6:47 min

This film was shot over several years ago at Odili’s studio in Philadelpia, and was edited on the occasion of the publication of Odili Donald Odita, it synthesizes footage of him at work, with a video documentation of the edition. Edited and directed by Ian Sternthal.

Ian: How did your family ended up in the States?

Odili: I was born in Nigeria in 1966, right before the start of the Biafran War, a civil war precipitated by the Igbo’s desire to separate from Nigeria. While it was publicized to the world as a religious war, essentially it was a war of ideology and belief. I’m Igbo, and my family left Nigeria for the United States due to the war, which the Igbo lost. Millions were killed in the process. Had we won, my people would have been called the Biafran nation. Nigeria quickly developed from the 1970’s onward; there was an optimism that emerged and continued through the 1980’s. Simultaneously corruption was building, and eventually took hold of the country, Nigeria remains a rich country, but there’s a lot of inequity and a lot of mismanagement.

Ian: Did your parents have a hard time adjusting to life in the U.S?

Odili: Before I was born my father had gone to Indiana University on an academic scholarship to study art, so he was already somewhat established in the U.S. We initially moved to Indiana and then to Iowa, where my Mother got her degree, and then to Columbus, Ohio where I grew up from the age of four. My father, who was one of the Zaria rebels, started the history of African art program at Ohio State university in the 1970’s.

Ian: Who were the Zaria rebels?

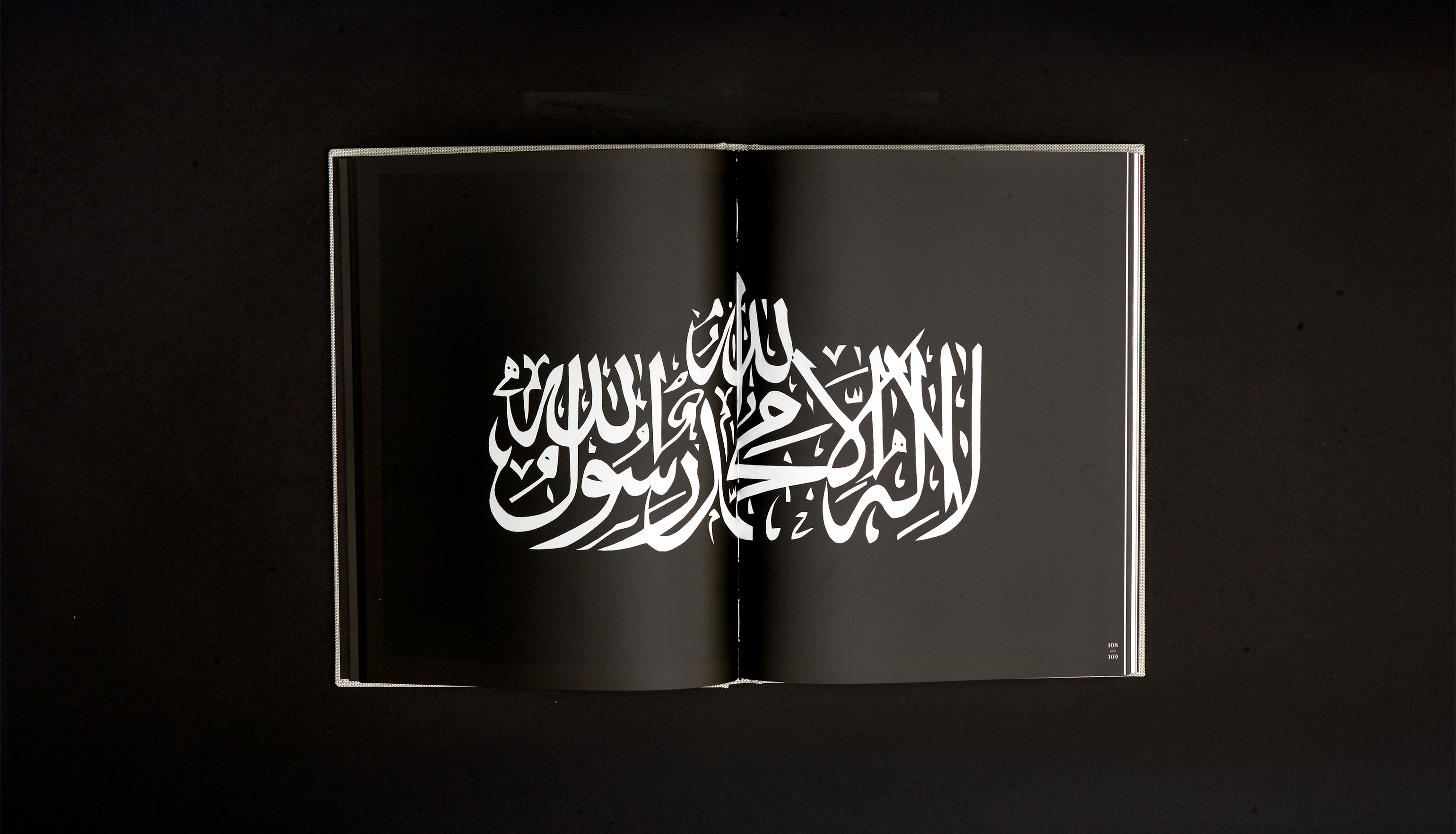

Odili: The rebels were a group of academics who wanted to synthesize African and Eurocentric perspectives into their practice as artists. They were intent on incorporating traditional indigenous African concerns into the academic curriculum. They’re still known today for their contributions to modern art in Nigeria. There were 8 of them, including Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Sam Grillo, and of course my father, Emanuel Odita, amongst others. They were professors at the Nigerian College of Art, Science, and Technology – known today as Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria. My father continued promoting and sharing Nigerian art with the world when he came to the United States.

Ian: Your work expresses a lot of dualities – what was it like growing up in the United States in a Nigerian household?

Odili: My ‘American experience’ was confusing in the sense that my household was very Nigerian, both in the way that we ate food and interacted with each other. The only thing lacking was the language, and our physical displacement. When I was in first or second grade, my teachers wanted to hold me back because they said I wasn’t making any sense in school. My father worried that I might be mixing English with Igbo, so they decided to stop speaking Igbo to us. Today we know that you can speak multiple languages with children, and though they may take longer to speak, when they do, they can compartmentalize various languages. I grew up in a household where the concerns were more international, as opposed to school – where everything was very local – to do with American politics, Football, and news. I felt like I was always living between two worlds which rarely intersected. If I brought up Nigerian issues in school – they wouldn’t know what I was talking about. And when I brought those concerns that I got in school back home, my parents really didn’t care. Growing up in a space of simultaneously diverging realities forced me to contend with both, and my process in work as in life has been to try and unify disparate realities.

FLAT COLOR

Ian: You famously said that “Color in itself has the possibility of mirroring the complexity of the world as much as it has the potential for being distinct.” Tell me about how you started painting.

Odili: My first experience in a painting studio was with my father. I remember being as little as seven or eight years old, helping him stretch his canvases, applying the rabbit skin glue, cooking it, and gesso-ing his canvases. He taught me, and I would watch him draw and paint. His work influenced me in the sense that it I looked at it all the time – his paintings were all over our house. I studied the way that the colors were applied and placed on the canvas. Though the work was figurative, the way he structured color on the canvases largely influenced the way that I see color in space.

Ian: Is your own use of flat color derived from this tradition?

My father’s color was flat, although he modulated the way that the color existed within the spaces and shapes he created. As within cubism, or Picasso’s figurative works, his colors were laid down as shape, which came together to make figurative forms. When I look at the treatment of space in my canvases, I understand that although some of the fragmentation within my own work is related to his, my work has a more conceptual, almost physiological relationship to color. His color was used as pattern; as within textiles, his palette has more of a descriptive quality. I use color to create spaces which engage the viewer’s body, works that depend on a symbiosis with the viewer’s perspective, in the construction of a virtual space.

Ian: Is there something African about the idea of flat color or clearly defined spaces of color? How does this connect to the history of African art or African textiles?

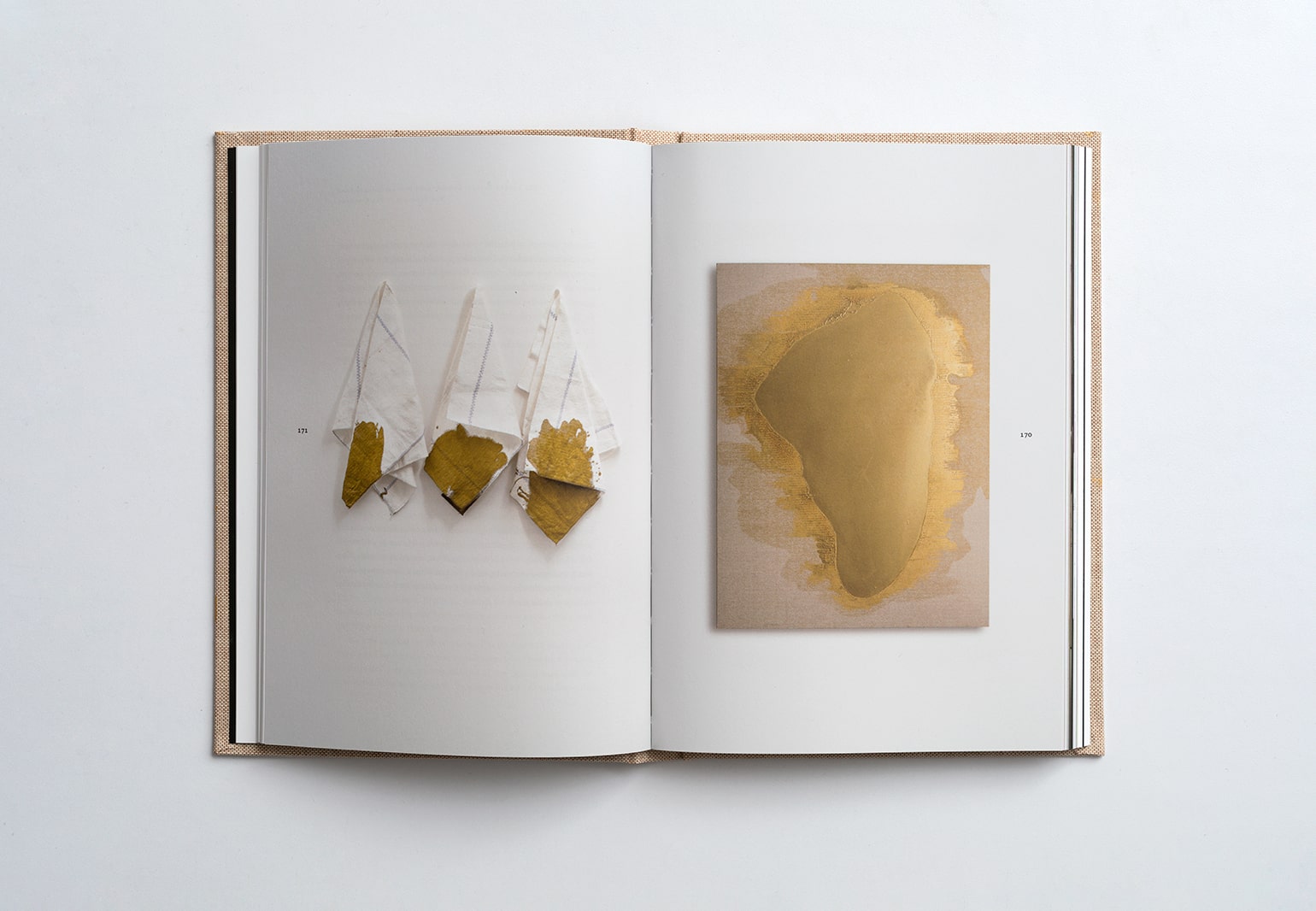

Odili: There are two types of African textiles; those which were indigenously produced, and those manufactured in Europe and distributed throughout Africa. It’s an interesting phenomenon which was dissected in the work of the Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, who creates large installations with African ‘batik’ or textiles, in order to ask a question I frequently think about – what is Africa? What is African? My paintings allude to African forms found within these textiles, but they are not representations of these textiles. I am using these ‘tropes’ as a reference to create a new space – conceived either virtually, actually, philosophically, emotionally, or politically. Playing with these tropes is but a point of departure, from which I go on to fragment and unify space through colors. Juxtaposing colors, placed against another colors, proposes a notion of togetherness and non-togetherness, a simultaneous movement both towards and against, derived from within the paintings aesthetic dimensions.

Ian: Would you say that your palette has brightened over the years ?

Odili: My color has gotten more intense over the years. Formally speaking, I have gotten better at creating color combinations, but in a conceptual sense , I feel my palette has gotten closer to African colors. Earlier on in my project I was thinking of African color in the sense of how I saw it through memory, dusty, the earth mixing with color, eliciting a chromatic power for the sake of getting this naturalness with the Earth. With this idea, in this sense, it’s this romantic idea of Africa. Early on in my practice, I was thinking of how to define ‘African color.’ I would look at textiles, and cloth patterns, and I realized that there’s no end to category, that to be ‘Africa’, it didn’t have to be bound to my early romantic conception of ‘African color.’ This realization enabled me to open up my relationship to color, formally and conceptually. The wall work helped me be open to how I see and compose color; which in turn influenced my canvas painting. In essence, the canvas paintings helped me to formulate the drawing in my wall painting and then the color in my wall painting helped to advance and complicate the color in my canvas painting.

NEW YORK CITY

Ian: How are these concerns made manifest in the work? When did you move to New York? How did being in New York change your artistic process?

Odili: I went to New York when I was 24, right after finishing graduate school at Bennington College in Vermont. New York was a place that I had wanted to go to ever since I was a kid. Growing up I collected comic books, listened to a lot of music, and watched a lot of T.V. –media spaces where New York City was heavily represented. It was a place where I longed to be, where I felt I would be free to experience and express myself. In the beginning it was hard to adjust, I had to learn to live there. New York is a microcosm for the world, and I was able to assume and accept the ‘difference’ that I struggled with growing up in a suburban, homogeneous space like Columbus, Ohio. When I was in New York I gathered a lot of different energies, I worked with different kinds of artists, and it gave me the confidence to grow as an artist.

Ian: At your first solo show in New York, ‘Color Theory’ at The Florence Lynch Gallery in 1999, you showed a series of geometric paintings which seem to fuse the flat color of the African tradition with these vanishing points and infinite geometries. I’m curious as to the origins of these works.

Odili: When I first moved to New York I got a job working for a company called Stitch King, which made computer-embroidered logos on polo shirts. We worked with Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator 1.01. These programs presented images in a virtual, endless, and deep space. These ideas expanded the way that I was thinking about painting. Digital technology made me question notions of beginning and end, and think beyond the frame, to imagine what lies outside of the ‘boundaries.’ The paintings I started making at the time grew out of these questions. I was starting to think about painting as way of depicting virtual space, unconfined by the material constraints of the two dimensional world.

The paintings you referred to do indeed incorporate a triangular geometric formation that is African in origin and conceptual in intention. A triangular block of color starts from one point, incrementally expanding as it reaches the other end of the canvas. The motif expresses the mathematics of infinity – two lines that never really touch, expanding towards infinity and beyond. This structure begs the question of what happens when the line reaches the edge. Does this space continue beyond the canvas, or does it just cease to exist? The triangular shapes stacked above and below move in opposite directions, constantly repeating. This idea came to me from staring at the computer screen, as well as the cinematic screen. When I would see the credits at the end of a film roll off the screen, I wondered whether these texts continued to scroll upwards even though we don’t see them anymore, or do they cease to exist? This idea of the edge and beyond – the edge and within – was something that I began applying towards my understanding of the Western World’s boundaries, in relation to the surrounding ‘peripheral’ areas.

Ian: This questioning of hierarchy and ‘decentralization’ links up with contemporary philosophy’s larger project of deconstruction – to do away with Western philosophy’s metaphysical pre-occupations.

Odili: Traditionally, Western painting has been concerned with the space that lies within the four edges of the canvas. Everything within the canvas is ‘real’, and everything outside of those four edges is peripheral to reality. I started to equate this bias to my experience in the West. The canvas’ center is analagous to the euro-centrism of Western consciousness, with everything outside reduced to the ‘space of the other’, the third world. It was interesting for me to use basic shapes to address broader philosophical and political issues.

ABSTRACTION AND POLITICS

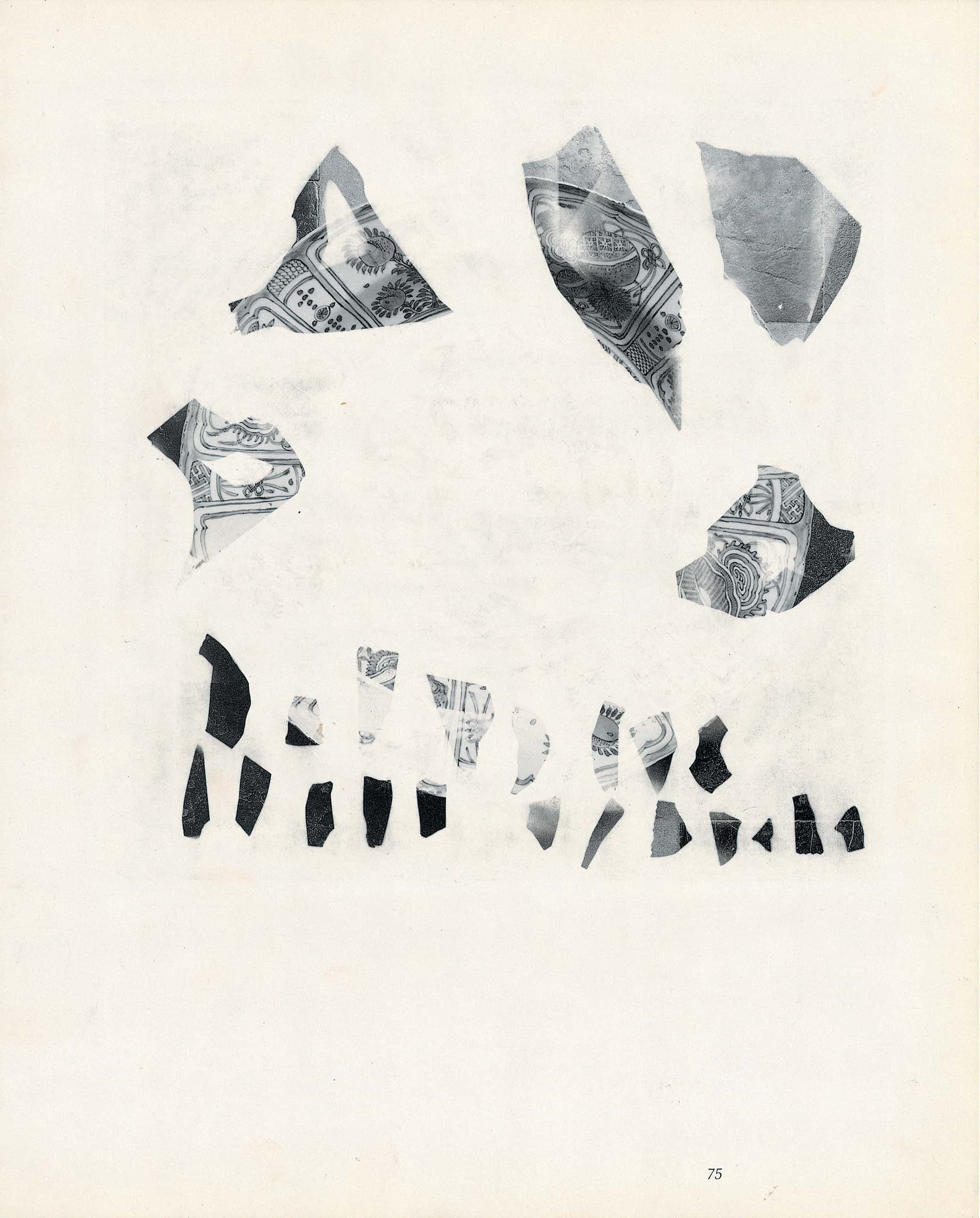

Ian: I noticed in your first solo shows you were showing abstract work alongside multimedia collages made with found images related to race, which seemed heavily involved in an investigation of your own identity. Was this a result of the influence that new media was beginning to bear upon your painting?

Odili: The reason for incorporating the photography with the paintings was to situate the paintings within a certain context. I knew early on that if I showed the paintings by themselves they would immediately be considered within the tradition of Western abstraction. I didn’t want my works to be considered only within relation to artists like Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland or Peter Halley. I wanted to be able to have this dialogue go beyond the West and into the space of Africa, the space of the other. So, I felt I had to use those photo-based works for contextual reasons. In essence, I was bringing my curatorial practice into the realm of my artistic practice.

People question how effectively abstract work can function politically, inferring that the lack of ‘recognizability’ within abstraction somehow hinders the political potential of the work. I think that the political significance of abstract work has to consider the process itself, of how and why the paintings are made. This, coupled with the way they are read, is part of their broader social context.

Ian: It seems to me that your use of abstraction echoses ‘the essence’ of the multimedia collages you were also making at the time, through the disorientation and confusion of hierarchy achieved through your placement of flat color.

Odili: The flatness of the colors in my work creates a tension which emerges within the canvas; Colors are laid down to create forms which dissect the canvas into various color segments, which through their pairing – beside, under, and over one another – become simultaneously dominant and subordinate, blurring the lines that traditionally divide foreground from background. The technique does away with hierarchy. The push and pull of the colors transform the ‘forms’ into a ‘space’ which merges illusion with reality, fact with fiction, inauthenticity with authenticity, without privilege. This concept connects to those preliminary questions I grappled with during my initial experiences with Photoshop: What is there, what is not, what is beyond. I hope each viewer who contemplates the work connects to these thoughts of ‘here’ and ‘there’, which emerged in response to my relationship with Nigeria, and my experience in America. Is my American life the real one or my African roots? Am I creating spaces that filled with my experience, or are they portals for others to fill with their own experience? The work constitutes what I consider to be another kind of knowledge, one that transcends existing realities.

Ian: Your early work is more literally connected to identity politics – whether it be through the integration of pop culture imagery into mixed media works, or the curatorial decision to show abstract paintings next to media that informs and contextualizes the work, whereas your more recent works and your later work becomes more abstract. Are the political issues related to race and geography still present within the abstract?

Odili: Identity politics are as prevalent in my abstract work as in the more literal pieces I made earlier on in my career. In my earlier work, the political messages were more didactic, communicated through direct imagery, and photographs from pop culture. With the paintings I address political notions through concept, process and action. On one hand, the paintings are very real they’re color on canvas. I don’t distinguish between abstraction and figuration. On the one hand I see my work as existing partly within the tradition that’s called abstraction, but ultimately I have a problem with the concept of abstraction because everything in the world is real to me. A straight line across a canvas space is representative of a horizon line, or even just of a line. A line is as real as the difference between sea and sky, or between land and sky.

I’m interested in speaking to the world through color, line, and form about my experiences. The duality of my life – of being African and America; this sense of one the one hand always being in flight, uncomfortable, in this place of homelessness and dislocation, and on the other of searching for unity. My conception of home is rooted in desire more then memory. It is something that I search for through painting, and often find within the colors as they’re brought together in the canvases. The colored mosaics I make represent a self made of fragments, which together construct a whole. In that sense I relate it to the African experience in the world, the African diaspora, which has had to make its home in the entirety of the world. I feel very lucky to be able to have this practice that I have now where I am able to communicate in ways that go across national boundaries.

ON COLOR

Ian: Do you feel that your work is about kind of healing of public spaces with these vibrant colors? You made a recent installation at the New York Presbyterian Hospital?

Odili: To a certain extent I think that that’s very true. I think that an artists work is always somehow an attempt at communicating individual concerns and interests in the world. I don’t know how effective art is in actually make effecting change, lets say in a political sense, but we can be influential as artists. We can make suggestions. We can comment on the world that we live in. I think that is the strength of the artist, to be agents of change in the sense that they communicate their wishes and desires to people. This is what I try to do in my work. I try to think about the spaces that I use my painting to speak in and about. The colors are often an attempt at healing.

Ian: Can you speak about the musicality of your work? And does music influence?

Odili: Music and musicality are very essential to my work, compositionally through the drawing, and emotionally through the color relationships woven into the works. There’s a rhythmic pattern to the shapes and the colors applied, which together create something bigger than any one element. This musicality is also experienced by those who absorb the work through their eyes and bodies.

ON IDENTITY AND AUTHENTICITY

Ian: This question of authenticity appears repeatedly in your works. Tell me about ‘The Authentic African’ piece, and how it was received, both in Africa, and in the United States.

Odili: The Authentic African’ emerged as question and a response to what I thought was a uniquely American question: Are you authentic? Are you an African? When I was in grade school I remember being asked what it was like to live in Africa. Would I have had to dodge snakes and lions to get to school? I placed each image above two checkboxes with the words ‘yes’ and ‘ no’ written, reminiscent of multiple choice questions in educational testing. The viewer is conceptually asked to ponder which is the authentic African. I had four African types in that series: The soldier, the businessman, the traditionalist, and the poor boy – I called him the poor shell boy in that series. The ‘Authentic African’ refers to this question of identity, posed from an American gaze looking at my ‘African body.’

Ian: Does this question of authenticity emerge solely from an American perspective?

Odili: I was invited to exhibit in South Africa during the second Johannesburg Biennale curated by Okwui Enwezor in 1997, and I went back again in 2006 to have a group show, and later on for my first solo show. The question of authenticity was posed to me from the South Africans. I was asked how I could still speak of Africa not living in the continent, not rooted within the soil? Could I understand the context of Africa from abroad? I was offended and surprised that an African would challenge the legitimacy of my voice. I believe that I am an agent of Africa. I carry it in my heart and my mind even if I am not physically present, like a satellite. In many ways my circumstances are the result of a massive brain drain; political and economic situations forced us to relocate elsewhere in order to survive. Having been born there, and raised with an African mentality, I am connected to the continent no matter where I am living.

Ian: Tell me about the pieces you created for the Biennale.

Odili: I created a series of billboards and bus shelter posters for the Johannesburg Biennale. The bus shelter posters showed a piece called ‘Endorfin’ sonically connected to endorphin, referring to an energy rush, but alphabetically spelling end or fin (which means end in French). The image was of the dancer Bill T. Jones. His body was split in half horizontally by a target. In that specific image, I was identifying the black male body as a living target. This work was made within the context of South Africa’s reconciliation trials, where the past atrocities of apartheid were examined in court. This piece was very timely, and it affected many people in the community, to the point where many people stole the signs and posters from different locations around the city. Unfortunately, I never got to see the work because of the situation in South Africa. The show signified an important first step in the growing globalization of the art world.

Ian: You also exhibited ‘Off Center’ there. Tell me about the work.

Odili: Off Center symbolizes the condition of the African in the diaspora. We have no center, in the sense that we didn’t have a place we can return to with a safe feeling of home. In the world we’re never really safe, we’re always foreigners or foreigners in a strange land. Having to find ourselves, and our center, without the material components.

Ian: At a certain point your paintings literally exploded off of the canvas, and onto walls, floors, ceilings, literally enveloping the body in a way you were previously only alluding to. How did this come about?

Odili: In September of 2003 ‘A Fiction of Authenticity’ opened at the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis. The curator hung three large paintings very close to each other, it was the first time that I saw the paintings working together, existing as a wall. I had made a painting on the wall for the first time in 1999, but that work didn’t approach the wall as an immersive experience with multiple vantage points. When I saw the three paintings together, I understand the potential of the wall, where one could experience the work through walking, as something I could work with and push further.

FROM THE CANVAS TO THE WALL

Ian: How did you push this further?

Odili: I had the opportunity to make a wall work in 2007 at the 52nd Venice Biennale for Art. Rob Storr, the curator, invited me to create a work in the central entry part of the Italian Pavilion in the Giardini. The wall that I made in Venice was entirely encompassing in two directions, covering two intersecting hallways. The work was partially a reaction to the canals that divide Venice. The walls were horizontally divided in two – with a row of lights in the center. I covered the space above the lights with colored arches, representative of the architectural richness of Venice, but also as an elusion to the heavens, or to ancestry. It was a celestial space, coning and sheltering the color-space beneath. The piece was called ‘Give me Shelter’, a large experiential painting that created both a transitory and a sheltering experience for the viewers. I wanted the painting to act as a shelter for those who passed through, where they could feel safe, at home, and blanketed by the colors. It worked on so many different levels, and with this work many people began to grasp the possibilities. Painting originated on the wall, but beyond that, the installation showed how painting could speak about trans-cultural experience through the use of a space as a canvas – incorporating the viewer within the space, rather then having them merely look from the outside.

Ian: After Venice, it seems like the geometric patterns begin to complicate. Can you speak a bit about that?

Odili: ‘Give Me Shelter’ opened a lot of doors for me. After Venice I started travelling more to create site specific works that transcended the canvas, and for each project I drew inspiration from the new contexts I was making the work in. I usually start by researching the building, or the geographical region where the piece will live, drawing information from these environments in order to inform the design – in terms of the colors and the formal shapes

Ian: Can you walk us through the process of how these works are made? Do you start it with drawings on paper? Is it a mathematical diagram…?

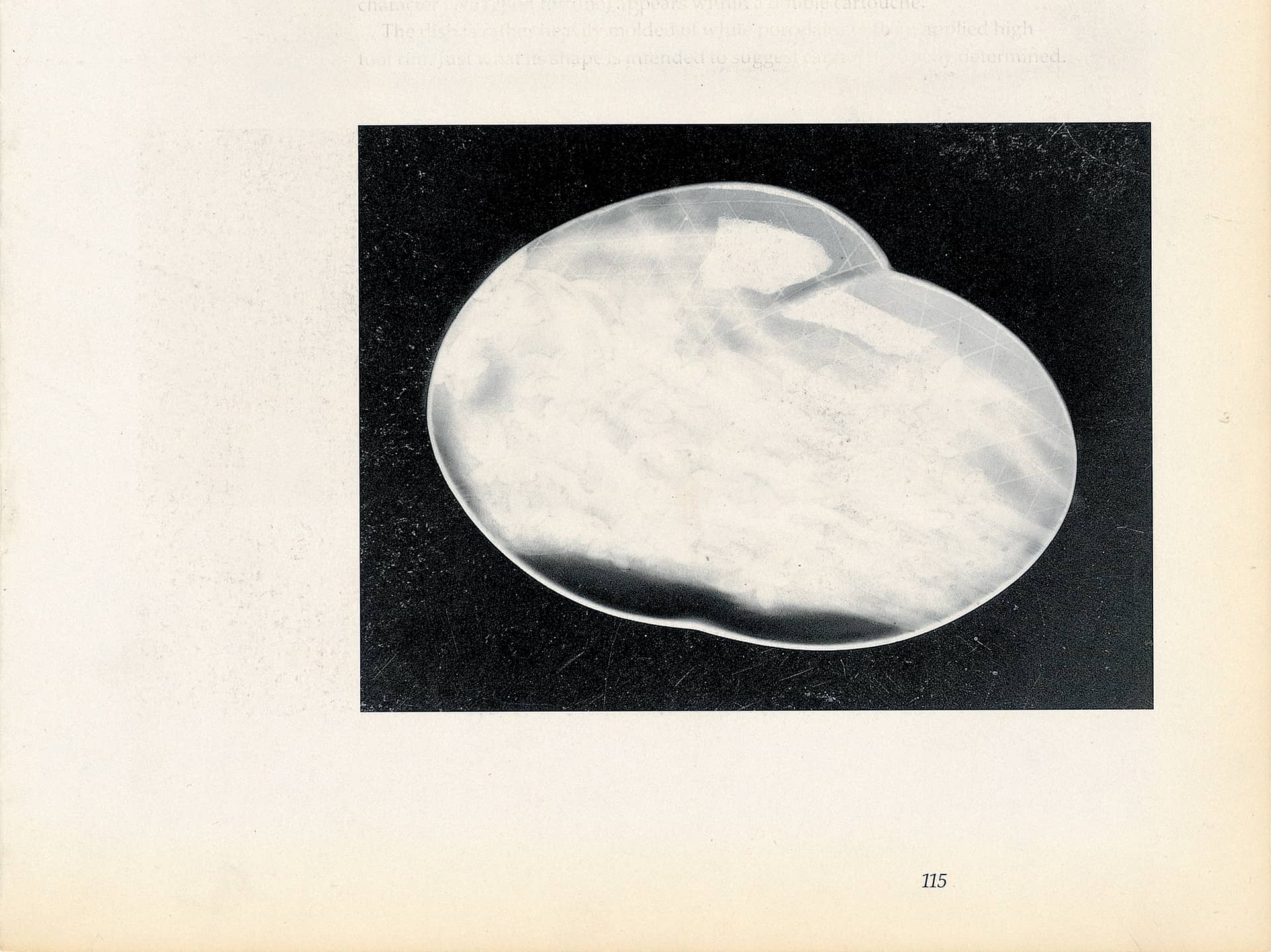

Odili: I start my paintings with drawings made on graph paper, and then I apply the work directly onto the canvas or the wall. Only recently, with the commissioned work, have I started making studies. The drawing itself holds and contains the color, but it is only while I start applying the color that the final shades are determined, and the work takes on a new less predictable direction. Think of watching a river flow over a bed of rocks; the bed of rocks, like the graphs, are like an armature, and the color is like the water. The water moves and circulates based on the structure of the underneath. If the bed of rocks was structured differently, then the water would flow in a different manner, and the colors I chose are also influenced by the structure of the drawing. The works power is derived from this combination of form and color.

___

Odili Donald Odita is an abstract painter whose work explores color both in the figurative historical context and in the sociopolitical sense. Odita has said, “Color in itself has the possibility of mirroring the complexity of the world as much as it has the potential for being distinct. The organization and patterning in the paintings are of my own design. I continue to explore in the paintings a metaphoric ability to address the human condition through pattern, structure and design, as well as for its possibility to trigger memory. The colors I use are personal: they reflect the collection of visions from my travels locally and globally. This is also one of the hardest aspects of my work as I try to derive the colors intuitively, hand-mixing and coordinating them along the way. In my process, I cannot make a color twice – it can only appear to be the same. This aspect is important to me as it highlights the specificity of differences that exist in the world of people and things.” Odita goes on to express his desire to speak positively about Africa and its rich culture through his work.

In recent years, Odita has been commissioned to paint several large-scale wall installations including The United States Mission to the United Nations in New York (2011), the Savannah College of Art and Design (2012), New York Presbyterian Hospital (2012), New Orleans Museum of Art (2011), Kiasma, Helsinki (2011) and the George C. Young Federal Building and Courthouse in Orlando, Florida (2013). Odita has had several solo exhibitions in museums and institutions across the globe including Savannah College of Art and Design; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; Studio Museum in Harlem; Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita; and Princeton University.

Odita was born in 1966 in Enugu, Nigeria and lives and works in Philadelphia. He has been the recipient of a Penny McCall Foundation Grant in 1994, a Joan Mitchell Foundation grant in 2001, and a Louis Comfort Tiffany Grant in 2007. Also in 2007, his large installation Give Me Shelter was featured prominently in the 52nd Venice Biennale exhibition Think With The Senses, Feel With the Mind, curated by Robert Storr. He has been represented at The Jack Shainman Gallery since 2006. Solo exhibitions at the gallery include Velocity of Change (2016), Body & Space (2010), Fusion (2006). He has curated an exhibition at the gallery titled The Color Line (2007) and a solo exhibition, This, That and the Other (2013).