-

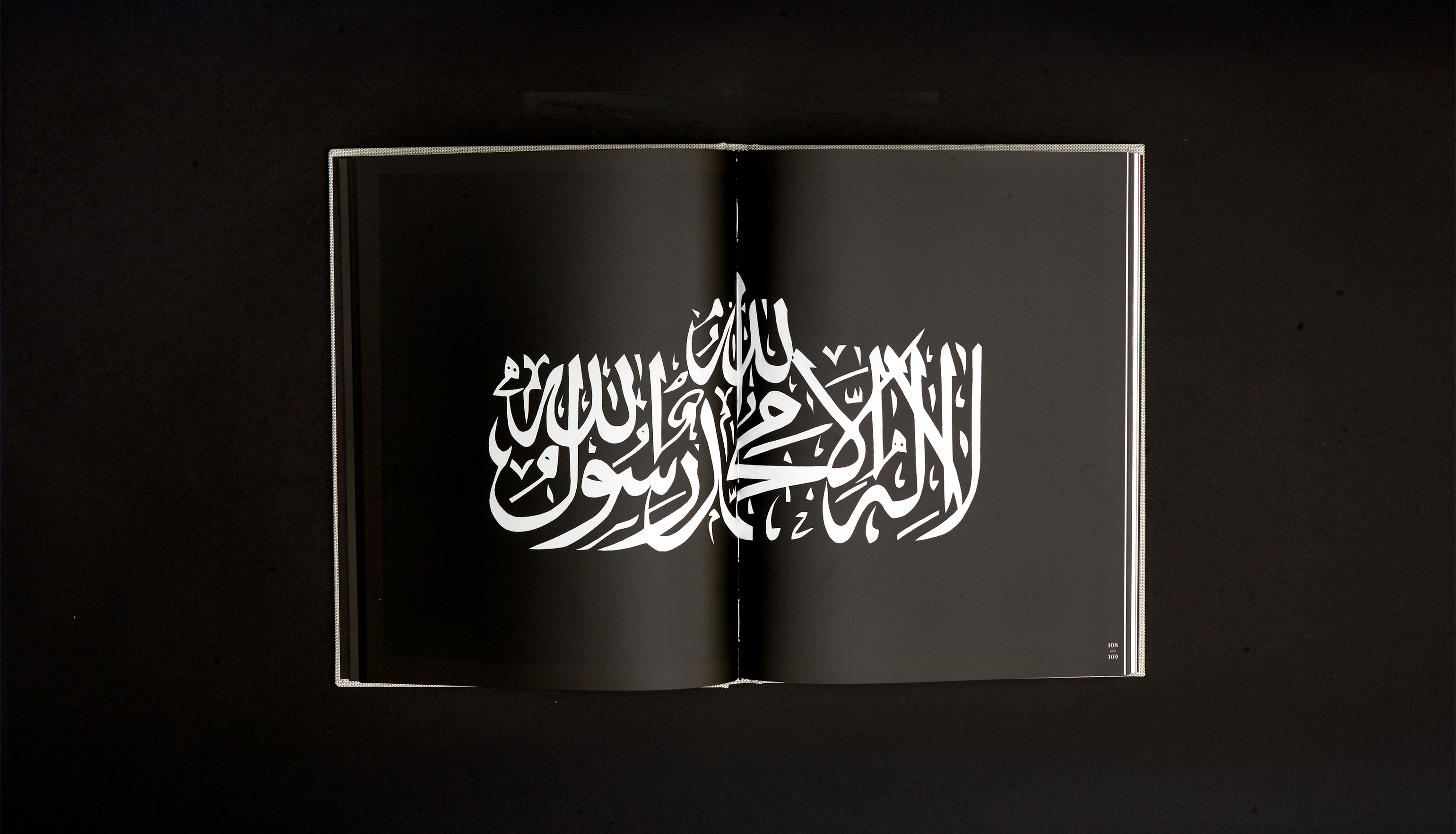

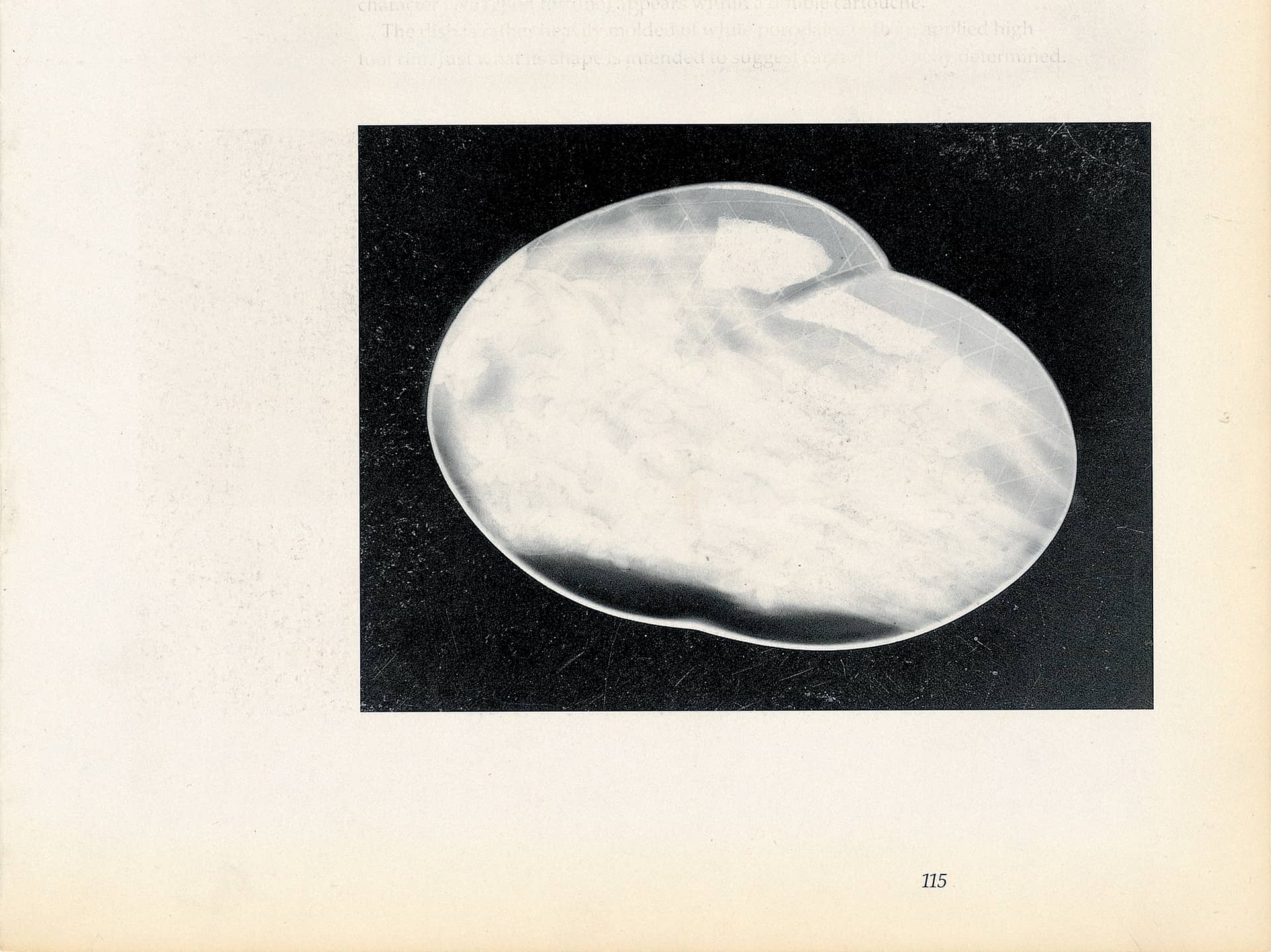

Leor Grady and I met over the cover of my book of poems, Eastern Moon. The Kinneret is for Grady what the moon is for me: a sublime tool, matter and form, a semiotic vessel which contains and draws endless meanings and associations. My book jacket shows Grady’s Gold Kinneret no. 4 – where these ideas unite and pour their contents into one another; The Kinneret becomes moon and the moon becomes Kinneret. A lovemaking-like fusion between those who are usually alone, usually unknown. These influences added additional layers of mystery to the symbol on the book cover: since we each used the other’s sign, the shape seemed amorphic at first, like a Rorschach stain. The gaze requires time to consider what is being signified. When I meditate upon this shape, all sorts of ideas are conjured: heart, map, womb to name a few. Of course, all these ideas are true; symbols are after all ciphers and triggers for various projections. It is within the Kinneret and in the Moon that Grady and I found something of a similar ilk: a sign that has come to represent our selves, and especially our Mizrahi heritage. A sign which projects clearly, yet soundlessly, our cultural experience.

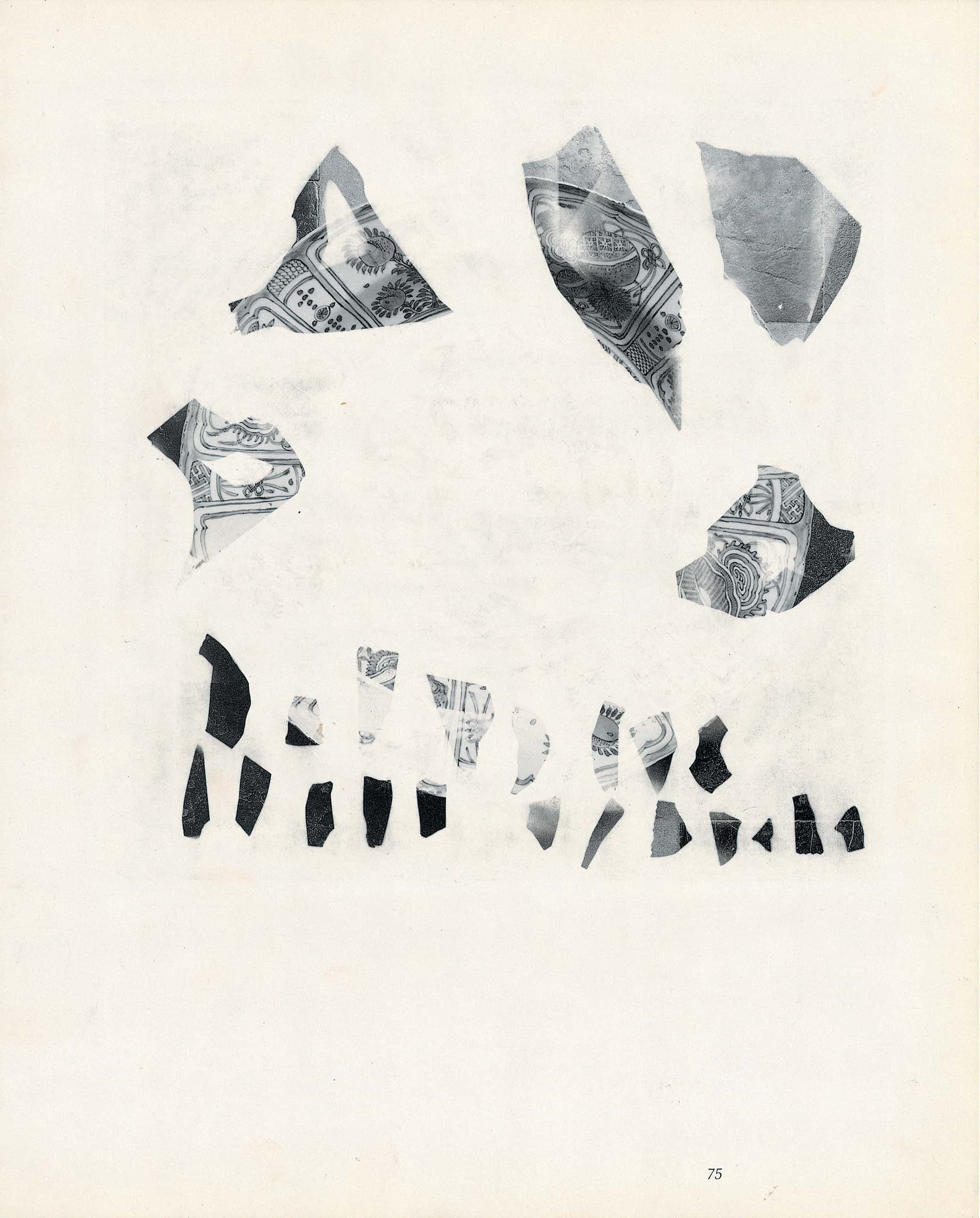

Grady’s Kinneret paintings recall the chalk markings that surround around a body in a crime scene, with the outlines bleeding into the surrounding areas. The body is no longer present, the markings bear prominence only after the body has been removed, and the victim has disappeared, leaving only the remains of victim killed by unnatural causes. Art is an unnatural thing, an artificial intervention, and in the case of Grady’s exhibition and book ‘Natural Worker’, various aesthetic devices are employed to tell the story of a crime long unacknowledged. Grady has a story to tell, yet this story – like the body – is largely forgotten; It is the story of a group of Yemeni pioneers who arrived at The Kinneret before many of the area’s founding pioneers, suffering racial abuse at the hands of the local Ashkenazi settlers, and forcibly resettled in Marmorek by the Zionist governmental agencies. ‘Natural Worker’ speaks for the silent, and the absent, creating obsessive outlines around a crime scene that has long been forgotten. A missing body whose heartbeats continue to echo in and around us.

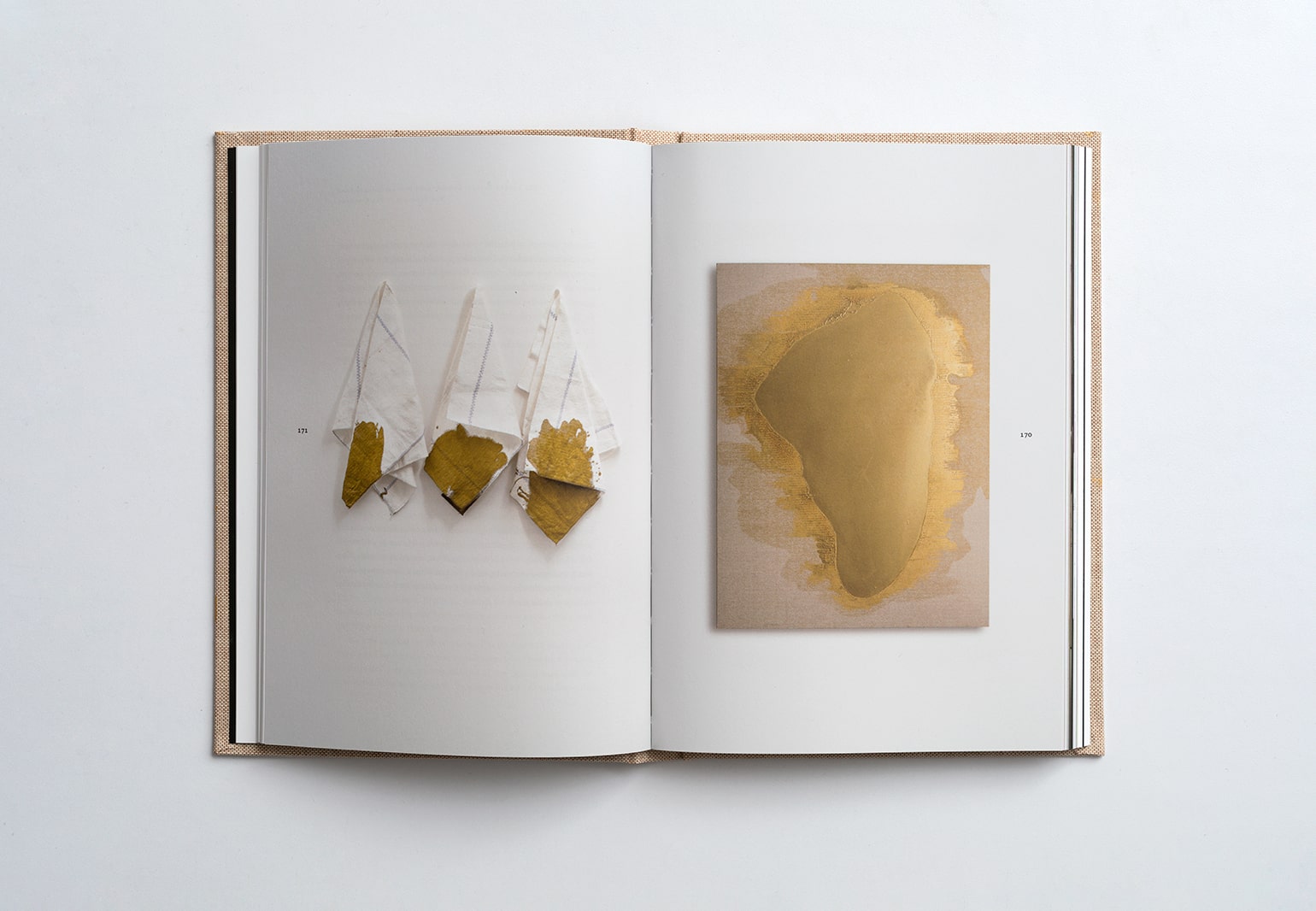

The exhibition unfurls like a mystery novel; Canvases with letters embroidered in gold thread rest along the gallery’s wall like pietas or tombstones. By discovering and threading letters pleaing for mercy, written by the Yemenites of the Kinneret, the artist incorporates historical evidence in order to shed light on a forgotten crime. The works are placed casually, stacked one upon the other, as if they were unwanted, resembling things that no one is interested in. The Natural Worker exhibition was mounted at the same time as the archives regarding the kidnapping of Yemenite and Balkan children by the Israeli government were made public for the first time, alongside the discovery of the letters written by Yemenite settlers in Kiryat Shmona. The paintings are set precisely on the floor, without any support apart from the wall they lean on, without which they would slide and fall. These canvases have no arms wrapped around them, nothing to hold and embrace them. Like our grandparents. Their parents are no longer with them; they experienced the most severe detachment imaginable. At a certain stage in life it is no longer the adult who holds the young but vice versa: It is our generation, the grandchildren, who carry our grandparents and parents in our arms, yet only in a metaphorical sense. We cannot comfort our elders. But we can be their voice.

Like a filmmaker or a journalist retrospectively following a case, Grady brings forth additional findings. Projected on one of the gallery’s walls is a single channel projection where two young Yemenite men dance around each other. The contemporary setting and costumes clash with the traditional movements they recreate; like a pair of detectives who trace the forgotten choreographies of that which is no longer, of the missing body. Grady cast these ‘professional’ dancers to recreate a cultural and historical memory of which they have no part. While this potentially highlights how few there are left to describe this history, I was initially puzzled by this choice. Are the dancers even Yemeni? Murder mysteries usually end with the perpetrators being caught; and in this case there is no question who the criminals are. But by using ‘others’ to appropriate Yemeni heritage in this manner, is this not also a further erasure, one which began with the racism of the Ashkenazi pioneers, and continues with cultural appropriation of Yemeni culture akin to the way that Madonna and Elvis frequently appropriated African American culture for their own gain? Or does the dancers’ identity serve to imitate the theft committed by the Ashkenazi pioneers who erased the traces of their Yemeni counterparts, took their place, appropriated their lands, and killed their dreams of self-determination.

In parallel to Grady’s action, we too are left to reconstruct that which has been lost, either through our imaginations, or the existing testimonials that we have. Our parents and grandparents collectively make up this missing body, this victim, yet we are less sure about what all of this means to our generation, of what ties us to these crimes, and of what makes us continually feel the letting of their blood, and the materiality of that which has passed. I watched visitors interact with the installation, with their gaze cast down toward the works, arms crossed. They approach the art the way mourners might approach an open casket. It was as if they were attending a funeral, not a celebration. Grady illustrated and embroidered the Yemenites’ letters with both beauty and sadness, like a funeral director who beautifies the dead as a final tribute.

This chilling sense of ‘passing’ or ‘memorializing’ is further compounded by the two dimensionality of the works. The video, the paintings, and the embroidered canvases remain within the realm of a surface, collapsing and flattening space. Their two-dimensionality resembles the weight of shadows that hover above the third generation of the Mizrahi struggle. Like a shadow this repressed heritage is both menacing and also weightless – omnipresent – everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The painful load that we carry is also one which many Mizrahim have yet to acknowledge. A silent trauma whose horror rings especially forcefully for this very reason, for its voiceless victims. Grady’s exhibition is like a mouth which opens to speak, to defend, the embrace, the uncovering or resurrection of something that was buried alive. And his task is also ours; a historical responsibility which can only be performed with artistic tools. The resultant oeuvre is a verdict, and what we take with us when we leave his performance is the sentence.

Venice Biennale For Architecture, Artis, The Jack Shainman Gallery, Printed Matter Art Book Fair, Alon Segev Gallery, Chelouche Gallery, Braverman Gallery, UMapped.