Shahar Yahalom,

12:49

Ian: It seems like in the last few years your work has really gone back to the primal things that make us human, unmediated by technology.

Shahar: I think sculpture by definition is life; its the passion of human beings to create something with other beings in the world. The material is a being, and we can learn a lot about the world by studying materials, because that is what the world is made of.

Ian: It’s ironic that you mention life, when so much of your work – from the drawings, to the tombs, seem to vibrate with death.

Shahar: I think making art is very much about our fantasies, about everything that we don’t know or don’t see, or can’t reach, and death is the most dramatic fate that we will never reach. But I don’t even like to use the term death, I prefer the term ‘lifeless’. I’ve been a formal sculptor for almost twenty years. So every day I have this relationship with lifeless bodies, and I am committed to seeing the world from their point of view, from the point of view of the lifeless – which is there, it exists, it stands there just like me. It’s not that it doesn’t exist because of its lack of consciousness. It’s body is here just like my body is here. This thing was never alive; its exactly what I am going to be in few years…The lifeless and the living are constantly in flux, my fingernails are lifeless, for example. My body also has some lifeless parts in it. So this is not something that will happen at the end. No, it’s this lifeless thing that is always a part of us and everything around us.

Ian: I always want to understand with artists – where their preoccupations come from?

Shahar: I think my current obsession with lifeless objects comes mainly from just making sculpture and working with lifeless materials, but there is probably more to it because when I was 13, I was in love with Sepultura (a Brazilian heavy metal band from Belo Horizonte. So I must have some fascination with death, but I don’t know, it’s not the realistic death that we’re used to thinking about, it’s more of a fascination with the fantasy of things that are not alive, but still vibrate somehow. I mean, all this death metal culture is very much about the kingdom of of the dead, but it’s not about death in the realistic way we perceive it, it’s not about the way the living are mourning the dead, it’s about the way the dead are living, are alive in a way, you know, that’s what death metal is, it’s about music of death as if it were something which vibrates with emotion.

Ian: Tell me about the tombs.

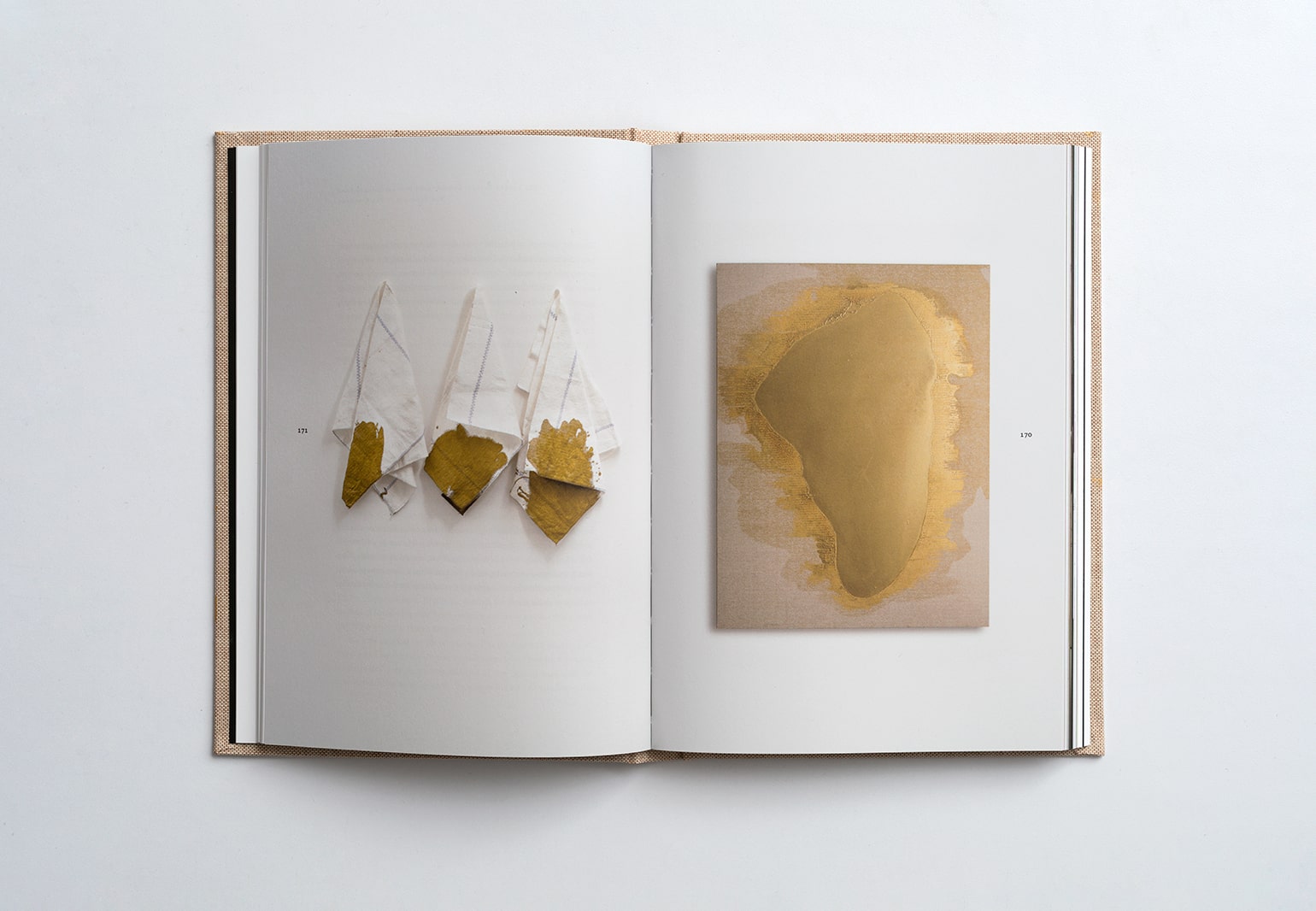

Shahar: The tombs are a series of plaster molds that were built on top of sculptures made by other artists. In these works there’s also some kind of struggle, but it’s a little different, it’s not between two images of mine struggling together, but somehow more of a struggle between me and my history or my spiritual fathers, like with Yechiel Shemi, for example, where I buried two of his sculptures. In other works, I bury the sculptures made by friends, and sometimes I even bury the people themselves. I choose sculptures that I find interesting and that I want to stare at for twenty-four, sometimes forty-eight and sometimes seventy-two hours – just stare at them and cover them with plaster until I have my sculpture made, but it’s very much a practice of studying someone else’s work, and then burying it and covering it, and to some extent, swallowing it into my knowledge – but on the other hand, I bury them, and I cover them, so you can only see the general principles of its form and shape.

Ian: Why the urge to bury? It immediately conjures thoughts about how we deal with the dead.

Shahar: Death is the only time we really take care of something that is lifeless. Cause usually we don’t really give a shit about anything that is lifeless. And then all of a sudden you take something completely lifeless and you take care of it, you wash it and you clean it, and you gently put it in the ground. And you actually think that this lifeless object still has a feeling. And I would say that’s something we can adopt into other lifeless things around us, you know, but it’s, it’s the caring that you see.

Ian: I was initially thinking about more morbid associations, but I see what you mean.

Shahar: It also depends what you mean by burying – this term can be thought of in many ways. For example, burying is also containing, and that’s also something that is very much rooted in everyday life and mainly in our very primal stage of life, which is being buried in our mother’s belly. These terms are not terms of determination, but of actual, ongoing living processes, just like ‘death’ and ‘lifeless’, they’re kind of the same, but we think about them very differently because the chair is lifeless, but the chair will never be dead because it was never alive. Take for instance this piece – there’s a sculpture of a woman and a child that I have to protect when I create the mold, and the way to protect them is to cover them with plastic. You think it’s choked because you look at it from your breathing perspective. But a lifeless object doesn’t need to breathe. It needs to be contained.

Ian: It’s funny, when I first met you in your studio, I was initially struck by the darkness to the work, its rawness, the black and white markings, almost a gothic feeling, so it’s funny that we find ourselves speaking of death, but in a different context then I expected. But I was noticed the primacy of the work, lots of images of women holding children, holding birds, void of modern objects or artefacts. It feels timeless – other than the cigarettes.

Shahar: Before the 20th century there was no sculpture of still objects. You wouldn’t do it. There was no point sculpting a helmet. The helmet itself was a sculpture – that’s why you wouldn’t sculpt it, because the helmet was a sculpture made by a certain artist. And then in the 20th century, we don’t have artists making helmets anymore because we have machines making helmets. I don’t make sculptures of still objects ’cause I think all objects – even functional ones – should be counted as ‘sculpture’ – should be related to a subject, someone who wants this object to exist on a personal level. Something that was made specifically to be what it is, with care, as opposed to generic processes of mass fabrication.

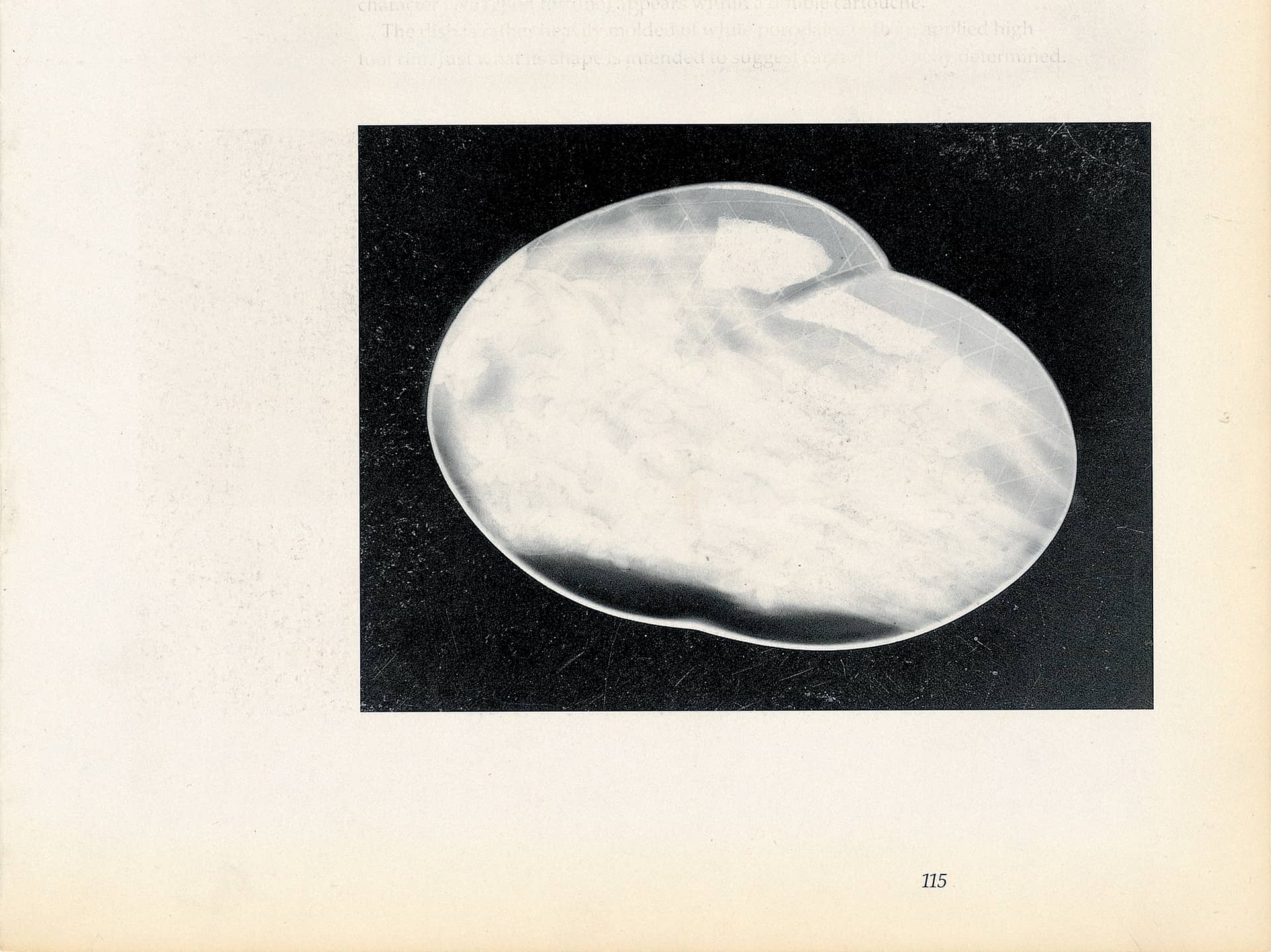

Ian: The glass heads is another significant body of work that you have just exhibited at your exhibit at Bat Yam Museum of Art. I am curious to hear about how this body of work developed.

Shahar: I want to refer to a drawing from the book – this for example is an etching of a drawing I did of a head sculpture of a head sculpture I got from my sister – she did it when she was fourteen – and I saw this head sculpture and it blew my mind. I was after my first degree in art, making big installations – and I realized that these large-scale installations were no longer serving me, and I moved to more hard-core sculpture I would say. The glass heads started about three and a half years ago – they are sculptures blown into hot plaster molds, a practice which was used a little differently in ancient Rome – I made the adjustment to up-to-date materials like the plaster, which gives you a new quality because you can heat it up, unlike like the molds used in ancient times. When you heat up the plaster, the glass can really be blown to the ground zero of the mold, and then you can get all the details, imprints of fingerprints and any tiny trace that was made on the first model, is replicated in reverse in the mold, and then transformed into glass.

Ian: It looks like there are always multiple figures, as if the head were turned into some sort of embryonic sac.

Shahar: The main principle of this body of work is that each head has to contain at least two figures and this principle turns it from, let’s say a figurative work of a sculpture of a head – into kind of surrealist sculpture or a rebecause when one head contains two figures that kind of struggle on the volume of the head, so it becomes about relationship. I would say that struggle is the main idea of these sculptures – how two figures can share one space. On a very practical level – if one figure needs to have a big nose, the other one has to give up the ear, because you have to share the space somehow. So you have to share the organs also in a way.

Ian: I am curious about this pre-occupation with sharing space. Has this always been a pre-occupation of yours?

Shahar: I grew up on a kibbutz. I was raised in a ‘children’s house’ from the age of two months until I was grown enough to have my own space. Sharing space is a part of what I have always been practicing. It’s not something that I think about often in relation to my work, but I’m sure it’s there. It’s in my DNA.

Ian: It sounds like this was really hard phenomenon – of removing kids from their parents.

Shahar: In retrospect [because I don’t know what I felt back then – I only know what I remember today], it was mainly an experience of tons of freedom, which is a good experience for me.

Ian: When you talk about being a sculptor, isn’t the consideration of space always a primary concern? You once mentioned that even your drawings were also a method for exploring sculptural principle. What does it mean to be a sculptor – in terms of the relation between the physical and the psychic.

Shahar: One shapes his practice through the years in relation to his personality, and needs, and things that you don’t know ahead, you discover them as you go along. Through these years of practicing art, I realize that the physical work is something I need to do. Therefore sculpture is my mediumthe world, which doesn’t need sculpture. In fact, it doesn’t even know what to do with it.

Ian: You mean in the sense that our increasingly digital world is doing away with matter?

Shahar: In the past decades there has been a movement towards maximum software, minimum hardware – that’s the direction of, of the world, it has to do with our economy, and sculpture is exactly the other way around. It’s the most, de-coded knowledge. It’s exactly what is there. The technology is minimized – in hardcore sculpture, I would say. In a way it’s going back.

Ian: You mean in the sense that our increasingly digital world is doing away with matter? Is your position anti-modern, anti-technology?

Shahar: I wouldn’t say my position is anti-anything, and definitely not anti-modern, because I wouldn’t go back, I wouldn’t miss anything. And every change that is happening is good, because things need to move, but I think for me, in terms of my own subjectivities – genetics, education and experiences, I felt a need to focus on the more primal aspects of what makes us human, and this led me to adopt practices of the ancient Romans, and put these works under contemporary eyes.

On Installation

Shahar: I think in the past, or in the first 10 years of my artistic practice, there was no separation between the art making and the exhibition making. And that’s something that is. A byproduct of the installation age, which I’m a, like a pure product of, I was educated by artists who believed in or thought installation: The 20th century is about installation, it’s about the contemporary, about the space, the here and the now; and that’s the meaning of installation, and that’s how I was thinking about my sculptures back then.

I think in a way we were taught, at least in the philosophy of culture, or the philosophy of art, to trust ourselves; so the self is the point of reference. I think the installation phase has a lot to do with modernity’s conception of the self, and of the self as the only destination of itself. The here and now is the only thing that the self can perceive. So the here and now is the only reference for art in general, I would say for the 20th century. And I think the idea of separating my art from the ideas of installation and bringing them back to more primal ideas that has to do somewhat with my ‘self’, but has to do a lot also with considering all that lies beyond consciousness. I think I’m trying to give faith back to the things that are outside of myself.

Ian: It’s probably also a happier way to live. It very much reminds of me of Eckart Tolle’s The Power of Now – where he argues that happiness and peace come from connecting to the things that are beyond our mind, and that the overstimulation of our ego’s has resulted in the rise of collective anxieties.

Shahar: But at some point I came to a dead end. I realized that I have to make a separation, the work of making art, the daily practice, and the premeditated nature of creating an installation are two different things. Completely separate. And I have to keep them separated, even though the world wants me to turn them into one all the time. When I separated the art from the exhibition, I started making art for endless times and spaces, so that it can roll, and it dictates a certain character for the sculpture. For example, it cannot be too heavy because you cannot move it from place to place. If it’s too heavy and it cannot be too big because then you have to have a public organization to contain it. But if it’s small enough, even one person can contain it, by living with it.

Allowing the work of art to keep rolling in the world through times and spaces is an idea that completely contradicts installation. And it’s a practice that tries to think eternity, almost a word that you shouldn’t say in relation to art. So it’s a completely different set of values that doesn’t think about the now and here and contemporary, what will be tomorrow, and how to be ahead of time – No, it’s a practice that tries to think what happened before, long, long before I was born, maybe when the first human just arrived and what were his expectations from art and sculpture.

Ian: I find it really interesting because I think alot of us have similar impulses – in light of the digital revolution we are living through.

Shahar: I don’t like to talk too much about philosophy – as I am not a philosopher – I want to talk about glass!!! Art is made by humans for humans, but it exists in a sphere that contains many other beings, which it has to involve in order to exist. And there’s something about contemporary thinking which gets rid of everything that is not the self, and it’s way of perceiving itself. And I think there’s something about looking out and realizing that the world is containing more than consciousness. I mean, I can go back to the Descartes. I am not because I think, I am because my body’s here, Descartes got rid of everything, of all the bodies, and then he got to the conclusion that the only thing he can trust is oneself. So I am here, but all the rest is not here. And I’m saying, no, I’m here. Even if I stop thinking, I’ll still be here. I’m here because my body is here, this sculpture is also here, and the fact that I think, is another aspect of me being, but it’s not the main issue of my existence, and sculpture is not about being able to think, it’s about being able to touch, and to exist on the most physical level.

Ian: Are there times in your personal life when you’re not making art because you just like being a person in the world?

Shahar: The understanding that the work of art needs to be separate from the exhibition and the public sphere and the political has to do with the fact that I realized that it has to be connected to my personal everyday life. And so if you ask me what I do, other than making art, I have a hard time answering because my studio is inside my house, where my son plays with my sculptures, he would drive his little cars on them. And these gestures of his are part of my art. I mean, it’s ideas that he brings. (Pointing to a piece) He sat on this sculpture for a year. I mean, this sculpture was done two and a half years ago. It was in our living room and my son was doing tons of stuff with it. He broke it. I fixed it. So art is completely within my personal life, within my home space.

And in that sense, the space of my art is not the public sphere. It’s not the museum, it’s the living room of one human being. And in that sense, it doesn’t matter if it’s me or a friend of mine or anyone who’s taking the responsibility of caring for this lifeless object.

Ian: What do you say to people will look at your work and see something very dark, very grotesque.

Shahar: I’m trying to make beautiful things. They seem to end up very black and grotesque, and I’m trying to be honest about my experience in my heart, and I’m trying to find beauty, but beauty often is discovered in the most dark and grotesque places.

Ian: I am curious about the decisions made as regards the book – in reference to this idea creating works that can roll through spaces and times.

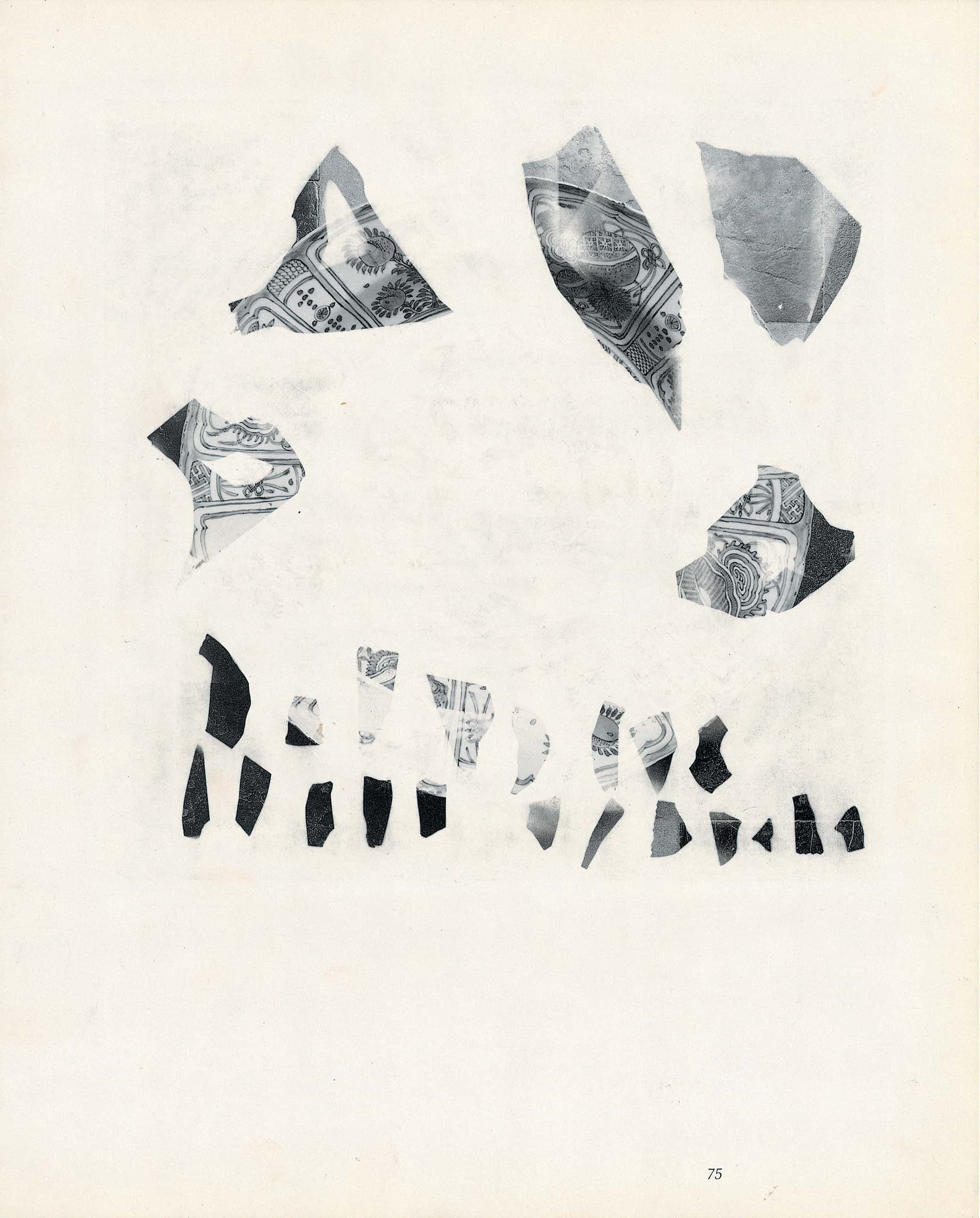

Shahar: The way I chose to compose the book is really to emphasize this idea that the work of art is independent from the space of viewing art. None of the sculptures are photographed inside an art space, or in a studio. All the works are shot somewhere in the world during their lifeless life of rolling from one place to another, The chapter of the tombs actually shows how these molds are made, so you can see also the sculptures that are buried inside.

The second book, Blind Arch is a collection of carbon paper drawings made by scratching images onto folded pages, so that they can fit into my pocket. The drawings duplicate through the carbon, creating these motifs that pop into my head, and during these two years of COVID, while I spent most of the time with my young son, every time I had a minute, I would take the folded paper and scratch a little drawing with a stick or a head pin. It’s like a visual journal, but since I don’t write, I work with imagery.

Ian: Where does the title Blunt Liver come from?

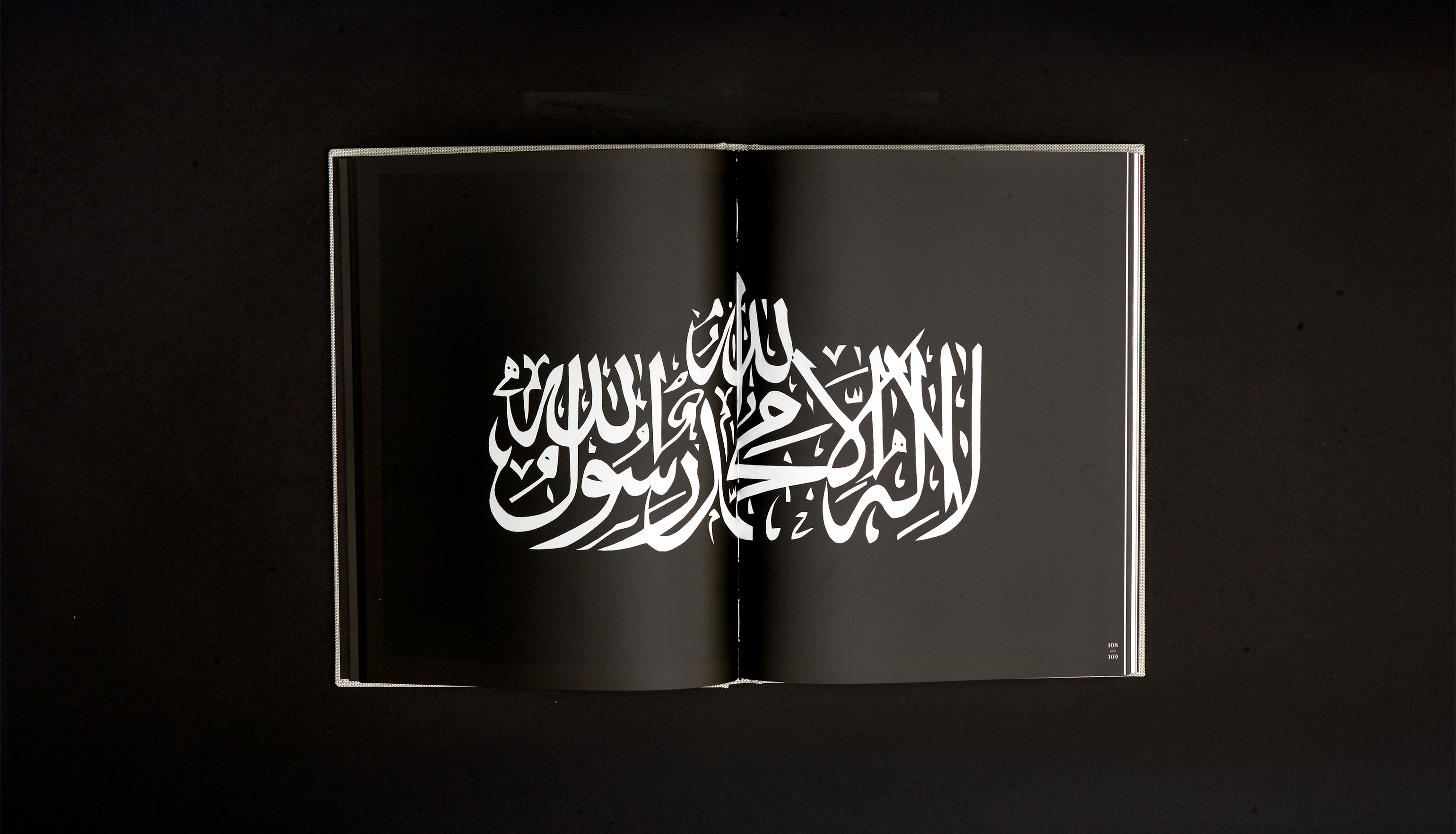

Shahar: Blunt refers to something which isn’t sharp – neither as shape or even as a thought. I like to think about this word in relation to my work – because both a tomb, or even a container are rarely sharp – they constitute an exterior surface for protection. And glass is only sharp when it breaks, when it’s whole its surface is blunt. Also, think about how materials are made ‘blunt’ – exposure to water and air erodes and smooths surfaces – kind of like how life makes us blunt as we age.

Shahar: I like how the word liver also contains the word life, which touches on a central question in my work, what does it mean to be alive? The liver is an organ that is very bloody, very sensual and gory, very much rooted in corporeal feelings within the body which don’t have to do with our mind.

Ian: Let’s talk a bit about the book. Tell me why you think the book is such an appropriate form for the work.

Shahar: It’s hard to compare the book to the exhibition because both of them create a certain perspective for the works. If the exhibition crucifies the works in time and space, the book crucifies them in a flat image, but allows them to keep rolling in time and space. So I think the different forms complement one another.

___

Shahar Yahalom (b.1980, Israel) received a BFA from Ha’midrasha School of Art, Israel (2006). Graduated MFA at Colombia University, New York (2014).

Yahalom’s works portray intricate scenes that often perceived as amorphous occurrences but a closer look reveals that each sculpture contains multiple bodies stuck to one another. The sculpture fuses the figures together and randomly suspend them in time. The result is a structure that undermines the inherent hierarchy of the moment that it represents, an existence that is static, frozen, and indifferent, an immortal artistic object that does not change. These properties do not stem solely from the immortality of the object, but also from the fact that it was never alive. The appearance of the sculpture as a still object that represents a living body establishes an equation where the very dimension of life is the unknown variable.

Yahalom is a recipient of The Bronner Residency, Goethe Institut and Kunststiftung NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany (2019), Encouragement of creativity prize, ministry of culture, Israel (2017), Sharpe – Walentas studio program NY (2014) and the Young Artist Prize Israeli Ministry of Culture (2011). Exhibitions include: Odile Ouizeman Gallery, Paris (2019), “Nut case” Noga Gallery Tel Aviv (2018), NBL Project, Void Gallery, Derry, Northern Ireland (2017), “Walter Benjamin, Archive/Exile”, Tel Aviv Museum (2016), Zabladowicz Collection, London (2015), The Armory Show NY (2015), Inside-out Museum, Beijing (2014) Aran Cravey gallery LA (2014), Macro Museum, Rome (2013); Noga Gallery, Tel Aviv (2012) “Culturescapes” Basel (2011); Tel Aviv Museum (2011); The Armory Show, New York (2010);Herzlyia Biennale (2009); Herzlyia Museum (2008).