Studio Visit

I recently read an article on the internet that pondered a long list of things technology has to answer for; limited attention spans, the end of artisan craftsmanship, and naked selfie sharing (amongst others). My Iphone fell in the toilet and died when I left it on the ledge while showering. I wanted to be close to it. Sometimes innovation requires a movement backwards, and this is exactly how Luke Ives Pontifell has revolutionized media’s oldest business: Bookmaking. Thornwillow Press has built its name preserving the sensual art of making books by hand, boldly producing large scale print runs of type set, hand bound editions.

I spent two days at Thornwillow Press in Newburgh, sixty miles north of New York City over three years ago, at a time when I was just starting my own publishing company. I initially approached him about printing a book I was working on, but quickly realized just how out of my price range his services were. Everything from his high waisted trousers and suspenders to his frequent invocation of literary English throw back to an era before technology transformed our attention spans and our surroundings into ever changing landscapes of ephemerality.

Founded in 1985, Thornwillow Press quickly grew from a hobby into a distinguished press which has printed important historical volumes ranging from Helmut Kohl’s powerful commencement address at Harvard, where he outlined his vision for a ‘United States of Europe’, to editions by Arthur Schlesinger, and many other historical figures.

His operation eventually grew to straddle three continents, and he consolidated this complex operation into an old coat mill in Newburgh, which is today a very troubled city. Thornwillow’s presence is part of its potential rejuvenation. The city once served as the base for the Continental Army during the American Revolution. A city selected in the 1950’s Life Magazine as one of the most beautiful cities in the country has evolved into a dangerous and economically backwards city in dire need of regeneration. Here is a transcript of our talk.

_____

Ian: I came to meet you after taking classes at The Center For Book Arts. I think you did too. Tell me how you got started.

Luke: When I was in high school I took a letterpress class at the Center for Book Arts in New York. Letterpress is where the ink is applied to the surface of a plate and then pressed into the paper. It’s basically the same technology as Johannes Gutenberg used 500 years ago. I printed a children’s book that was written by a family friend. I sewed it on the kitchen table and carried it to bookstores, hoping that they would sell it. I eventually found two stores in New York City and one in Massachusetts.

Ian: How did this transition from a hobby into a career?

Luke: A family friend, William Shirer, the historian correspondent, joked – he said ‘Oh, you should print something of mine.’ I said ‘oh my goodness that would be wonderful, thank you…When?’ I ended up printing an essay that he wrote on the dropping of the atom bomb, his reminiscences of how the world had changed. I set the type and printed it by hand, sewed the signatures on the kitchen table and carried it to bookstores. Suddenly I was finding that there were a few stores that were interested in distributing our books. Like the early books of Virginia Wolf and the Hogarth Press, they were hand-printed on hand-made paper, each one decorated with different marble papers, and different pace-papers. No two copies were the same.

Every year during college I made one book as a summer project, writing to different authors. I wrote a blind letter to Arthur Schlesinger asking if he had a text that I could print about John F. Kennedy to commemorate the anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination. He sent a manuscript back in the mail. We never spoke, but I went through the same process – setting the type by hand, etc. I rented access to a printing press in Western Massachusetts and during the summer and printed two hundred copies, including a full leather binding.

Ian: Having started my own publishing company – I always have to deal with explaining to people why I would start a business in a domain that is ebbing. Can you tell me about how this developed into a viable business?

Luke: By senior year reached out through the consul in Boston to Helmet Kohl. At that time the Berlin Wall had fallen but Germany had not yet unified. Helmet Kohl came to Harvard to deliver the commencement address, in which he outlined what he hoped would happen in Germany and Europe; that Germany would re-unify and that there would be a United States of Europe. His speech became an outline for the formation of the E.U. and the unification of Germany. I wrote to him and said I’d like to print his speech, and got word from his minions that he would agree to that. We ended up meeting in Cambridge, and agreed to then sign copies of the edition, dating them on the day of Germany unification. That book, as well as the Walter Cronkite book on the moon landing and Arthur Schlesinger’s book on J.F.K. stand as markers for turning points in history. They act as time capsules. The books at that point were either printed by me or were printed at a press up in Vermont where I would go and visit.

What started as a hobby eventually grew into a small business – my poor roommate was stuck stepping over boxes, shipments and deliveries of books – while people were starting to come to work in our dorm room. By the time I graduated it was something that I could possibly see moving forward with.

After graduating, a friend had sent a letter on beautiful hand-made paper, which it turns out was from a mill in the Czech Republic. It was the end of Communism and the beginning of the privatization of all these Eastern European businesses. I was doing some design work for Mont Blanc, the pen company. I was in Hamburg, Germany where they’re located, when I decided to make a side trip to Prague and look for this ancient paper mill. Under Communism, the Czech Republic was a very desperate and sad place. The Russian dominance did horrible things. One of the things though that survived and was done very well was that there was a perpetuation of crafts, hand-craftsmanship and traditional trades – paper-making, bookbinding, and old printing techniques had survived and unexpectedly flourished in that part of the world – in ways that it had not in other parts of Europe and certainly not in America. When I found the ancient paper mill, I simply wanted to be a customer, to buy paper for the books, but it was one of these stories where you couldn’t buy the paper but you could buy the company. So I set the mill up to make paper for our books. Mont Blanc said that if you can make the paper for the books, can you also make writing paper? Naturally, ‘Absolutely’ was the only correct answer. So we set the mill up to make the paper for the books, to make writing paper for Mont Blanc, and that’s how the stationary side of the operation grew and that’s how we were able to finance the operation. Suddenly we were making paper not only for Mont Blanc but also for Cartier, the handmade paper for Cranes, for William Arthur, and for Polo. With a blink we were the largest producer of handmade paper in the world. The joke of course is that if you and I were to start making handmade paper today, we would be the largest producer of handmade paper.

Ian: I find it so amazing how intertwined your businesses development has been with major historical events. Can you tell me a bit about what Post-Soviet life was like?

Luke: We ended up having 50 employees mostly dedicated to hand dipping sheets of paper in giant vats. The first seven were beautiful and idyllic and extraordinary. The second seven were increasingly painful and difficult. All the things they say about doing business in Eastern Europe are sadly true. The corruption, the theft, the immorality of business and fundamentally of the society, I believe, made it impossible to function there. What was not nailed down seemed to just disappear. As we continued to grow, we increasingly needed to find solutions to keep up with our growth. We set up a bindery in England; an hour outside of London, where we were working with a wonderful craftsman who was hand-binding the leather books in North Hampshire. We set up an engraving company in Florida to handle the custom orders for stationary, and invitations and announcements for rush orders that couldn’t be shipped from Europe. And then I blinked and realized that what was truly a very small business had operations in England and in America and in Florida and in the Czech Republic. We were trying to manage this like Pepsi Cola. It became ridiculous for a small operation. I was spending more time on an airplane then I was actually making what I love to do. So, my wife put a compass on the map in our apartment in Manhattan and drew a one-hour radius where we looked in New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania and found at that point Newburgh, NY.

Ian: I noticed on my way here how depressed Newburgh is today. Why was this an obvious choice for you?

Luke: Firstly Newburgh has a very rich history. It is also an hour north of Manhattan on the Hudson River. It is opposite Beacon and the Dia Museum. It is near Storm King, it is near West Point. It is where George Washington lived during the Revolutionary War, where he commanded most of the operations of the war. We found a complex of 19th century brick buildings; enormous spaces that were running for 100 years as a coat factory. Like many businesses in America, the textile industry was shrinking and they were closing down so we were able to buy the building five years ago and began consolidating all of our operations under one roof. What had been a dream for 20 years finally was actually happening. We had the plate making, the typesetting, the design, the letterpress, the engraving – now even envelope making, die-cutting, marble paper making, pace-paper, all of the book binding, all the editorial work – none of this is in the right order [laughs]. We ended up bringing everything together under one roof for the first time. It was a decision we should have done years earlier because now this dream has come true.

an: It is amazing to see a craft that I learned at the Center for Book Arts, being really practiced, and seeing people find employment in it.

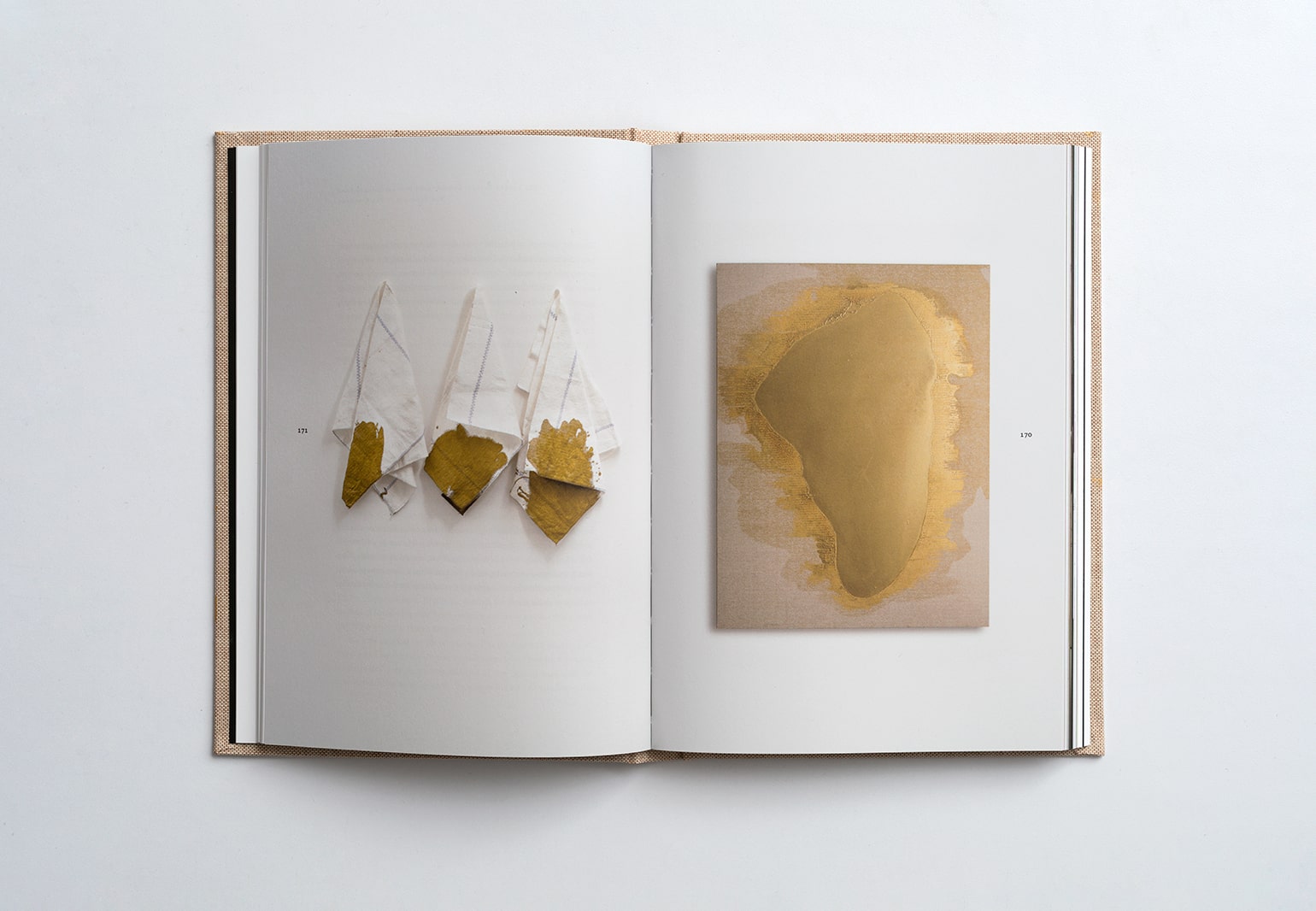

Luke: We’re employing people in artisanal crafts that are as much a way of life as the product that is produced. It’s making things with your hands in this day of disposal and intangible communications. To make books that are beautiful and lasting where the format of the book is part of the experience. The touch of the leather, the smell of the binding, the smell of the ink is part of how you experience the written words on the pages. I argue that, as communications is more and more ephemeral and disposable – -we delete our emails, we hang up the telephone, throw out the newspaper at the end of the day, soon it will be questionable if there are newspapers left at all, we’ll be reading books digitally. All of this is good. All of this is fast, efficient, productive. But all of this makes more relevant the idea of something that is permanent and lasting, that has object quality. The format enhances the relationship between the reader and the text. This applies to books, stationary, a letter, an invitation. What unites all of the work at Thornwillow is the artisanal craftsmanship that somehow ties to the experience of the written word. All of this is part of how we as people communicate. All of this is essential to the preservation and experience of our culture.

Ian: I am curious about what is happening in Newburgh today.

Luke: It’s actually very sad what has happened to Newburgh through corruption, and opportunism. At a certain point it was more economical for a landlord to rent their spaces out to Section 8 housing rather than on the open market. So government subsidiary, in an effort to do something good, ended up undermining the city. People were taking advantage of this situation, of these benefits. Before long neighborhoods fell into complete decay. Rows and rows of beautiful brick houses allowed to just fall apart. In that sense it’s a tragedy. On the other side, I feel it’s not unlike my memories of SoHo when I was a child growing up in Manhattan. Back then, you didn’t walk the streets of SoHo at night – it was dangerous. Or the Upper West Side, if you went up past 96th street . . .that was not a very wonderful place to be. That change is obvious in Manhattan and I think that is what is ahead of us here in Newburgh. There are young artists moving here, who live here. Photographers, painters, sculptures, artisanal craftsman, metal workers, glass blowers all in this neighborhood, in this community, making beautiful things by hand in a world that doesn’t seem as much to appreciate handcraftsmanship. But again, that’s the dichotomy and I think one that makes what we do more relevant and not less relevant.

Ian: This largely contrasts what I have read about the city’s early years…

Luke: Absolutely, but still, the architecture is extraordinary [background interruption] – – it’s one of these great cities beautifully situated on the Hudson River. We were attracted by the architecture certainly, also by its proximity to New York, also by the fact that we were able to find this wonderful building that gives us more space than we need. The idea that we can in fact be here, stay here, and grow here.

Ian: You seem to be really interested in American History – tell me a bit about the book you are working on now.

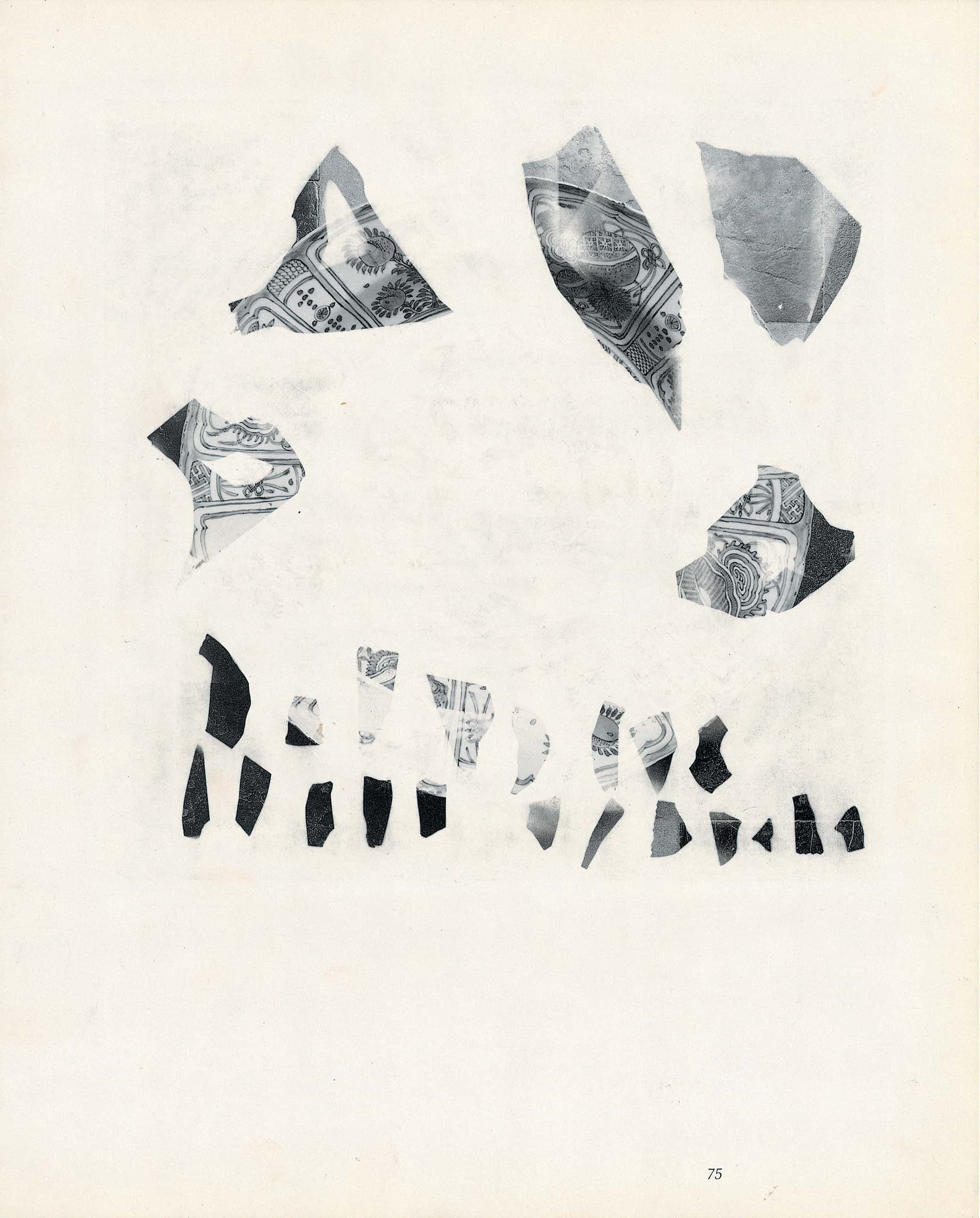

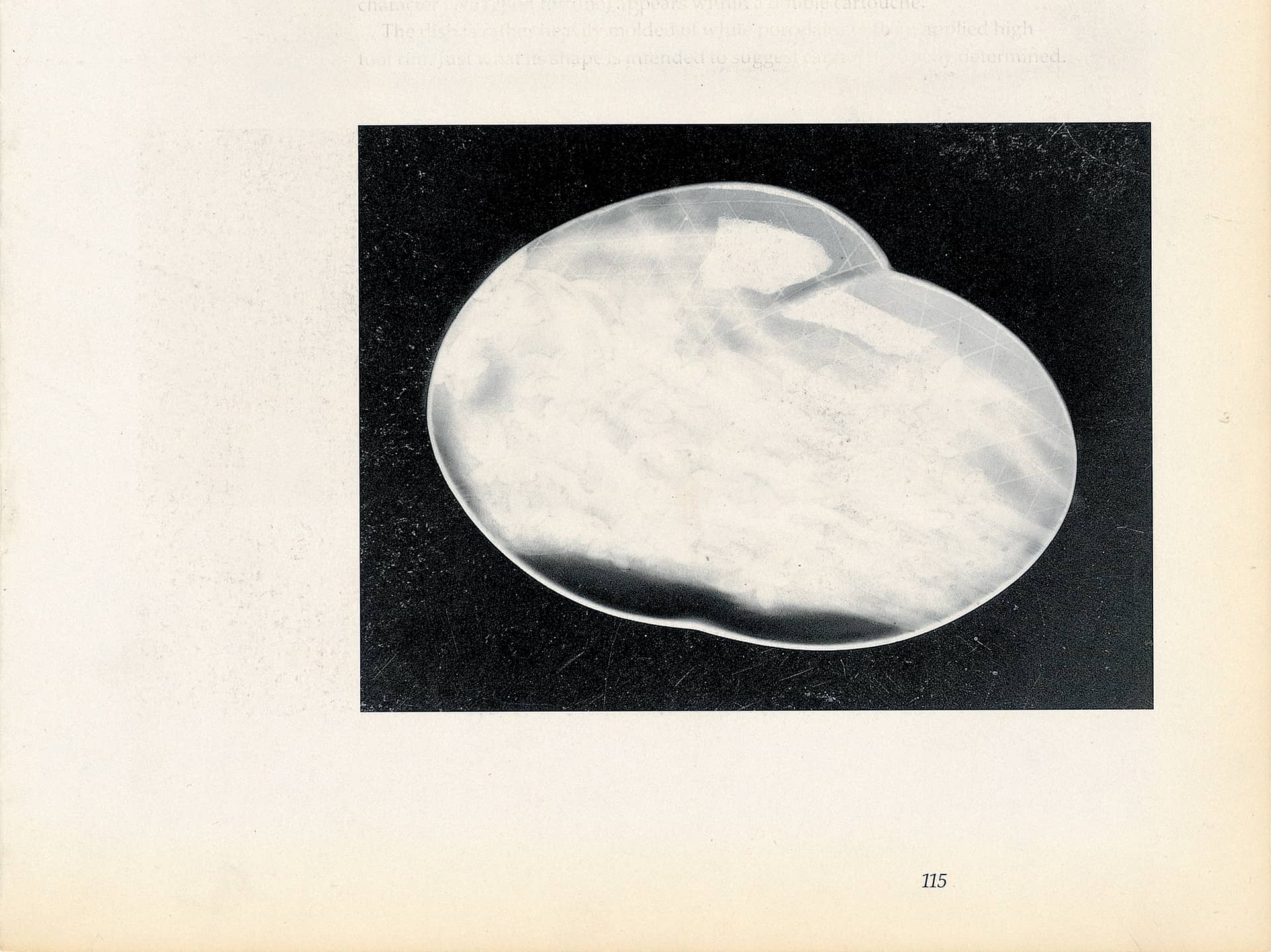

Luke: This edition is the fourth in a series of facsimiles of presidential letters and documents that have been complied by Wendell Garrett, historian and head of the board of Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s house in Virginia. A Professor and a historian, he edited the Adams papers, and collected documents and letters by all of the early American Presidents in transcript and then some of them in facsimile. The cover is done with a gold stamping machine. It heats up and stamps the leather cover of the book with gold leaf. The book is available in two different versions. One in a half-leather binding and then 50 are in a special, full leather binding that is set with an artifact. In the case of the George Washington volume there was a musket ball from a Revolutionary War battlefield in South Carolina. In the case of Adams there was a piece of granite from Adam’s house in Quincy, Massachusetts. In the case of Thomas Jefferson there was a piece of wood from the beams in the ceiling of Monticello. Now in the case of Madison, we have a brick from his home in Virginia, Montpelier. We cut little pieces of brick that are then set into the hole.