-

I Eritrian and Sudanese Refugees in Israel: A Reckoning

For many years the only ‘refugees’ spoken about in Israel were the masses of stateless European Jews unable to find sanctuary from the perils of Nazism. The M.S St. Louis left Germany in 1938 with a boatload of emigres, only to be turned away from every single port they docked at. All nine hundred passengers returned to Germany. Only two hundred would survive the Holocaust. Israel’s creation was justified by the burning belief that no people should ever be subject to such horrors.

One would think the frequent invocations of the Holocaust in Israeli public discourse would render consensus sympathetic to the suffering of any victims of genocide, yet the the fate of the Eritrian and South Sudanese refugees fighting to remain in Israel has largely been met with contempt and derision. At a protest in 2012 Likud MK Miri Regev now the minister of Culture and Sport, went so far as to say “the Sudanese are a cancer in our body.” And yet in 1951, Israel was one of the first countries to vie for the creation of the Convention On Refugees, whose mandate was to define and outline the rights of individuals seeking refuge and asylum after World War 2 (WW2). According to UNHCR: “The core principle is non-refoulement, which asserts that a refugee should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom.” While Israel has largely abided by policies of non-refoulement, it has also implemented policies aimed at making the lives of refugees so untenable many have left of their own resolve.

Since 2006 a steady stream of Africans fleeing from the military dictatorship in Eritria, and the civil war in South Sudan have illegally crossed the Egyptian border into Israel. Though Israel has since erected a border fence, curtailing the possibility of further immigration, and though these new populations have nearly ceaselessly integrated into the local labor force, the Israeli government, media, and consensus have recently initiated a campaign aimed at deportation. There is little question that a return to Africa would further endanger this already vulnerable population, a risk compounded by the presence of torture houses in Sinai where hundreds of African migrants have been held for ransom. For many, reaching Israel is a matter of life and death.

While the recently hatched plans to forcibly deport the refugee community have been shelved due to a decree by the supreme court, it is more crucial then ever to present a synthesized and factual timeline of this story; to investigate and hold accountable state formulated narratives which brand the ‘refugees as infiltrators who pose a dangerous threat towards Israeli cohesiveness and security.

But why is there such rampant skepticism towards multiculturalism? And public opinion notwithstanding, why is it that aside from massive demonstrations, Israeli’s have so few avenues with which to influence legislative mechanisms within the Knesset, which this November voted 71 to 41 in favor of deporting the refugees to an unknown African country.

A major policy reversal of non-refoulement had taken place without with any significant increase in public discussion on the matter. In distinction to the American system, where a barrage of emails, phone calls, and protests directed at the offices of many members of congress succeeded in swaying elected representatives to resist Trump’s travel ban – the Israeli political system does not enable citizen’s to sway MK’S voting patterns through the ballot box. Israel boasts a unitary parliamentary system based on proportional representation, heralded by many as the Middle East’s sole democracy. This means that citizens can only vote for a party, not for an individual representative geographically bound to represent them. So long as a party receives over two percent of the popular vote, they receive a proportional number of seats from the 120 seats which constitute the Knesset. The party with the majority of seats is invited to form a government, either based on its majority, or its ability to form a coalition with likeminded parties.

As opposed to the Canadian and American systems, the Israeli system invests within each party the power to select their delegates internally according to a ‘closed list’ system – where the representatives are internally selected by each party according to their own rules and regulations. As the country is not divided into voting districts, independent media, grassroots campaigners, and citizens are deprived of the possibility of targeting and monitoring elected officials so as to keep them accountable to their campaign promises.

-

II A Changing Society: Privatization & Migrant Workers

Neve Shaanan is a small parcel of land tucked between Tel-Aviv’s central bus station, and the cities Southern neighborhoods. Constructed according to a menorah shaped urban grid, it is today home to tens of thousands of refugees from Eritria and South Sudan, alongside a significant population of foreign workers and Israeli’s. Once known as ‘The Shoe district’ due to its large concentration of shoe importers and manufacturers, it is always been a socio-economically depressed area, largely owing to the presence of Tel-Aviv’s central bus station, and its long standing neglect from city hall.

The neighborhood’s location and price range made it a desirable location for many foreign workers who began to come to Israel at the behest of the government in the early 1990’s. Following the end of the Intifada the Israeli economy began to look for a solution to replace the large Palestinian labor force which had for years crossed daily into Israel, working largely in construction, maintenance, and other ‘undesirable’ jobs. The government began to encourage migrant workers to come and work in Israel – with one stipulation: Familiar with the European context, where migrant workers who naturalized begin to transform the socio-economic realities of their host countries, Israeli ministers devised a purposefully ambiguous set of immigration policies and procedures designed to exploit cheap international labor, while also preserving Israel’s ‘Jewish’ character. As opposed to Europe – neither the foreign workers, nor their children, would ever have the opportunity to become permanent residents of Israel. A series of legislative protocols were enacted to ensure just this.(2)

The 1990’s represented a significant turning point in Israel’s neo-liberal transformation, where the country was opened up to private investment, government owned industries were privatized, and real estate speculation would dramatically change the cost of living. These changes have consistently privileged the wealthy classes and resulted in large feelings of disenfranchisement amongst a middle class which continues to struggle for its survival.

Privatization opened the economy up for global investment, creating a new social structure of capital linked to the globalized economy. It is in this context that the African asylum seekers began pouring across the border; without a stable legal status – and unable to be deported due to humanitarian concerns in Sudan and Eritria – the refugee community was forced to huddle together, often living five people to a room in order to survive. Exploitative real estate practices in Neve Sha’anan evolved in reaction to an overall reluctance to rent apartments to Black Africans, where local landlords began charging the refugees per head – resulting in a situation where their ‘collective rent’ for neglected and decaying apartments far superseded the cost of renting brand new apartments in the cities more costly northern neighborhoods.

-

III The Refugees: A Timeline

The influx of African refugees to Israel was first precipitated by the startlingly violent beating and murder of 28 Sudanese nationals at the hands of Egyptian police in 2006 (New York Times, 2006). At the time, there was no fence on the Egyptian-Israeli border, and with the help of Bedouin smugglers, many African’s fleeing hardship began to see Israel as a promised land – one which provided decent opportunities for a better life.

By 2011 more and more refugees continued to pour into the city. They began to open business – internet cafés, bars, injira restaurants, and salons, increasingly intergrating into the local labor force. As a source of cheap labor, they could be seen doing a variety of urban maintenance work, as well working in kitchens and a variety of other restaurants. At this time, residents of Neve Sha’anan began to mobilize and speak out against these ‘foreigners’ who they felt were taking over their neighborhood. Rather then directing their anger at the municipality and government – who’s policies – or lack thereof – had forced these vulnerable groups to band together in an already under serviced neighborhood. The resident’s frustration increasingly turned against the refugees.

In 2011 local right wing Israeli activists were given a plot of land in Neve Sha’anan, under the aegis of creating a garden ‘for Israelis.’ This was done without any official tenders, agreements, or announcements, and with the municipality’s tacit support, a group of young gentrifying ideologues began knocking on doors, seeking out the neighborhood’s mostly alienated and and elderly population of local Israeli’s to join the new urban garden. Foreign workers and refugees were not invited to participate, and although the founders insisted that integration takes time, there has since been no programming aimed at using the space to foster co-existance within the community. The garden is surround by tall apartment buildings where African and Filipino residents peer out at the communal gatherings and fresh produce they are forbidden from enjoying.

I spent many afternoons in the garden with the local members, and beneath their heatedly racist rhetoric, there is real suffering; one 80 year old woman told me that she was the only Israeli in her building. In the beginning she would beseech her migrant neighbors to not leave garbage in the building, but over time they grew aggressive towards her, and she feared speaking up. Under the same premise of bringing new life to this dilapidated area, local activists mobilized to create a festival called ‘Nite Lites’ which features video art installations, food carts and other programming over Christmas. Tens of thousands of shekels have been poured into these events over the last three years.

-

VI The Sinai Torture Houses

The plight of the refugees is further compounded by the emergence of kidnappings perpetrated by Bedouin communities in Israel and Egypt, who hold African migrants in torture houses in the Sinai desert, charging ransom for repatriation. Women are repeatedly beaten and raped, and are given cell phones to notify their families. The price for their lives now exceeds 50,000 dollars. An investigative report by investigative journalist Ilana Dayan follows the ransom payment in Tel-Aviv, yet police have been totally negligent in intercepting these drops.

Once the refugees are freed, they have to make the dangerous journey to the Israeli border, where the Egyptian police shoot to kill, and the Israel jail’s them upon entry. This phenomenon is closely documented in ‘Sound of Torture’, a documentary by Keren Shayo which closely follows Meron Estefanos, a Swedish-Eritrean radio host, who broadcasts a weekly radio program on the situation of the Eritrean hostages held in Sinai. Estefanos fields live calls from hostages and their relatives hoping to facilitate their release. The film follows Meron to Israel and the Sinai Desert, where she meets face to face with those who reached out from the torture houses, exposing the horrific reality of the torture camps and of the many victims they have claimed.

The film shows shots of massive unmarked graves, where those who don’t make it across the border are buried in unmarked plots. As I exited the film, a friend showed me a recent post from Netanyahu’s instagram – proudly celebrating the ‘departure’ of over 5,800 ‘infiltrators’, whose lives had been made so miserable that they would choose the gamble their lives rather then live in the open air prison that life in Israel had become for them.

-

V The Rise of The Right in Israel

The public humiliation of the refugee population continued, with several notable events taking place. In May of 2012 massive demonstrations took place in Tel-Aviv’s Hatikva neighborhood. A young MK named Ayelet Shaked made a name for herself with her sharp criticism of the immigrant community.

On May 23rd 2012 a massive protest attended by political figures including Danny Danon and MK Miri Regev took place in Neve Sha’anan – where crowds attacked African passersby, lit garbage cans on fire, smashed car windows, and destroying the storefronts of African owned businesses, earning the demonstration the title ‘Kritallnacht in Tel-Aviv’ – a reference to the dark days of 1938 in Germany where the windows of Jewish owned business were smashed. According to an article on rt.com, “The crowd cried “The people want the Sudanese deported” and “Infiltrators get out of our home.”

This attack was coordinated with no legal protocols, by which the Tel Aviv Municipality stopped issuing business licenses to Eritrian citizens, even for those who hold Israeli work visas. “The city explained the rejections on the pretext that it only grants business licenses to people holding work visas, when the duration of these visas extends to the entire length of the business permit’s duration. Tel Aviv’s business licenses are given for one year, whereas Eritrean citizens need to renew their visas every four months, effectively baring Eritreans from obtaining business licenses,” (Haaretz, 2013).

By early 2013 the authorities, The Refugees were finally able to formally seek recognition as refugees, but hardly any of the cases heard were accepted. According to Lisa Anteby-Yemini, in her article 03 Anteby-clean, while other global-north countries accept an average of 87% of asylum requests from Eritrean asylum-seekers, in Israel there have only been seven requests granted by the third quarter of 2016. Similarly, while the rest of the world grants an average of 63% of requests for asylum from refugees from Sudan, only one Sudanese national received refugee status in Israel:

“Recently, PIBA has begun to reject requests for asylum out-of-hand on the grounds that they were ‘delayed’, even though for years they have denied Eritreans and Sudanese the opportunity to request asylum, never informed them of a change in this policy towards them, and certainly never told them of the existence of a deadline for submitting requests. The conclusion from all this is clear: the Israeli immigration system is built so that no requests will be granted, by applying stringent criteria and restrictions that are unacceptable in the rest of the world.”

Around the same time, the municipality of Tel-Aviv began issuing permits to ‘Israeli’ students willing to move to Neve Shaanan and the Hatikva neighborhood (Haaretz, 2013), Dan Peer among other activists began a campaign to rid the neighborhood of the refugee population through their own political organization ‘Darom Ha’ir’ – ‘The South of the City’, blaming the refugees for the downtrodden state of the neighborhood. Rather then directing their anger towards governmental policies which forced the refugees to band together under conditions which would wreak havoc on the infrastructure of any city. The truth is that without a legal status to protect them, they are obligated to depend on their own networks, and are unable to disperse throughout the country. Furthermore, the residents of these neglected quarters would do better to direct their anger towards the government and municipality.

What is even more disconcerting, is that the ‘Darom Hair’ masquerades as a ‘left leaning’ organization, and is made up of secular educated young people, who disguise their hatred under a smokescreen of concern for the dilapidated state of the neighborhood. Beyond the fact that this area had been totally neglected and poverty stricken for years prior to the arrival of the refugees, the neglect they rail against is also the very factor which enabled all of these young people to find affordable housing within the area. Furthermore, I can attest to the fact that, from my experience, that the most dangerous parts of the neighborhood are connected to largely Eastern European prostitution rings, drug dealers, and mafia, which have little to do with the African Migrants.

While the mood continued to sour against the refugees, in 2013 Israel completed construction on a security fence on the Israeli/Egyptian border, which has resulted in the almost complete termination of the refugee influx into Israel. The public’s wrath for this group, however, has only intensified.

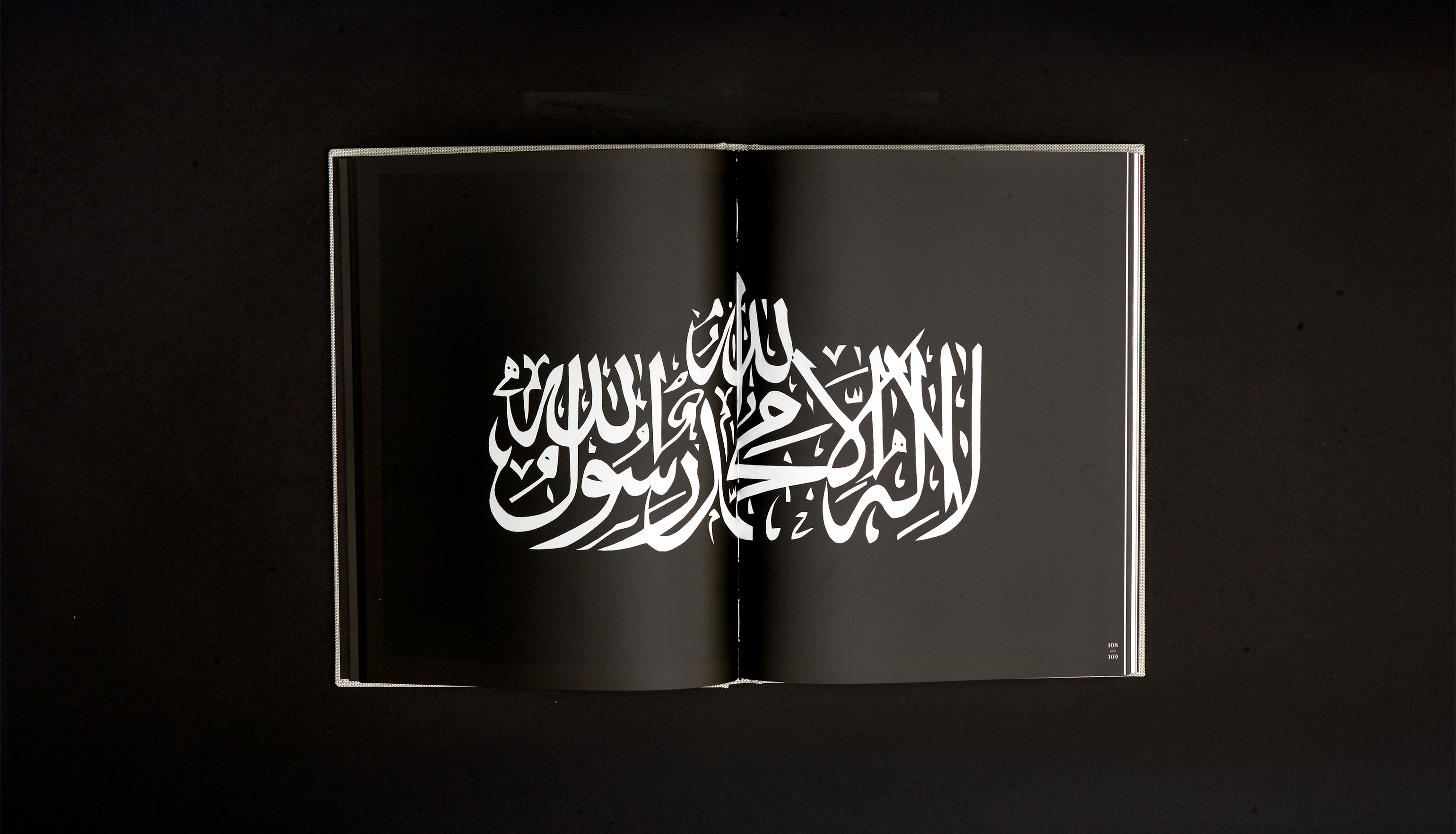

The term ‘infiltrators’ is derived from a law passed in 1954, titled The prevention of Infiltration Law, which gave the state the legal rights to criminally pursue anyone who illegally enters Israel. Initially the ‘infiltrators’ were deigned as residents of the Arab countries surrounding Israel, or Palestinians residing in the West Bank or Gaza Strip. In 2012 the government amended the infiltration law to include the thousands of African refugees who began to pour through the ‘open’ Egyptian border, transforming these populations from ‘refugees seeking asylum’ into criminals in the eyes of the State.

The amended version of the law allows for the detention of migrants who enter the country illegally for up to a year without trial and allows the state to hold those already in Israel indefinitely in the open detention facility. The amendment replaced previous legislation that allowed for detention without trial for up to three years.

The government opened ‘The Holot Detention Center’, Hebrew for sands, the remote new facility is open by day and locked at night. But detainees have to be present for roll call three times a day, a provision meant to prevent them from working outside.

Israel’s Supreme Court overturned that law in September, ruling that it violated principles of human dignity and freedom. Local human rights groups have already petitioned the Supreme Court against the new measures.

In 2015, an immigrant from Eritrea, Habtom Zarhum, was beaten to death by a mob after being misidentified as an assailant in a terrorist attack at the Beersheva bus station.[76]

This past Spring Israel’s high court outlawed The Holot detention center, where African migrants have held without trial and ordered some 2,000 inmates there to be released over the next three months.

While the future is still ambiguous, the refugees future is still uncertain. Open a newspaper and daily there are articles filled with stories of refugees being segregated into seperate schools, and subject to an ever changing series of rules designed to make their lives so untenable in Israel they would rather choose the dangers of exile.

Venice Biennale For Architecture, Artis, The Jack Shainman Gallery, Printed Matter Art Book Fair, Alon Segev Gallery, Chelouche Gallery, Braverman Gallery, UMapped.