-

Notes On Decapitation by Frank Heath

Late one Christmas Eve in the 1950s my great aunt and uncle were killed in a horrific car crash. Throughout my childhood in the 80s I noticed that anytime the accident came up in conversation it was still very difficult for my grandma to acknowledge. It was understandable considering the tragic loss, but I sensed there was something dark and secretive about this event for her. Clearly it wasn’t something we should talk or ask about. It wasn’t until I was an adult, late one night, very reticent, my mother revealed that in the crash they were both decapitated.

The separation of a head from its body cannot be survived. Fingers, toes, an arm, or even multiple limbs can be successfully amputated, but never a complete head.

Decapitations may occur for a number of reasons: execution (French Revolution), sacrifice (ancient Maya), ritual murder (Jeffrey Dahmer), posthumously for preservation or study (Mütter Museum), as trophy (heads on pikes, taxidermied animals), terrorism (hostage beheading videos), or by accident (my great aunt and uncle [allegedly]).

Ancient statues are often missing their heads or limbs. Some were made with detachable or swappable heads. Others lost their crown during a raid, uprising, or hostile take-over. Most statues that glorified an overthrown leader were defiled in this manner. In other cases, the neck or limb joints, points of structural weakness, are where a break would naturally occur.

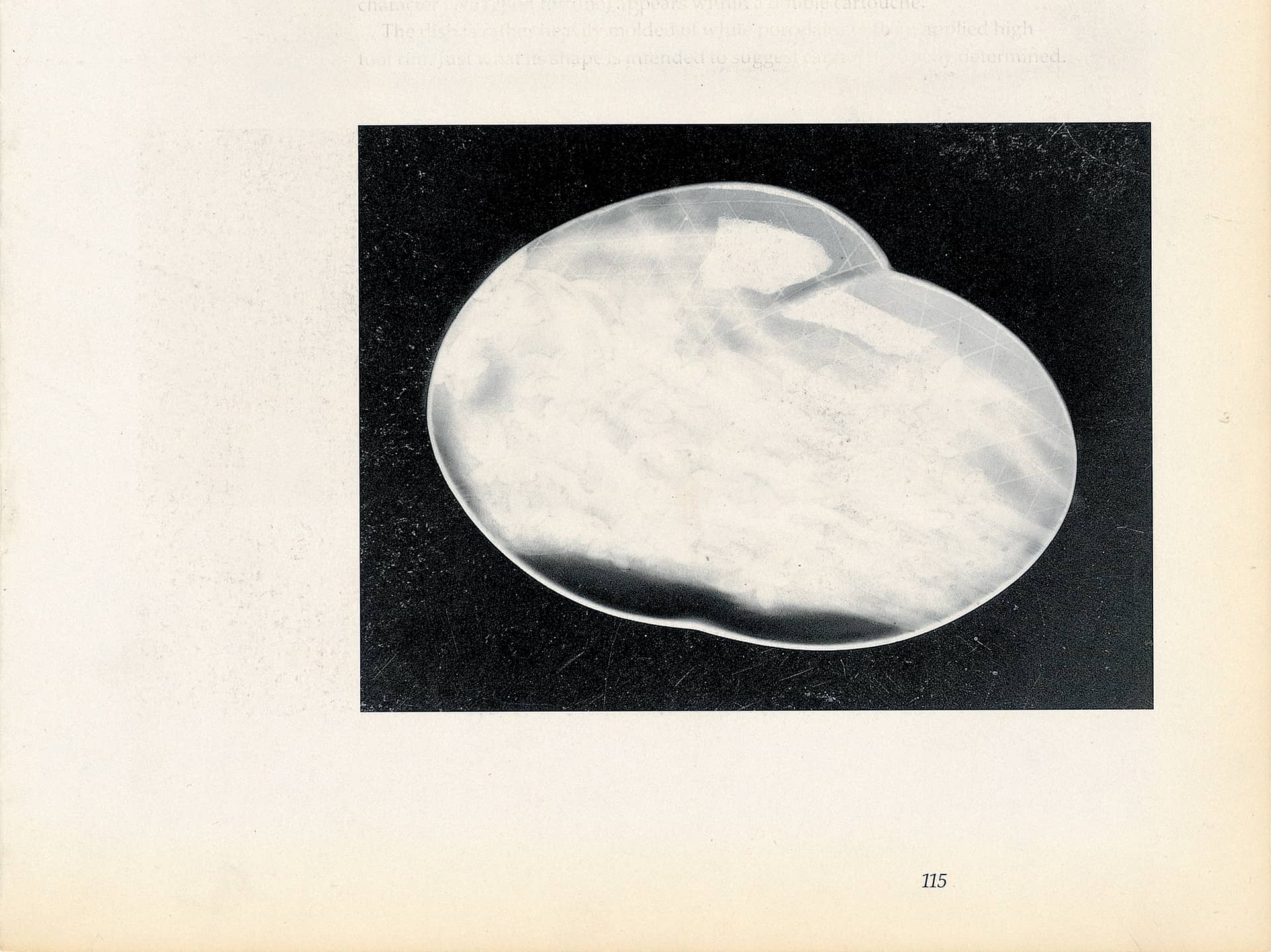

Shortly before my grandma died, she revealed more specifics: The heads of my great aunt and uncle became detached and were thrown from the vehicle. Apparently, they smashed through the windshield, launched into the freezing air, transformed into a hot molten glass, and rolled across the pavement fusing into one. The volume of one head, made of glass, mirrored black volcanic rock. Their two distorted, yet recognizable, faces twisted across its craggy surface. None of the organic tissues or bone from their human heads could be found or accounted for, and no one could explain it.

During the process of making cast sculptures, the head is sometimes severed from the model, breaking the shape into parts that will easily release from the mold. The head of say, the statue of an owl might be unceremoniously cut off to be cast separately. This can be a simple way to eliminate an undercut and prevent the statue from getting stuck inside its mother shell. The original copy must be destroyed for the purpose of making it reproducible.

One pervasive urban legend claims that the body of Walt Disney (or possibly only his severed head) was cryogenically frozen after his death in 1966. Walt’s head remains (allegedly) on ice until the day when technology may exist to reanimate him back to life. Frozen, in hope that humans will eventually be able to reattach the head to a new healthy body or crack the code of our brains, transforming them into accessible and transferable hard drives which contain our memories and consciousness.

In New York City, heads (or other loose body parts) found in the wild are sent to Hart Island. The small uninhabited island in the East River serves as the city’s potter’s field where the bodies and detached parts of approx. one million unidentified and poor are interred. The cemetery is operated by inmates from a nearby prison who bury the dead in simple pine box coffins stacked in mass graves.

The rest of the family simply didn’t believe it. They elected to believe that the heads were somehow missing or destroyed. So, the police gave the glass object to my grandparents in an evidence bag and advised them to keep quiet. They wrapped it in a quilt and kept it in a trunk in the basement. Grandma said that she would go downstairs and take it out, unfold its blanket on the floor, and sit next to it sometimes. She was afraid, but nothing ever happened. It never spoke to her and there seemed to be no curse, no mysterious incidents, no further decapitations. It was calming for her to stare into the glass eyes, but silently, it haunted the house. What could they do with it? They couldn’t just throw it away, it was her sister’s head. Her brother-in-law’s as well. Grandpa tried to pay a groundskeeper to bury it in the cemetery plot with its bodies, but that backfired, he went all over town talking about it. Eventually, they decided to bury it near the cement birdbath in the backyard, and promised to never speak of it again.

In a televised interview from prison (Dateline NBC, 1994) the serial killer Jeffrey Dhamer and his father discussed the murders for the first time together. In the most chilling anecdote from the broadcast, they recall an incident where, in the living room of his apartment Jeffrey refused to show the contents of a suspicious box to his father. Tense and agitated, Jeffrey wouldn’t back down. After a brief argument, his father gave in and left without finding out what was inside. Had its contents (the mummified head and genitals of one of his victims) been revealed at that time it may have saved the lives of numerous subsequent victims.

Every few years when I make a trip home, my parents like to drive us around town and show me what has changed. Mostly it’s more empty storefronts and fast-food chains. We usually make a stop at my grandparents’ old house to have a look. The people who live in it now don’t take care of it. Paint is peeling everywhere, screens around the porch are shredded, and my grandpa’s once immaculate lawn is completely dead and brown, except for a small patch near the birdbath.

France staged its final execution using the guillotine in 1977.

Frank Heath, 01/22, NYC.

-

The Big Sleep, The Little Death or Hi, Shahar by Tchelet Ram

A couple of days ago I saw a black cat. I thought of you. It was noble yet awkward, its yellow eyes followed me quizzically as I tied my bike to a pole. Yesterday I saw another black cat. It was dead. I thought of you.

When you spend time in silence, it is hard to start talking again. The jaw muscles are stiff, and the soft mewing the throat manages to produce can hardly make a syllable, let alone words. Instead, I imagine a conversation – and since it is the figment of my imagination, it can be free of sound. And so, the speechless objects become the speakers, and they will recount how one thing stands next to another, how it assimilates into another, how it becomes the other. The silence will become a material that will overflow and congeal into a shell for nothingness, encasing emptiness. And it will shield the “nothingness” inside it as if it were a material by itself. “Nothingness” that can fall down and break. A glass balloon, an empty mold.

But, while we were actually talking, I was able to catch a glimpse of your logic through the veil of thick smoke that started to fill the room: Imaginary axioms about the law of gravitation, about the temporal dimension, about the life of a sculpture, and its “mortal” nature. Just as you sculpt, in your measured words you form a “mold” that only leaves hints to the thought’s original shape. You also imagine a conversation. And then, in that encounter, your speech loosened and you said: “I burry it,” or, “it’s sleeping,” or “it wants to be.” And the logic crumbles and the simple speech that tries to capture the sculptures’ consciousness ends up capturing your own; your wish that it will die, sleep, be a thing in the world. And it is sculpted and drawn. The sculptures are heavy, rational, rooted in past actions and guided by predefined rules. The drawings are free, they appear on the surface, although they lack an actual plot, they are full of figures, beginnings, and ends.

When you invited me to the studio, you spread a purple yoga mat on the floor and told me to lie down. I was wearing a blue shirt and jeans. I had long hair back then. I laid on my stomach and you covered me with a yellow plastic sheet. You rolled me a cigarette and put down an ashtray and a glass of water beside me. You wrapped my legs with bandages. When you finished, you shoved the cigarette in my mouth, crossed my hands behind my back and took a photo. I was not the only one but it was special for me. You buried me.

These merciful tombs, rigid shrouds for the sculptures of others, for people’s legs, for plastic plants. The image remains inside, like a heart out of sight. The sculptures, animals, and life expand through space, intensifying. Giving back the body its abstract form. Like a frog that grows into a tadpole.

The past is once again the present; through them, history is experienced as static, as a series of recurring questions: How do you make a sculpture? What is a sculpture? How can it still speak? When I was in Spain, I visited the Cave of El Castillo. Inside the cave, on the rocks, imprinted hands seem to delineate the path to its depths. They have been there for forty thousand years. The guide was tired and tiring, of course we couldn’t come close, touch or smell. And he spoke at length about preparing the cave for visitors and how vulnerable the cave paintings are. And I kept thinking: How vulnerable can they be, they are still here. One can imagine how over the years the hand print became the signet ring or a personal signature on a bank form. And how over time these will also lose their ability to point back to an individual subject. But perhaps they are also the graffiti “I was here” sprayed on the wall of a tunnel, which under my gaze dissolves the first person until it also says “you are here” and “they’ll be here.”

And among all the hands there was one with a reddish-brown halo and a missing finger. It was painted by laying a hand on the wall and blowing pigment on it. A negative, empty, ideal hand, the hands of the whole of mankind. And it is also the hand that presses the clay in your sculptures, time and time again. The hand of the figure, your hand, maybe a place to hold the sculpture.

Your sculptures dream, unable to wake up – I think about that when I wake up in the morning and forget my dreams. In their sleep, they ignore anything that is not them. They imagine it in fragments. They dream of the ground beneath them, of the tree above them, of the hands that will move them from place to place. They are in all the places they have been to and in the ones they will be. But they do not dream of us, the people who move them around and then let them be, and fill them with reason. In their sleep they hold time.

In our last meeting you said that in each one there must be two. The scale is faithful to reality; a glass head will be the size of a human head but will feature two heads, and perhaps a bird too. Siamese twins; Brahma, the Indian god that has eyes in his back, so that he will always be able to look at his beloved; the two-faced god Janus – the god of portals who intertwines youth and old age, primitivism and civilization. Compressing an entire world into a human body. Into a head. It’s all in your head.

My head is heavy. At the end of the story, I found myself between the tombs and the heads.

I’ll see you soon,

Tchelet

-

Blunt Liver by Hila Cohen Schneiderman

Adam and his helpmate were sitting and weeping and mourning for him, and they did not know what to do (with Abel), for they were unaccustomed to burial. A raven (came), one of its fellow birds was dead (at its side). (The raven) said: I will teach this man what to do. It took its fellow and dug in the earth, hid it and buried it before them. Adam said: Like this raven will I act. He took the corpse of Abel and dug in the earth and buried it. The Holy One, blessed be He, gave a good reward to the ravens in this world.1

(Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer 21)

I tried to write about Shahar Yahalom’s sculptures during the day. I failed. I wrote of them at night. I am using the word “sculptures,” even though there are also drawings and monotypes, since the sculptural logic pulsates through these as well, forming a condensed space where the images are compressed together as in a dream, manifested in and through the material. The sculptures are drawn and the drawings are sculptured. Images and figures embedded in the material, subject to its inner boundaries, their heads bowed before the law imposed on them. Yahalom is the ruler of the maze while simultaneously trying to find her way through it; the legislator and the one who follows the law, enumerated into pedantic actions whose logic remains obscure, internal and at the same time completely visible to the beholder.

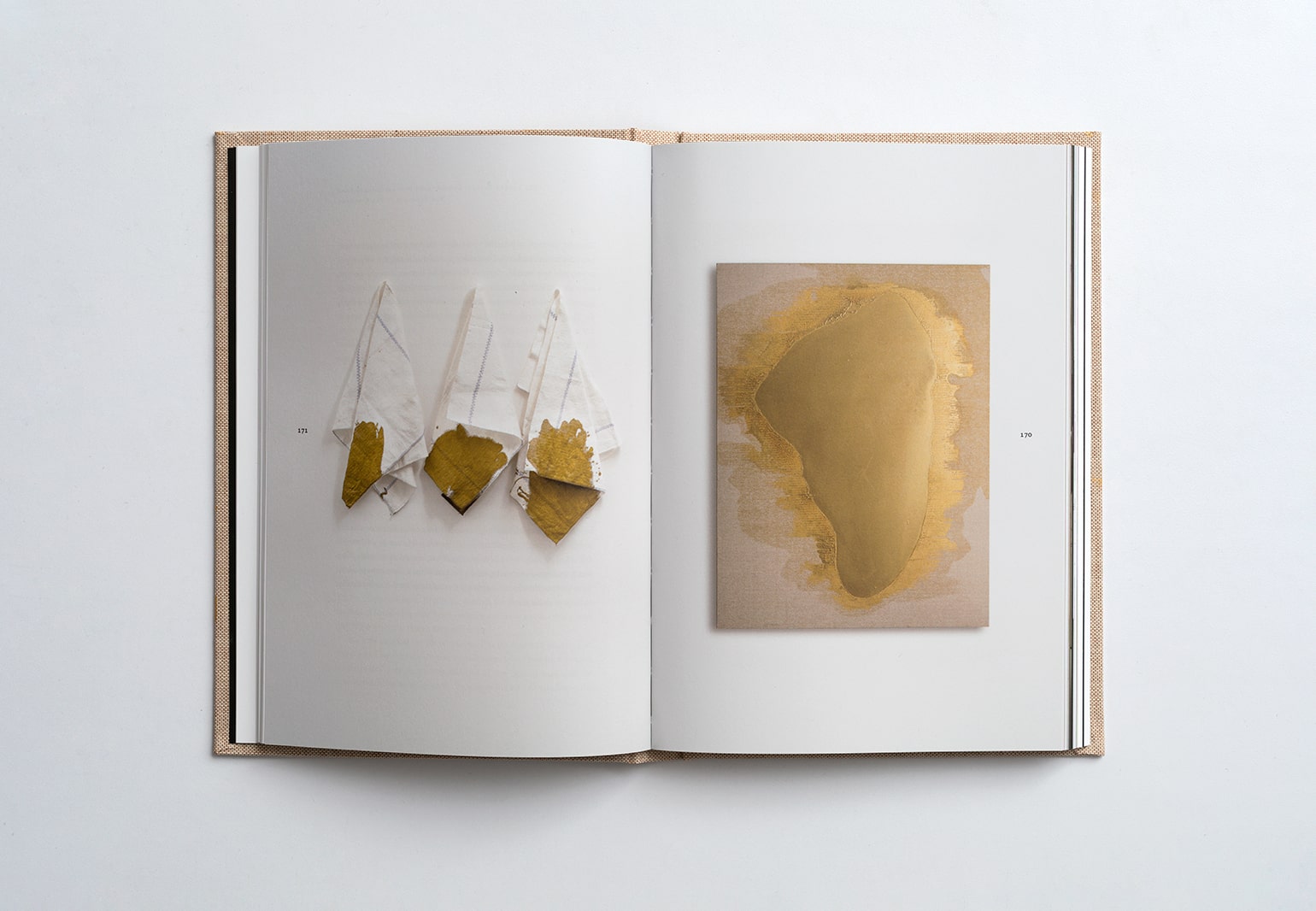

In Yahalom’s works, the line is not used only to convey a state of mind or capture an image on paper, but goes on to pierce through the material, making room for the image inside it. In the glass works, for instance, the line becomes inextricable from the glass itself. Line and matter become one to the point that sometimes the line is invisible and only reveals itself when the light hits the sculpture, exposing the surface and salvaging the image from its depths. Light infiltrates the sculpture, penetrating the transparent armor and trapped in it, like a moon that reflects the light of the sun. Indeed, in Yahalom’s works it is difficult to distinguish the inside from the outside, mother from son, the fragmented from the whole, wakefulness from slumber, and life from death. The child’s head is placed on the mother’s head, as if it were another organ of her body, and the glass fragments are fused together. Looking at them, one can see the inner space that remains empty, trapping the air inside.

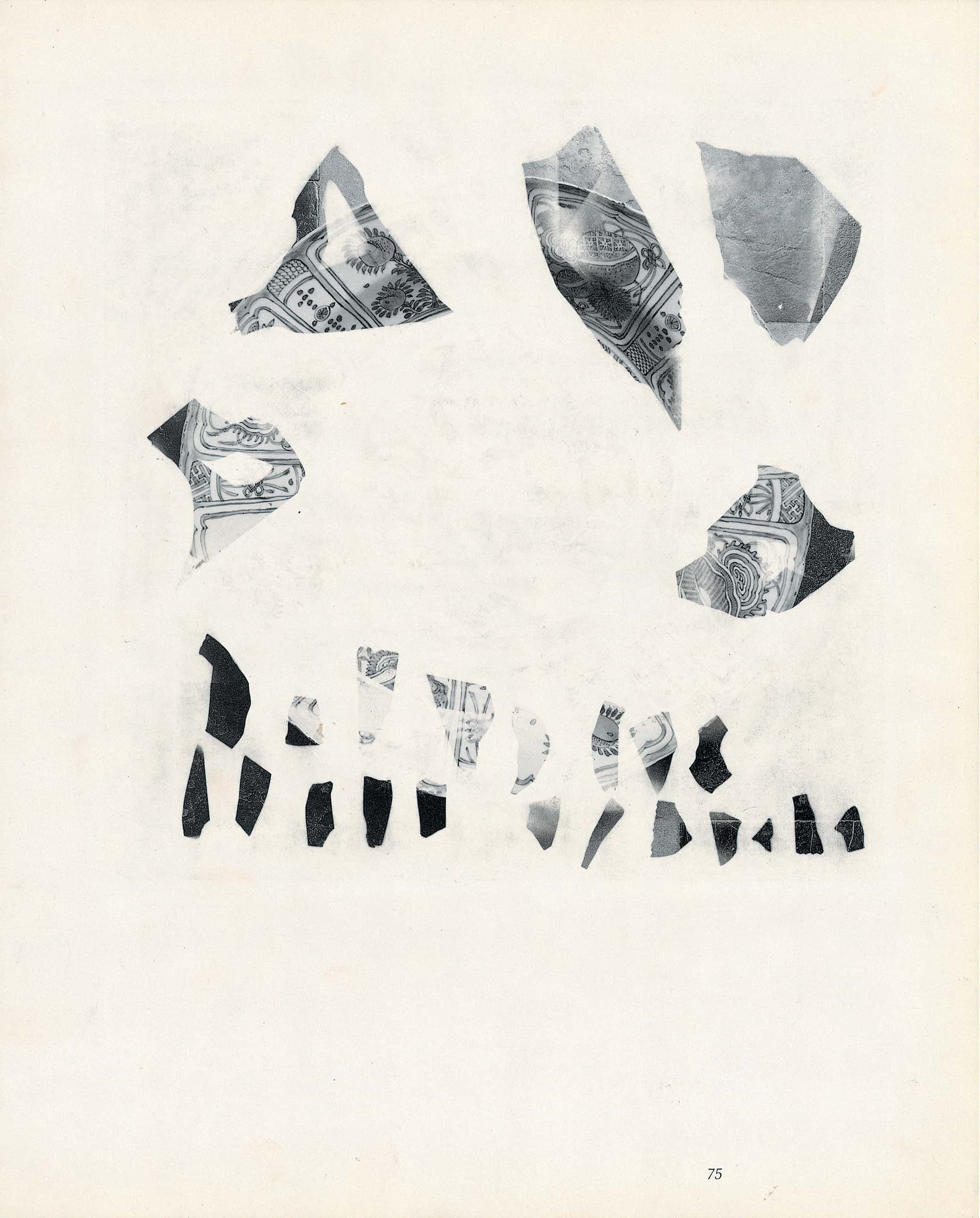

Yahalom’s works are observation spaces for the delicate and deceptive transitions between movement and stillness, between the living and the dead. For her, death is not a static and absolute thing, it is not one dimensional or one directional, but an essence that one must approach in the most physical way, by following the procedures of the undertaker: the one who is with the deceased, washes the dead body, shrouding it, building a box and a mold that trace its outline or places it in the ground. At times it seems that Yahalom is a descendant from a long line of undertakers. But while ancient burial practices (mummification, burial with grave goods, preservation of internal organs and so on) were devised to allow the dead to continue the passage to the afterlife, with the act of molding Yahalom engages in the manifestation of the departed as a sculpture. One might say that she is more interested in the tomb than in whatever is entombed – be it a wreath, shoes, a donkey, or a white owl, her fascination lies with the sculptural space. Building a mold is an act of taking care, a thoughtful caring action based on profound respect and careful observation of the object, whose distinctive shape can be learned and internalized by encasing it. Through the shaping of a mold, the body or object is removed from the equation, and the entombed becomes a negative space – a material memory, a home for the space of the absent body. The tomb-mold is a material and a silent representative of everything that remains inaccessible to us.

Yahalom’s tombs are built around sculptures that represent nature – a jackal, a headless white owl, flowers, a rock; they capture the anima of the inanimate as spirit embedded, accumulated, or trapped in matter. However, Yahalom is not a “spiritual” artist, but an artist “of-spirit.” She does not see the world of spirit as a higher realm that overshadows the physical and material life, but rather puts the inanimate matter at the core of her actions. An artist of spirit – or an artist in-spirit if you will – lives within the laws of nature, as part of nature – with the gust of wind, animals, trees, rocks, tombstones – all of which have a soul. The tomb, like the sculpture, concerns eternity, which requires a perspective distance from the now. One might say that unlike contemporary art, which relinquished the possibility of eternity in favor of contact with the present, Yahalom looks for ancient values of action and approaches them from the present.

Yahalom has a relationship with the dead, but no less so with the living. Her sculptures are the outcome of collaborations with artists who work in disciplines that lie beyond her expertise. In many respects, even before she decides what she wants to sculpt, she chooses whom she wants to work with – usually joining forces with artists who operate in very esoteric areas or specialize in a highly specific activity. For her, this is as an opportunity to expand her sculptural language, and to feed the actions of her collaborators, so that a space of mutual learning takes shape, a tangle of interactions. The glass heads, for instance, started from her desire to work with glassblowers. Accordingly, each glass head encapsulates an internal relationship between at least two figures, drawn together in one head. And so, beyond informing and establishing the circumstances of their making, the relationship also imbues the sculptures themselves. The same is also true of the tombs: First Yahalom will choose the person whose work she wants to entomb, and only then she will choose the sculpture. She then buries the sculpture with plaster, and once it has dried, opens the tomb, exhumes the object, returns it to its owner, seals the tomb, and takes it for herself. For this exhibition, she has collaborated with the sculptor Gil Alon, the artist Eti Levi, the family of the artist Yechiel Shemi, photographer Goni Riskin, musician Aviv Ezra and others.

THE THRESHOLD OF LANGUAGE

The exhibition title, Blunt Liver, carries Yahalom’s fascination into the audial realm. “Blunt” and “liver” are the two images that activate Yahalom in this body of work. Here too, the juxtaposition holds an oxymoronic verbal space: Blunt means straightforward or brusque, as well as rough and dull. But pronounced differently, it could also be read as an indication of life, as the “one who lives.” Furthermore, in Hebrew, the word for liver כּבֵָד) ) doubles as “heavy,” introducing associations of mass and gravitation, the dissonance between the weight of the sculptures and their ethereal appearance. Yahalom does not need the exhibition’s name to act as an elucidating title; all it has to do is place us in the conceptual and mental field from which she operated. The title conjures an experience of a numb individual who lives in a dull stupor and connects to a raw, pulsating organ. It unites the darkest organ in the human body, entrusted with the removal of toxins and the dullness, with the rounded movement that attests that the weapon has lost its sharp edge. A raw, exposed, and blunt existence.

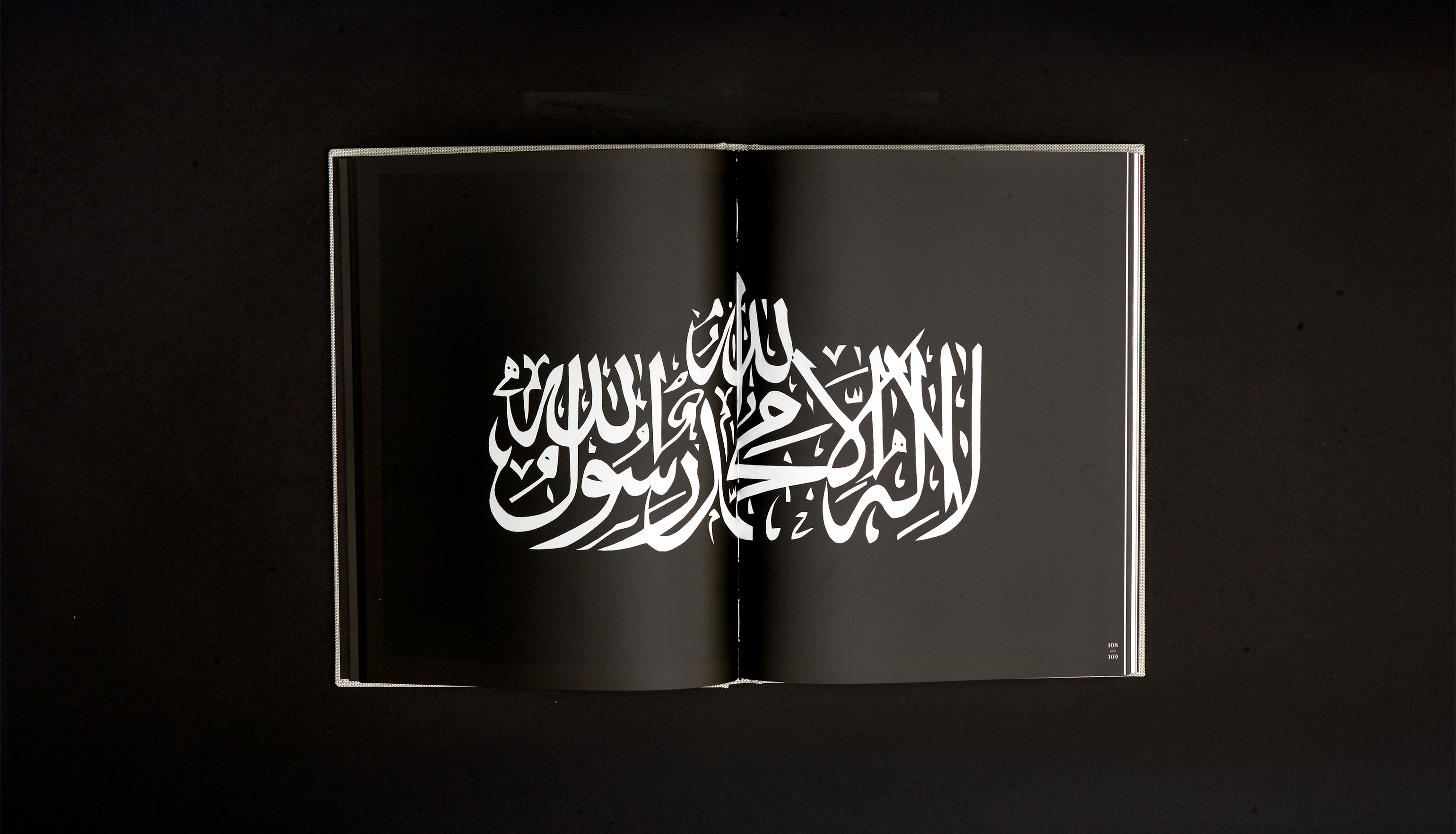

In language, Yahalom is in search for the places where the same sound carries almost opposing meanings – a contronym, which is sometimes referred to as a Janus word or auto-antonym. Like positive and negative, horizontal and vertical, in the attempt to fuse them together, they intersect with one another, creating a foothold from which one can expand ad infinitum and grasp the entire universe. The core of the logic converges into the word’s sound and phonetics – into the movement of the lips that utter the word. For her, the linguistic sense that changes from one language to another is secondary in this system, a mere side effect.

INDEX

Mom Falling off a Cli

The nucleus from which everything emerges is the sound – blunt liver, kehe kaved in Hebrew, the movement of air through the lungs and the oral cavity. Yahalom’s focus is on internal organs. If through her burial practices we conceive the museum as a mausoleum – a sumptuous burial hall for the works of art, in this case, we can also think of it as a “mesenterium” – a sac in the abdominal cavity that carries the internal organs crowded together, pressing against one another while maintaining the body’s essential functions. The shift between inside and outside is also reflected in the relationship between molds and casts: in order to see the cast, you have to remove the mold. They always co-exist but must be separated to be witnessed. To be able to see the inside, one must eliminate the outside. The perspective is in constant flux, unable to choose a side. The attempt to hold on to both ends generated a split into two bodies of work, distinct yet intertwined.

Hila Cohen-Schneiderman

Venice Biennale For Architecture, Artis, The Jack Shainman Gallery, Printed Matter Art Book Fair, Alon Segev Gallery, Chelouche Gallery, Braverman Gallery, UMapped.