in photography, Grady’s choice of this medium for the series is not coincidental. By placing the bouquets and himself at the center of the photographic frame, Grady positions them as both the central object of the racializing scientific-artistic gaze and the subject exposing and renouncing it.

-

1. Photography, Botany and Exhibition: Zionist Photographic Orders.

The Bouquet Series takes us back in time to the origins of the cultural bodies now known as “exhibition” and “museum” – the Renaissance cabinets of curiosity that appeared as part of an array of institutions and tools that established a new, racial-colonialist world order. These private displays, set up by nobles and learned European men, also included botanical drawings. The modern approach to plants and botany arguably emerged in the realm of art, through naturalistic depictions of flowers. These artworks complied with renaissance botany’s classification of nature into species and subspecies.

Cabinets of curiosity were part of the emergence of the new world order fashioned by “explorers”: white European men who set out to discover the new world now wondrous thanks to its resources, vital for enhancing their power and culture. Presented as new phenomena in the visual expanse, items in cabinets of curiosities illustrate the period’s new forms of knowledge and representation. As such, they resemble manifestations of progress directly linked to colonial power – the very political power which created the conditions of their appearance. The heterogeneity of the 2000 year old botanical culture resonates in the Bouquet series, which borrows from this historical legacy, activating and confronting several of its practices and notions. The series touches upon two of this history’s traditions: the preservation of plants for ritualistic and medicinal purposes, a practice common among Yemenite Jews from antiquity to the late middle-ages,.15 and the evolution of botany into a modern science which bore heavily on later political developments.

Whereas the 15th century cabinets of curiosities led toward the establishment of museums, and contributed to cataloguing processes which also enabled the creation of racial-colonial hierarchies, it was the 19th century World Exhibitions that brought this cultural-political development to one of its decisive maturing stages as a constitutive tool of racial-national orders. Renaissance forms of representation and knowledge were further developed in the 19th century when, inspired by Romanticism, the sciences – including botany – were established as disciplines and political tools in the service of nationalism..16 Influenced by these processes, World Exhibitions were designed and organized in European cities by travelers returning from voyages to “new world” countries. The exhibitions exemplify how visualization was used to illustrate political ideas on an unprecedented scale. They presented millions of visitors with objects marking the complete otherness of the East; illustrating and solidifying the political idea of Europe as a global, imperial, commercial hegemony and the East as the reservoir of her “natural” resources.

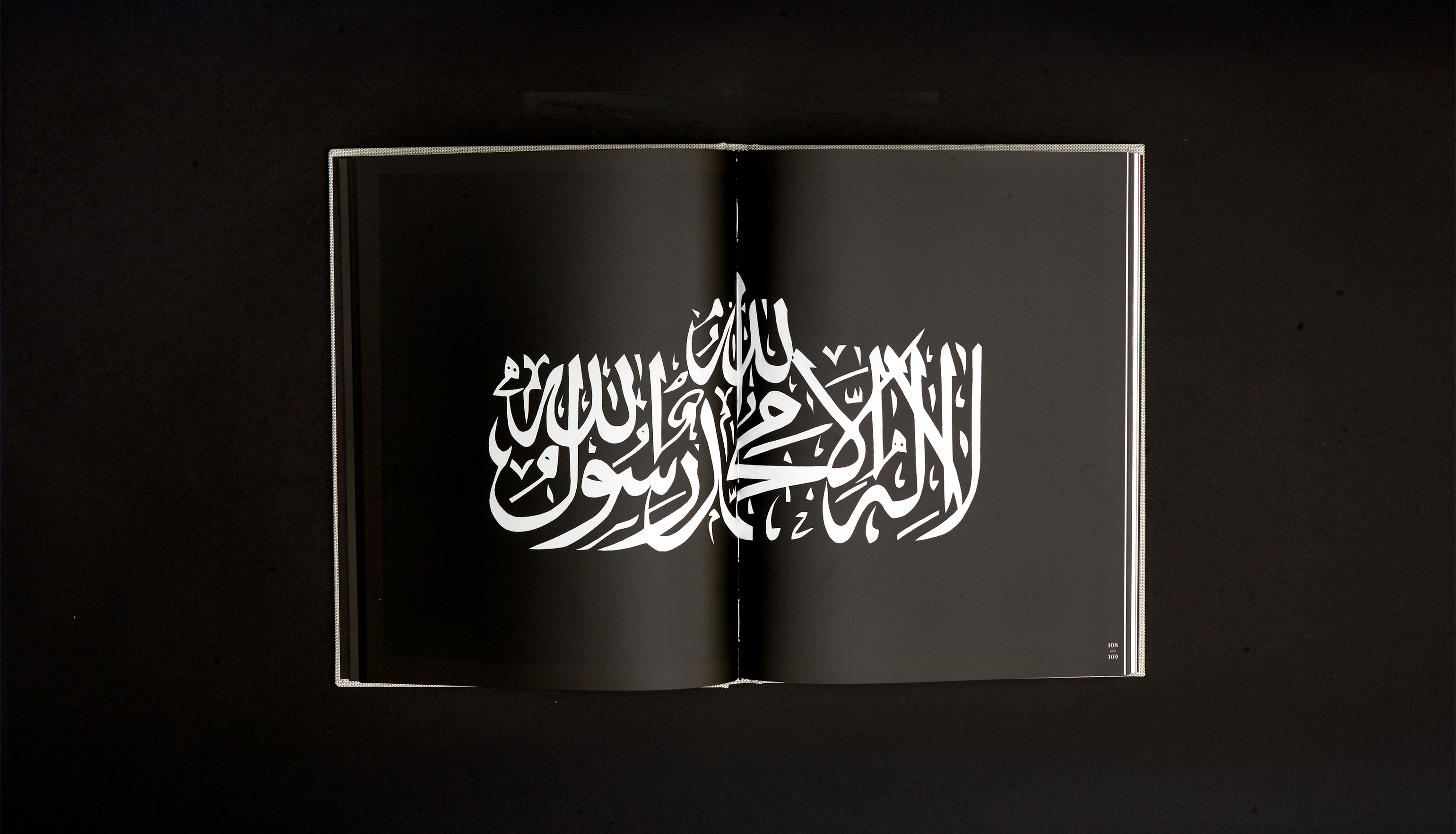

In the context of the World Exhibitions, photographic, anthropologic and botanical practices were utilized to create “world order as exhibition,” defined by visual culture researcher Timothy Mitchell as an order forming the racial borderline between what Edward Said termed “Orient” and “Occident.” Mitchell uncovers the exhibitions’ influence on global racial power relations and shows their role in establishing modern nationalism..17 Building on Said’s concept of the Orient as an invention of the Occident, Mitchell claims that the World Exhibitions organized by “travelers” and “explorers” reinvented the East, transforming it into a facade projected for the European gaze, providing the West with a sense of ownership over the geography and the knowledge of the Orient..18 The World Exhibitions also displayed “findings” discovered by European botanists in the “new world.” The botanical findings and practices, which in the renaissance created colonialist orders were now developed and directed at creating national orders: constructing identities, proving territorial claims, declaring land ownership and developing systems (linguistic, visual, material, spatial) for marking them. Traveling study expeditions seeking to identify plants or tour remote areas were used to induce emotional and rational bonds between nation and land. Methods forming a visibility of ownership over the visual expanse were developed to determine political ownership, thereby functioning as a main tool in the hands of the establishment. Construction of national orders informed national communities of the existence of a space of political imagination. This was largely based on an epistemological perception that marked the European individual as a cultured person and the Eastern individual as a product of “nature” which Europeans are meant to rule and control for their needs. Botany as its own modern scientific-artistic discipline, shaped in Europe between the 15th and 19th centuries, was imported and activated as part of the Zionist settlement in Palestine, where it was used to establish a territory-based national entity..19 The concrete and symbolic seizing of Palestine’s land was also achieved through designating plants as national symbols, publishing national botany books, and giving Hebrew names to sites, animals and plants – projects undertaken by Ashkenazy researchers in the fields of botany, zoology and agronomy, who used methods acquired in their European countries of origin.20 They were joined by artists of the Hebrew School of Art, Bezalel, established in 1906 by Boris Schatz in Jerusalem. Just as early modern artists had participated in scientific botanical projects, and 19th century artists had played a role in the emergence of national and imperial spheres, so too were Zionist artists active in the project of national resurrection in Palestine, with Bezalel occupying a symbolic role in this enterprise.

The Bezalel workshops of the early-20th century provided the setting for naturalistic drawing skills to act as a national social value.21 Students were required first to draw a plant naturalistically and then as an abstract model, breaking it up according to its typical schematic geometric shape..22 Boris Schatz cast his eyes upon the Zionist botany enterprise, telling art students that “In the way that scientific work educates people, so too, many will learn from your artistic work, which will help develop admiration to the world of flora and general good taste, something that is much needed here.”.23 From the early days of settlement these actions were intended to invent the native past of Ashkenazy Zionism and to establish it as an intra-Jewish hegemony. In this sense, Ashkenazy Zionism was Janus faced, like the double face of modern nationalism which looks ahead to a future of “progress” and modernity while simultaneously relying on the ancient, indigenous past of its members that, in order to provide validity, is at times invented..24

Animals, plants and the figures of Yemenite Jewish men and women were translated into images in systems of visibility in which the notion of the “native” past of the resurrecting nation was invented..25 In fact, they codified racial and gendered role divisions within the Jewish community. The inherent desire of Ashkenazy Zionism, to regain an “authentic,” “pure,” existence in the “Land of Israel” now conceived as a concrete territory, was based on European Romantic notions of a national past and its potential revival..26 It was also influenced by European concepts about the magic and exoticism of the Orient..27 These notions had consequences both in relation to native Arabs and to non-European Jews. The Ashkenazy establishment cast Yemenite Jews as “Oriental Jews,” marking them as both problem and solution: on the one hand, “authentic” and indigenous to the area, on the other, “primitive” and an antithesis to European progressivity and enlightenment..28

Yemenite Jews were given a double role in the hegemonic Zionist project. First, as a uniting factor: as figures thought to preserve the “authenticity” of biblical existence; some sort of archeological or ethnographic “finding” whose existence was presented as living proof of the Hebrew biblical past. This notion allowed Ashkenazy Zionism to legitimize its aspirations in the Middle Eastern expanse it set out to seize. Their second role was to differentiate: since they were thought to resemble local Arabs in what was considered primitivism, nativism, closeness to the land and to “nature,” it was easy for the Ashkenazim to pronounce Yemenite Jews as a preferred alternative to Arab Palestinians, as well as a source of cheap labor, thanks to one important difference: the Yemenites were “our native laborers”, or, according to the more common phrase, “natural laborers,” perceived as the opposite of the “ideological laborers” – the European Jews.29

Correspondingly, in addition to Bezalel workshops practicing naturalistic drawing of objects from the natural world and still life, there were also those teaching naturalistic drawing of Yemenite girls, women and men. Hundreds of objects designed by Ashkenazy Bezalel artists appropriated elements from the culture and appearance of Yemenite Jews, isolating, decontextualizing, and incorporating them in depictions of local flora, landscape and still life as orientalist visual images. These images were part of the process of establishing an Ashkenazy Zionist regime of knowledge seen through an intra-Jewish arrangement of racial classifications, constituting a new visual culture that marks “Palestine” for locals and European foreigners. Morris-Reich shows that intra-Jewish “racial photography” was already in existence in the first half of the 20th century.30 The first subjects of racial photography were mostly Yemenite Jews31 who arrived in Palestine in the “Aale Batamar” immigration of 1882, and even earlier.32

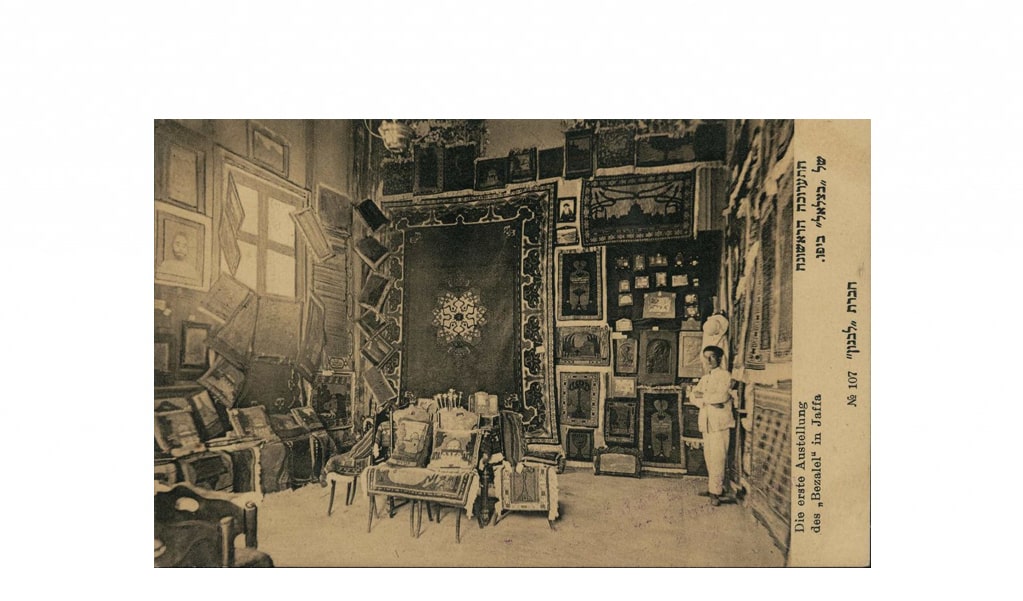

By designing images and mounting exhibitions, Ashkenazy artists and scientists actively established and assured a new European visual political imagination in the Palestine expanse, one which created racialized and gendered Zionist visual orders. Working according to the logic Mitchell associates with the World Exhibitions, these were meant to serve Ashkenazy Jews in different contexts. The imported and implemented institutionalized “exhibition” was a tool for constructing intra-Jewish racial differences and gendered hierarchies. A 1912 exhibition at Kinneret village “displayed crop produce, types of vegetables and livestock feed, domestically bred animals and various birds. At Sajera, local rocks, plants and animals were gathered for an exhibition. A special section of the collection was dedicated to historic remains.”34 Jaffa Lounge, founded at Jerusalem’s Old City Jaffa Gate in 1912, sold items made in Bezalel workshops and included a showroom with Bezalel products designed specifically for tourists (photos 1, 2). Still in 1912, an exhibition of Bezalel craftworks was held in Britain, one of many Bezalel exhibitions mounted in Europe as part of the art-school’s fund raising campaign.35 In 1916, Hanna and Ephraim Hareuveni founded a botanical museum of biblical plants in their house in Jerusalem’s Buckharim Quarter. The collection was then moved to the Hebrew University with its founding in 1925 (photo 3). Items from the collection were shown in Levant Fair exhibitions – international commerce fairs held in Tel Aviv during the 1930s (photo 4). The number of visitors at these exhibitions peaked at 60,000 in 1934. The fair’s architect, Arieh Elhanani, designed its oriental-style logo as a winged camel, known as The Flying Camel (photo 6). Architect Richard Kaufmann planned the fair’s central building, The Produce of the Land Palace, whose design, a ship facing east, also draws on oriental tradition (photo 5). These exhibitions contributed to establishing Ashkenazy Zionist visual orders, differentiated by offering an oppositional hierarchy to everything identified with the East – plants, animals, rocks and non-Europeans.36

European photographers were active in a period of colonialist expansion, functioning as messengers of both religion and empire. They showed their photographs to European residents who “were happy to see with their own eyes that there exists an undeveloped world (which they called ‘primitive’ or ‘inferior,’ and spoke about ‘inferior races’) that can be subjugated to great advantage.”37 They took upon themselves the role of arranging a visual inventory including photographs of peoples and “faraway countries, past assets” and “landscapes unfamiliar to European eyes.”38 The photographs of Palestine were fashioned according to the stereotypical oriental Holy Land, presenting its existence as concrete fact merely due to its availability as photographic subject.39

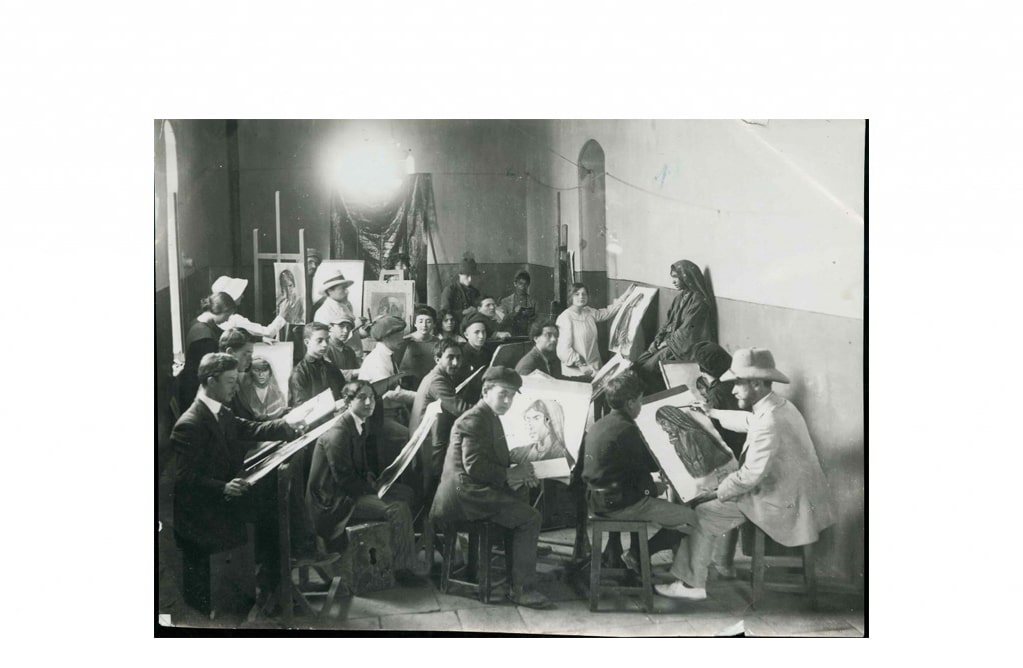

Ashkenazy Zionist leaders, either residing in Palestine or just visiting, also began using cameras to shape the story of the area from their personal subjective viewpoint, using a tool whose products were considered objective, and by so forming photographed hegemonic visual orders.40 Photography enabled a sort of framing and marking, transporting intra-Zionist racial-gendered signs beyond the field of art. Cameras facilitated an enlargement of the political effect involved in the creation of European Zionist visual orders in Palestine. This effect was exacerbated when, for example, the actual use of scientific-artistic practices of naturalistic drawing – whether of people or plants – was captured through photographs of the Bezalel workshops. When Boris Schatz and others took photos of Bezalel artists painting “Yemenite models,” they were in fact promoting the effort, as stated by him and others, to present the intra-Zionist order and its racialized and gendered hierarchy to European audiences, in an attempt to raise the funds necessary for establishing his institution (photos 7-8).41 Whereas the drawings and paintings signified a cultural order, these photographs signified the order’s racial and gendered political aspect in that they included the figure of the artist as creator who arranges the political order that produces the artworks. These types of photographs were taken at a time in which many key figures of the Zionist movement, including Ruppin, Jabotinsky, Hess and Nordau, were embroiled in detailed and heated discussions about the existence of a “Jewish race.”42 The logic at the core of these debates, which backed the claims of both supporters and opponents, suggested a clear link between such categories as “origin,” “blood relations,” “culture,” and “territory.”43 Already then, the visual racial signifier designed by photography tied visual characteristics framed in photographs with invisible characteristics deriving from that racial discourse.

-

2. Racialized Photography of the Political Present in Palestine

Photographing Yemenite Jews in Palestine extracts them from the time and space framing the Zionist struggle to seize Palestinian land, as well as from the narrative ratifying that attempt. By the first half of the 20th century, a Zionist cultural repertoire of photographs of Yemenite Jews had begun to accumulate. These photographs were received as documents attesting to the nature of the world, whereas in fact they presented a (seemingly scientific) racialized and gendered composition (seemingly artistic) of Zionist life in general.44

Drawing lesson, Bezalel, Jerusalem 1912, Israel Museum Collection, Jerusalem.

Photos 7 and 8 present a visualization of the political division of roles in both time and space, by granting visibility and ratification to the logic of Zionist disciplinarian actions: the botanical drawings on the workshop walls in photo 9 (botany as an Ashkenazy Zionist discipline led by botanist Ephraim Hareuveni and his partner, Bezalel artist Shmuel Charuvi), the art classes (art as an Ashkenazy Zionist discipline led by Boris Schatz), the intra-Jewish classifications (sociology as an Ashkenazy Zionist discipline led by Arthur Ruppin), and the practice of documentary photography (by Y. Ben Dov and Leo Khan, for example).

Unknown photographer, Students at a drawing lesson, Bezalel, Jerusalem 1909, Israel Museum Collection, Jerusalem.

Only the products of these disciplines appear in the photographs – objects and relations between people – and this visibility is marked as fact, as the “nature of things.” An invisible ideological background arranges the order of visible objects now framed by photography as innocent or natural compositions, analogous to reality itself.45 This same ideological background is also responsible for locating, gathering, classifying, identifying and defining the roles of groups within the “Jewish diaspora.” All the while, Jews from Arab and Muslim countries were categorized as a reservoir of “human resource,” vital for the Zionist demographic agenda, with Yemenite Jews cast in a central role.

Photos 7 and 8, depicting what Boris Schatz called the “original models”46 as seen in drawing classes, use symbolic visual means to illustrate the political role division in time and space. Modern western clothing is identified with the present and the future, which dominates most of the frame, while the traditional eastern clothing associated with the past is situated on the fringes of the frame. The dynamism and activism of the painters – as opposed to the immobility and passivity of the “model” – is further exacerbated when the model is a Yemenite man, as in photo 9, where he is feminized by being placed on the same level as the woman. Role division in space is symbolized through the clear spatial separation between the position of the passive, immobile, and distinct Yemenite “model,” and the position of the active, dominant, ordinary majority. The ordering of signs arranges a hierarchal relation between “progress,” associated with modernity, vascillating between present and future, and “tradition,” associated with the past. Within this worldview, Yemenite Jews are placed symbolically outside the political present in Palestine and its constituting conflicts over territories and historical narratives. These symbolic separations are also present in photographs showing only one “group,” as well as in non-figurative photographs. The photographs of the “Yemenite village” in Ben Shemen (established by Boris Schatz specifically for Yemenite Jewish workers) recall the spatial, geographic, physical and communal separation between Bezalel’s “natural” and “ideological” laborers – the latter being the “artists,” to whom the village belongs. These photographs in particular show the signs of poverty and meagerness surrounding the Yemenite male and female workers, in glaring contrast to the signs of wealth and abundance seen in photographs showing the products of their labor (photo 2). Photo 1 shows the Gate pavilion which, despite its emptiness, is still a spectacle of the racial signifying order. Although the structure is made of tin, it is different from the type used in the shacks and tents housing the new nation’s “natural laborers.”

Yaacov Ben Dov, The Bezalel Pavilion near Jaffa Gate (postcard), Jerusalem 1912, Yad Ben Zvi Collection.

Unknown photographer, The first exhibition of the Bezalel Pavilion in Jaffa, The Zionist Archive.

-

3. Racialized and Gendered Photography of the Political Present in Palestine

Above all, the Bouquet Series symbolizes the story of Yemenite Jewish women in Mandatory Palestine: women captured by photography situated within the limits of the period’s political restraints, demarcated for them by the European Zionist gaze, as well as women who were not photographed because they transgressed these limits. The principle guiding hegemonic photography of Yemenite women in Mandatory Palestine derives from the renaissance model painting tradition that normalizes female bodies as objects to be examined, compared, discerned, measured, gendered and judged by the subject, the maker – the artist holding the paintbrush of “culture.” This tradition is rendered in photo 3, in which a young girl stands on a raised chair before a group of painters.

In Hebrew books that include photographs of Bezalel students and workers, the students are named whereas the workers, some no more than children and youths, are barely mentioned. The only source that refers to the identity of the model in the photo identifies her as “Mazal the Gypsy”.47 Although there was a Gypsy community in Jerusalem at that time, Mazal is a Jewish, particularly Yemenite name. Boris Schatz held that “Closeness to the Biblical spirit is achieved by depicting biblical characters with figures of bearded Yemenite men.”48 Indeed, Yemenite male models appear in early-20th century photographs of the few workshops for painting and drawing at Bezalel. Therefore, it can be assumed that if the young woman was in fact a gypsy, her role at the Bezalel workshop was similar to those given to Yemenite men: a means for “expressing the links between the regeneration of modern Zionism and the biblical golden era, the land that was the birth place of the Jewish people, and the period in which it dwelt in its land.”49 The artist has organized the “nature” appearing before his gaze so that it will acquire meaning within an order of appearance that serves and supports that “culture.” Hence, the “model” is a resource, a raw material for creating images that will grant the painter symbolic social, economic or cultural rewards. As John Berger shows in his groundbreaking study Ways of Seeing (1972), this tradition creates a profound cultural foundation that naturalizes the hierarchal gendered role division according to which men’s recognition of women is shaped by the active examining gaze, which places their bodies as signs on the world map of objects they encounter: animals, plants and inanimate objects.50 Although Berger does not address racial differences marked by the male gaze, other writers show how the bodies and appearances of “oriental” women were placed on an even lower rank in the hierarchy of objects presented to this gaze — as matter, as body, as resource. In the words of Edward Said, as a realm of “not only fecundity but sexual promise (and threat), untiring sensuality, unlimited desire.”51 This notion resonates in Zvi Schatz’s musings of his experiences of Eretz Israel nature, “This rushing spring, merry and fertile, aroused desire in me, the desire to be merry, wild, to fertilize women, many women! Just like that, as though they are ‘savages,’ strong children of nature, and their force, our gain.”52

This tradition is also seen in photo 10, in which two smiling female Ashkenazy art students appear beside an oriental looking female “model.” The photographer of this image, Tsadok Bassan, left no clue to the identity of the model, yet like many other photographers he owned garments worn by Palestinian women and men and staged many photos showing Jewish men and women wearing them. As in the case of the “Gypsy” woman, it makes no difference for the photographer whether the subject is Yemenite, Bukharin or Arab, as she serves the same purpose: creating an oriental image that unites Jewish past and present.53 All the women in this photograph stand in a row with their bodies facing the camera, each in the midst of an action. In this respect, they are leveled in the hierarchy of power relations between photographer and subject: he is the subject, they his objects. However, the connotations implied in the actions of the women create differences and hierarchy among them. The action of the Ashkenazy artists, at the photograph’s left, is not detached from its surrounding working environment – in fact, the actual placing of the “model” is what justifies this working environment, whether indoors or outside. Their gazes are turned toward the model and they are seen drawing her, in the present time. Although the model also faces the camera, actualizing her subjectivity, her action is detached from her. As such, she evokes connotations of an action that is representational as opposed to actual. The represented time is the past, and the contrast between present and past is further strengthened through her traditional, as opposed to their modern, clothing. Moreover, whereas the female painters are indeed photographic objects they are also presented as subjects in relation to the model, who therefore is doubly signified as object: once, for the photographer, and once for the female painters. Finally, the action of the eastern looking woman evokes human “toil,” the kind of survivalist labor connected to basic existential needs. This is opposed to the actions of the female painters which connote work and creation, and are tied to the existence of culture.54 Taking into account that the period’s art scene served the Zionist project, and that painting was perceived as a political act, the actions of the Ashkenazy women were given a political value along with the value of their work.55 The action of the eastern woman is therefore linked in the photograph to “nature,” a realm considered apolitical; thereby blurring any political potential that could be implicated in her action.

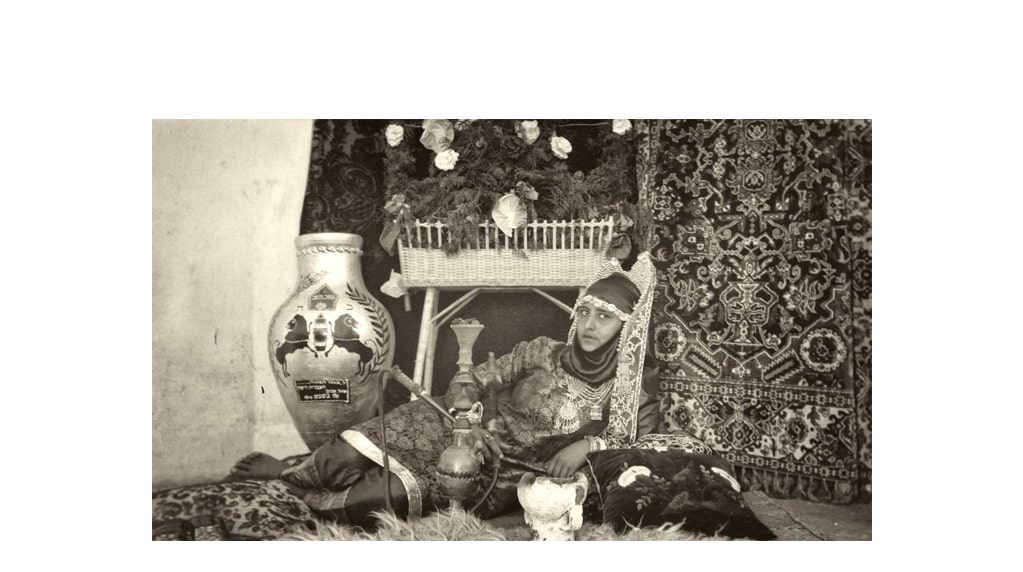

Other photographs of Jewish Yemenite women from the early-20th century are based on the same foundations: 1. They capture an action associated with basic existential needs – as can be seen in photos by Yaakov Ben Dov of Yemenite women in the Sha’arayim neighborhood (photo 11). 2. Appearing in a “Yemenite entertainment show”56 – especially Purim celebrations, an event in which Yemenite women are obliged to portray the visual role of the oriental woman forever immersed in her traditional past, as in the Shimon Koberman photo showing Tzipora Tzabari, who was crowned Hebrew Queen Esther during Purim 1928 (photo 12).57

Zipporah Tsabari, who was crowned “The Hebrew Queen Esther” and her ceramic jug award, 1928.

As elaborated by Vicki Shiran, Henriette Dahan-Kalev and others, this political role division between Mizrahi and Ashkenazy women was in place from the early beginnings of Zionism and is still in place today.58 Distinctions based on class, race, and gender construct hierarchy between Ashkenazy women, presented as situated within the Zionist political present, and Mizrahi women, who are placed outside it. Analysis of these photos presenting the figures of Yemenite Jewish women shows that the realm of the political present, itself framed with racialized boundaries by Zionist visual orders, is even more significant in light of another classification: gender. In parallel to institutional museum displays dealing with eastern Jewry since the establishment of the State of Israel, these photos also treat “eastern women” as a central exhibitory element through which Mizrahi Jewish culture is gendered. As Noa Hazan shows, feminizing was used as a significant organizing element and as a weak discursive position in the male/female binary. This situated Mizrahi Jews under the gendered markers of neediness and constant dependence as opposed to Ashkenazy Zionist nationalism which was formulized as a protective and emasculating movement. This process added a hierarchy of gendered signifiers to that of racial signifiers, and thus strengthened it.59 These power relations are visible in the photos of the Bezalel workshop drawing lessons which, to use an organic metaphor, expose the roots Grady sets at the center of the Israeli art field: one based on familial, white, patriarchal relations. As Sara Chinski argues, gendered and racial role divisions established at Bezalel are reproduced and preserved in the Israeli art field and still persist,60 regardless of the diminishing stature of naturalistic genres.61

-

4. A Photograph that was Not Taken

In a sense, The Bouquet Series is this history’s “untaken photograph”; it unmasks Zionist nationalism’s biological metaphor of birth-rooting- growth with both symbolic and actual signs of racial and gender violence. The visual orders of Zionism’s racialized and gendered political imagination were not only formed and stabilized by the selection, classification, and design of photographic subjects; they also involved erasing the marks of violence in an attempt to constitute them as “natural” – as phenomenon devoid of the mediation of culture and its creators.

Some of the plants in Grady’s bouquets are photographed with their roots exposed and seem to have just been pulled out of the soil. In light of the scientific-artistic approach presented above, these images recall the practice of modern botanical drawing, in which the gaze of the European artist or scientist charts the plant, its stems and its roots. Yet as mentioned, Grady ties the bouquets to another aspect – that of the Yemenite women who still cultivate them in their gardens. Whereas the deep blue velvet fabric on which the bouquets lie signifies continuation of tradition, religion and faith, the bouquets are photographed separately – cut and uprooted – thereby inducing feelings of grief and loss. Why did Grady choose not to photograph the women in whose gardens he visited? The absence of these women recalls the female Yemenite models in Bezalel workshops, as well as those who weren’t photographed because they crossed the political boundaries of time and space marked out for them by the Zionist gaze.

I will refer to these missing photographs through ‘potential’ descriptions of them derived from testimonies written in and about that period. The role and place of Yemenite female laborers at the Bezalel workshops was not different from their role as agricultural laborers in settlement fields. The Dan Almagor poem Dry Branches, which was censored time and again from the moment it was written in the early 1980s,62 tells the story of Yemenite women and the story of their photographs – those that were not taken. The poem recounts a public lashing of Yemenite women by the farmer Yonatan Makov which took place in Rehovot in 1913.63 The poem evokes images of an untaken photograph, whose appearance would have damaged the unity of the Ashkenazy Zionist visual order and culture, and exposed the violent conditions that enabled it. Photos of Yemenite women and men taken around that same year present them embodying the role assigned to them by the Ashkenazy landowners. Untaken photographs tell the story of an unspoken language, which Almagor calls the “language of lashings.”

-

Dry Branches by Dan Almagor

Everyone talks about the “good old years” Yet in the town Rehovot every Yemeni

Still recalls the case of farmer Yonatan When he caught two Yemeni women

At dusk, in the vineyard gathering

Not grapes, but only dry branches,

Dry branches,

Dry branches to burn in their stove.

He grabbed them both did farmer Yonatan And beat their backs at length with a whip, And the beatings are as hard as dry branches, Dry branches.

Then with thick rope he tied the two

To his donkey, to the end of his tail, And so, sitting proudly

He rode into town

And on the main road, for all to see

A farmer on a donkey, his whip held high

And the two women dragged behind,

Tied with rope to the donkey’s tail,

Two weak, scared, humiliated women

Who had tried to gather some dry branches,

Some dry branches.

Tied to the rope, as if led to the hanging,

And all the townspeople watch in silence,

And they all know:

Yonatan comes from a good family.

And cries Yonatan: “this is what thieves deserve, To be tied with rope to a donkey’s tail.”

What did they steal? The whispers abound,

In the vineyard they gathered dry branches

Some dry branches

Dry branches??

Dry branches! On the top of the hill a bell resounds,

And the crowd gathers on the main road,

And the farmer rides and waves to a friend,

The street is long and busier than usual.

The women walk, their gazes cast down,

But know that watching them is their little boy. And on the main road, right there on that wide road He sees his mother tied to a tail,

He sees his mother held by her neck

Dragged, humiliated to the ground in the street. He sees everyone watching in silence. He sees smiles and hears a call

“Mom, came and see! A parade!”

And all the townspeople know:

Farmer Yonatan comes from a good family.

And some say: He did well, that is good. So they will know, they will see that stealing is forbidden. And the son looks on. He was taught in the “heider” About the innocent child who was almost sacrificed, And here in the street, for everyone to see,

The mother is lead to sacrifice,

And instead of a knife, the whip cuts.

And wood for the burning – a bunch of dry branches Dry branches…

Yes, many years have passed since then

The son is a grandfather, his hair has greyed.

And many memories have faded and passed

But he will never forget

That dusk…At the center of the poem, in the middle of the third verse, the phrase “he sees” repeats four times. Into the field of vision of the son of one of the beaten women enter harsh images of violence directed at a figure he recognizes: his mother. The poem marks the traces of a field of vision censored by the period’s photographers, as well as the violence establishing the Ashkenazy visual order’s border between visibility and invisibility. Shulamit Levy describes the “language of lashes” as one used by the Ashkenazy landowners to show Yemenite young girls and women their place within the racial and gender role division:

I will never forget the appalling welcome we received, when I was a child and young girl, from the Zikhron Yaakov farmers. We were housed in cowsheds and stables and treated like lowlifes […]. During harvestings, only few farmers allowed us to take harvests from the fringes of the fields or gleanings from the vineyards. We had to dig up the mice tunnels, for their hordes of grain stalks. […] We were abandoned, and denied and even lashed, unbelievably, for collecting twigs and branches the farmers had thrown away. The language of lashings was that most commonly used, along with shaming and humiliating. Not to be remembered in favor is the famer N., who would harass us with a whip and was mean and evil, even hitting women with his whip.64

From Levy’s account it transpires that when Yemenite women created a continuous line between the orders of their life in Yemen and those of their lives in Palestine, following the ancient tradition of gleaning harvest leftovers, they were in fact treading between the safe territorial boundaries of their original tradition, which promotes intra-class solidarity. However, as part of the new geopolitical context into which they arrived, they were treading exactly in-between territorial boundaries set according to an opposite logic – one of abandonment – which made the flexible intra-class traditional boundaries harsh and violent.

As mentioned above, the practice of gathering, assembling, classifying and using the Palestine plants was central in the attempt to realize national territorial validity. By transgressing the demarcations set for them by the Ashkenazy establishment, Yemenite women were actually placed on the same rank as its enemies in that their acts were seen as threatening the role division between owners and those subjugated to them, between male masters and female laborers. According to Ella Shohat, “The same historical process that saw Palestinians disinherited from their property, land and political-national rights was tied to a process disinheriting Arabian Jews from their property, land and roots in Arab countries; and within Israel – of their history and culture.”65

Smadar Lavie, who links the dry branches even to the evacuation of the residents of Kfar Shalem, considers the incident to be a symbolic initial occurrence in the general ongoing Mizrahi struggle, in that it deprived Yemenite Jews of any connection to land ownership in territories that later became the Jewish State, where they lived as second rate citizens. “Not a lot has changed since,” writes Lavie, “as part of the relation between Mizrahim and masters, Yemenite and Mizrahi Jews […] as a community, remained without legitimate land rights and without economic stability.”66

Young Yemenite girls and women who dared revolt and cross the boundaries of time and space demarcated by the Zionist political present were directly punished – the whip being both the intimidation marking the line and the punishment for crossing it – which reduced their being to that of body, situating them in the role of “nature” that threatens “culture.” This role division also set the logic and limits of the Zionist field of vision, as is seen in photographs of Yemenite women from the period. These “bloody” limits are marked through violence and bloodshed.

The “language of lashings” continued to serve the Ashkenazy establishment for decades, as testified by Joseph Tzadok, a Jewish Agency envoy at the Hasahd camp in Yemen. In the years 1948-1949, the camp gathered tens of thousands of Jews from around Yemen in preparation for the Flying Carpet mission. The camp “was ruled by a regime of violence […]. It was a closed detention site with a sadistic attitude toward immigrants, weak and fragile in body and soul, who received horrible daily beatings with whips and sticks.”67 This description presents a very different picture than that of his colleague Shlomo Yeffet, who was also sent to the camp by the Jewish Agency.

Although testimonies of violence toward Yemenite Jews, especially women, are mentioned in books and documents about the period, there are no photographs documenting the events. “It is time to discuss the missing photographs, not those lost, but those never created,”68 writes Ariella Azoulay. “Civilian vision cannot recognize the censured boundaries or fields of vision dictated by those in whose power it is to prohibit access to the photos,” or to the act of photography itself. The limits of the field of vision as they emerge from early-20th century photographs of female and male Yemenite Jews avoid “capturing the subjects as bearing grievances, and whether the archive prevents their appearance as such, the viewer can still participate in the event of the photograph and change the terms of the appearance of the accusation.”69

-

Conclusion

The Bouquet series recontextualizes this site by reversing the established order of gazes; Grady demarcates the Ashkenazy male hegemonic viewpoint to which he himself is subjected and turns it into an object now set before his gaze. This process allows him to dismantle the symbolic racialized and gendered Ashkenazy role division while addressing its institutionalized invisible violence. In so, the Bouquet series marks a shift from institutionalized representations of Yemenite Jews to the thing in itself, which rearranges the dialectic of visibility that marred it in the past and is still present now. This shift is part of a wider trend in current Israeli culture, which sees larger numbers of second and third generation Mizrahi Jews writing their history and expressing their claims, in first body present, turning the gaze from institutional to independent visibility.70

Venice Biennale For Architecture, Artis, The Jack Shainman Gallery, Printed Matter Art Book Fair, Alon Segev Gallery, Chelouche Gallery, Braverman Gallery, UMapped.