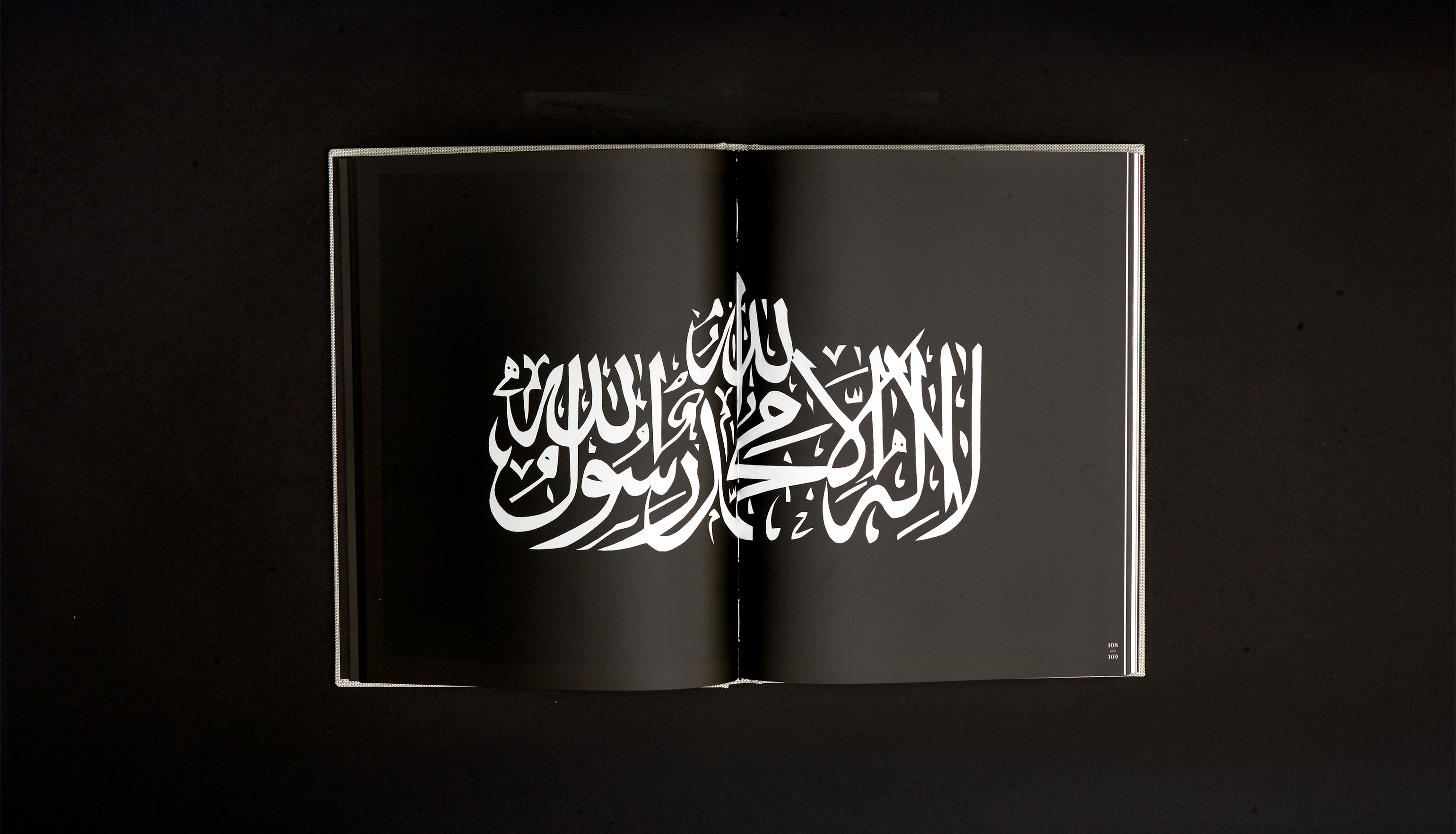

In her project Fajja, which takes its name from a Palestinian Arab village depopulated in 1948, whose land is currently part of Petach Tikva, Keren Benbenisty explores the relationship between typography and topography. The printing press that inspired the project—one of the only two specimen still in existence—was built in 19th-century Germany and imported to Petach Tikva by Jewish settlers in 1932, where it was used to print paper for orchard owners to wrap Jaffa oranges until the 1990s. The Jewish immigrants who settled in Palestine in the early 20th century turned Jaffa oranges—a species cultivated by Palestinian farmers in the mid-19th century—into one of the country’s primary exports. After 1948, the citrus production became established and expanded from Jaffa to other places in the country, among them Petach Tikva, which became a major orange exporter. An emblem of the lost Arab-Palestinian land, Jaffa oranges became one of the quintessential symbols of the nascent State of Israel.

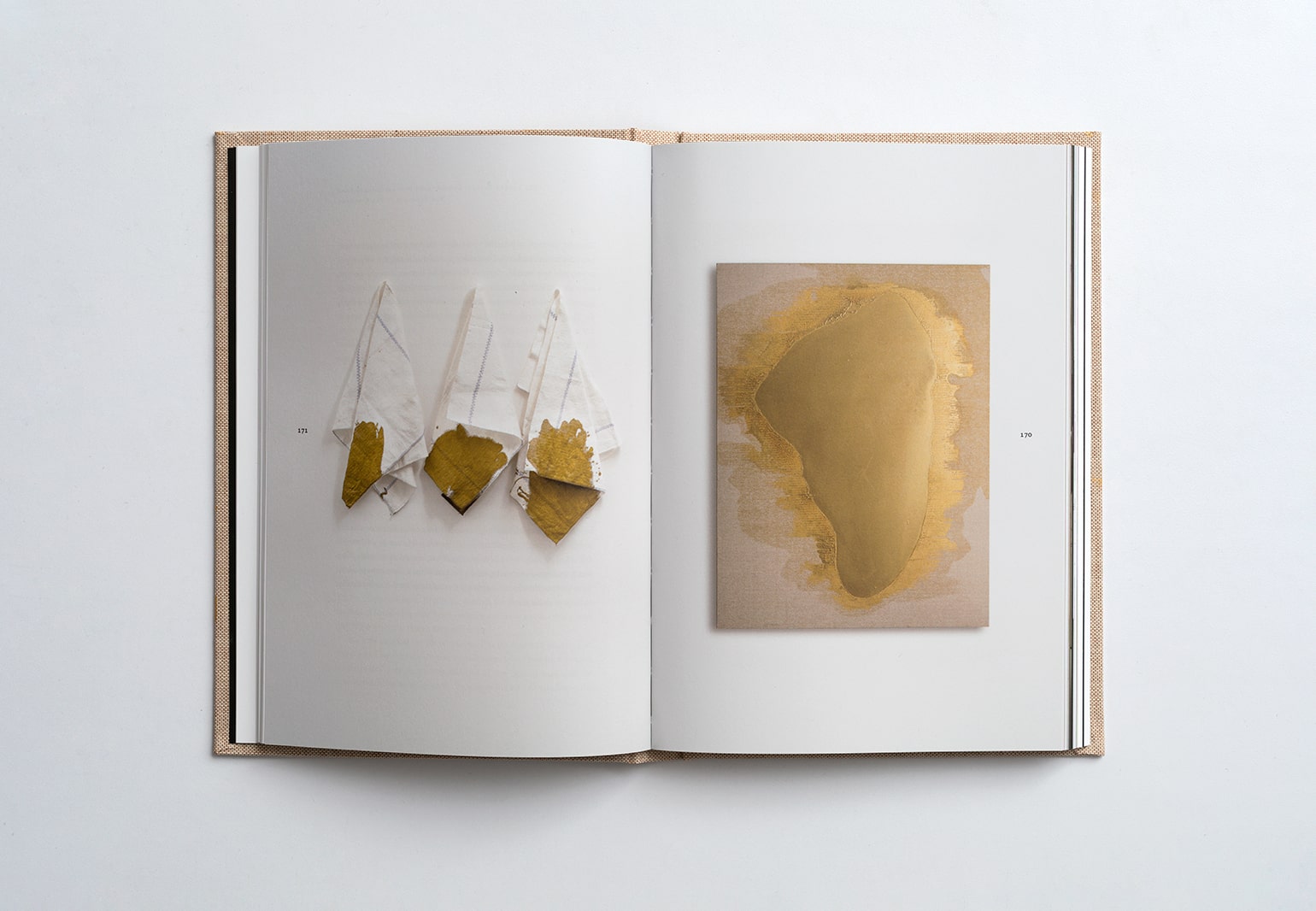

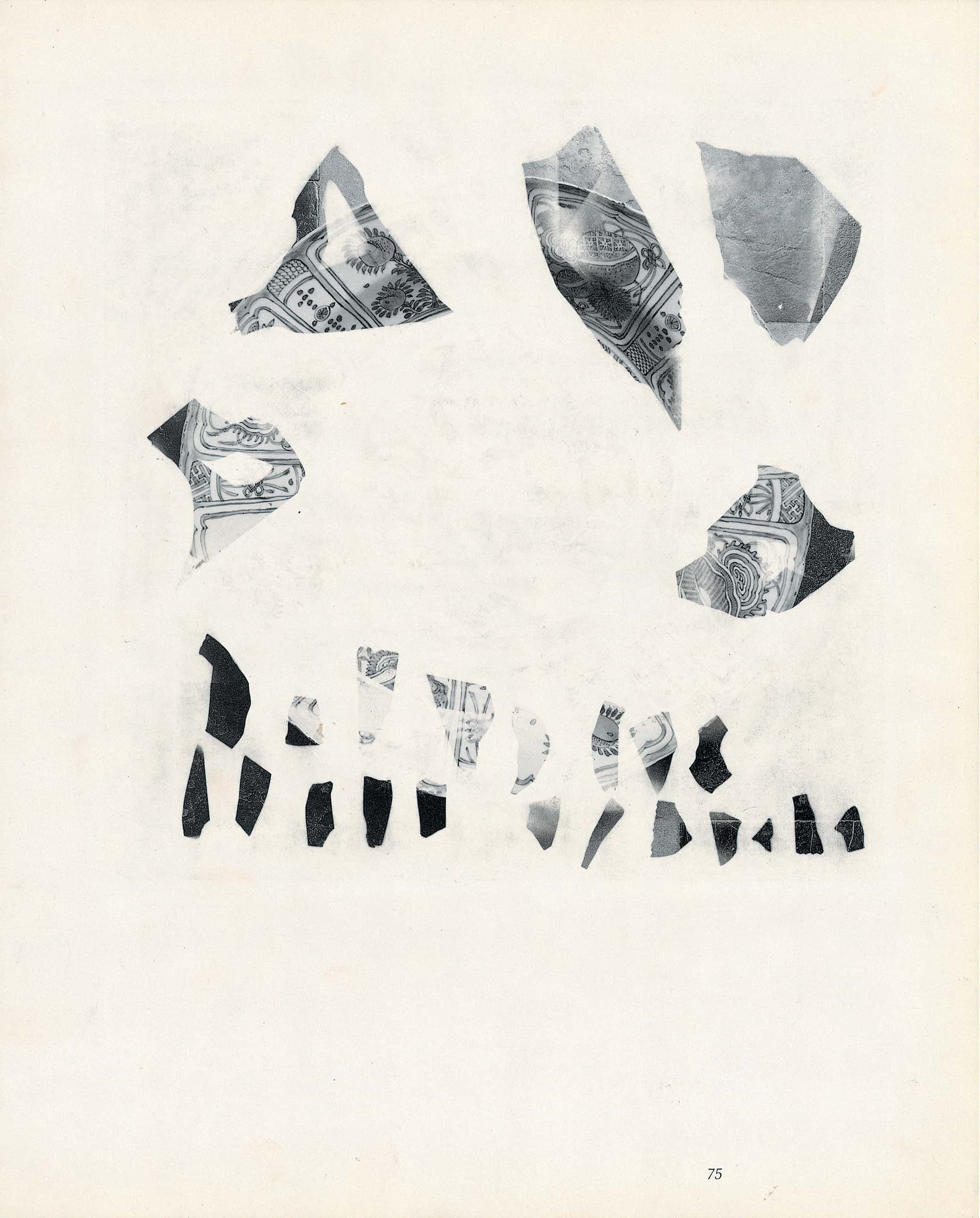

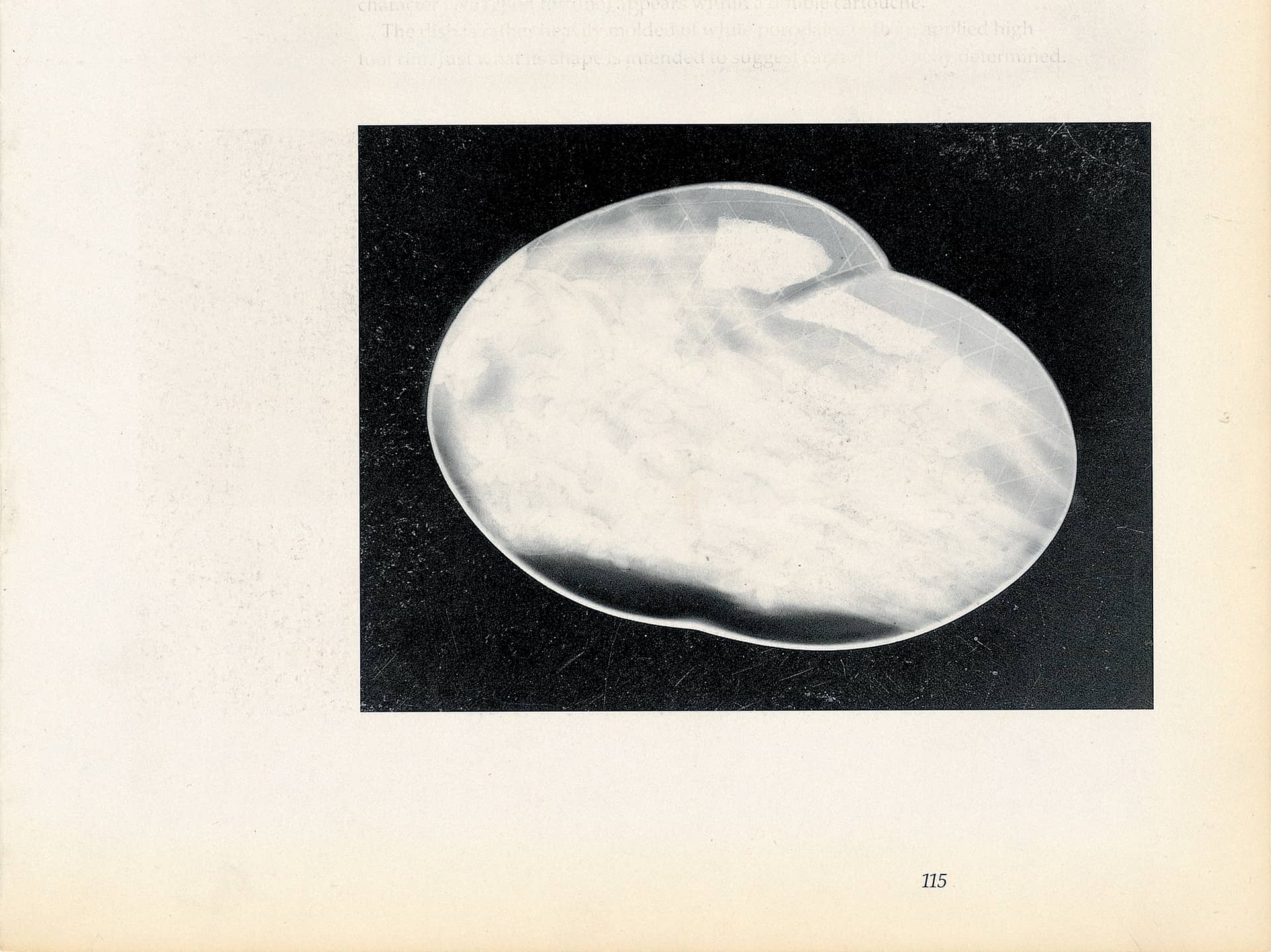

In her two-channel video projection The Place of the Fold, Benbenisty overlays images of the printing press with excerpts from Victor Guérin’s book Geographical, Historical, and Archaeological Description of Palestine (1868), which documents Arab villages in the area that have since disappeared. The second screen features a 3D printer, printing an object (Untitled) from white powder, superimposed with an image of Benbenisty’s hands printing a series of drawings (Land of Blue Oranges) on sheets of paper used to wrap Jaffa oranges, which she inherited from her grandmother—a citrus packer. In the drawings, the artist uses printing stamps made of orange peels covered in blue ink, juxtaposed with English translations of the names of disappeared Arab villages excerpted from Edward Henry Palmer’s The Survey of Western Palestine (1881).

The Fajja project evokes a printing machine that erases as it names. In each of these printing processes, Benbenisty revives places and symbols that have been overwritten through the years by layers upon layers of written text. The printed surface of a map or an orange wrapper reveals how historical projections, colonial manipulations, and orientalist imaginations imprint and modify territories, as typographical interventions produce new topographies.

Raphaël Sigal