-

Interview

MAUD JACQUIN: _a_a_o_ue began with an exhibition catalogue devoted to the Burghley House Collection of antique Japanese porcelains. How did you come across this catalogue, and what attracted you to it in the first place?

KEREN BENBENISTY: I found the catalogue in New York, at Materials for the Arts, a large warehouse with art supplies and materials that artists can come collect for free. My work is centered primarily on drawing, but I’m not bound to any specific medium. I had often worked with found objects and domestic items such as used books and printed ephemera, and when I got to the book section, I realized that these were my “materials for the arts.”

I was as attracted by the catalogue’s reproductions as I was by the round shapes of the porcelain they depicted. Together they created an interesting intersection between an object and its background, which results in an aesthetic that is both formal and nostalgic. Having just moved to New York from Paris, where I had lived for the previous 13 years, I was searching unconsciously for traces of history, for the feel of ancient slabs, paper, ink and glue, for organic materials which eluded the synthetic quality of contemporary objects. New York seemed so new and modern to me that it felt empty. I moved from a nineteenth-century city to a twenty-first century one, and this period of adjustment was reflected through these intuitive choices.

Over time I realized that I was in search of some archeological dimension to New York—an impossible search, since that dimension is always lacking. Coming from Paris, I noticed that here people are much less attached to their objects. They dispose of things quickly, and the life cycle of commodities is accordingly shorter. Second-hand stores are always filled with new, fully-functioning items, especially compared to the “relics” you might come across in Europe. In New York people relate differently to material objects; there is much less intimacy. As a native of Israel, itself a new country, I recognize within this relationship an impulse to erase the past in order to build something new—to precipitate the future, as it were.

MJ: The remarkable thing about these porcelains is that they manifest early points of contact between the Orient and the Occident. They remind me of a fascinating exhibition that is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum, entitled Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500–1800. It retraces the world’s early trade routes, showing how the circulation of textiles along a global network also generated inter-cultural encounters, spreading ideas and techniques. Like the carpets, curtains, and dresses featured in the exhibition, the Burghley House porcelains also attest to a cross-cultural fertilization in the pre-industrial era.

KB: This “circulation of objects” and how we retrace it is very important to me, especially in this current book project. I generally choose objects that encapsulate facets of the East-West dialectic, things that bear the marks of greater circumstances and have history written on them, so to speak. I see them as “cultural objects,” in the sense that they confer the complexity of the intercultural relations from which they emerged. These may be “cultural objects” per se, artworks intended as such, or common everyday objects that are equally able to manifest their greater cultural-historical background.

In the case of the porcelains, the cross-cultural dimension can be read into their decoration. Many of the pieces in the Burghley collection were specifically made in the East for Western export, even as early as the seventeenth century. The decorative patterns enclose a whole political dimension—a “politic of the decorative,” as they were meant to “look” Oriental, to represent the object’s Eastern origin, while the ceramic molding itself followed European designs and stylistic conventions.

MJ: In addition to being products of a cultural exchange, these objects relate the historical fascination of Europeans with all things Oriental. I’m thinking of the popularity of chinoiseries and turqueries in the eighteenth century, or later the pronounced taste of the nineteenth century for Orientalist themes, whether in painters like Delacroix or Gérôme or in post-romantic literature. No doubt, the porcelains in the Burghley House Collection signify exchange and cultural hybridity, but they also speak of the exoticization of the “other,” implying issues of domination and power.

KB: This exoticization of the ‘other’ is janus-faced, already implied by fact that the porcelains were created to suit western tastes for the Orient, and were intended for western export. As objects of an aesthetic exchange between east and west, they both mirror the complexity of the orientalist dialectic, and expose the relations of power which govern this exchange. This ambiguity is partly what led me to erase them—to transform them while leaving my mark on them. The erasing gesture is a way of doubting, of denying what is there. It is also a way of re-imagining them from a contemporary perspective, ostensibly anachronistic to the circumstances of their making, from my own Occidental and Middle Eastern perspective.

When considered through a modern perspective, the Orientalist decorations on the porcelains were asking to be erased—they are redundant, an aberration to the purity of function and form. Modernism strives to purify the object. The modern aesthetic would, to an extent, devalue these art objects—an attitude that I recapitulate in some of the sheets, by clearing the object of its embellishments while leaving the outer contours of the vessels intact.

I should add that by taking such a course of action I have no intention— let alone the possibility—of applying any real transformations to the actual ‘cultural object’ in question, which would amount to changing history. I can only tamper with its documentation through its material reproductions. I am able to interfere with its iconic visual trace in collective memory, as I did with Hokusai’s Great Wave, which I enlarged to the size of a wall with thousands of black fingerprints. The Great Wave too is arguably a case of a double-sided mutual exoticization. In Neil McGregor’s History of the World in 100 Objects, he claims that even this “emblem of timeless Japan” consciously borrows from the West, as the blue used by Hokusai was in fact Persian Blue, an imported substance.

MJ: You talk about re-imagining the object from a contemporary perspective, and indeed it seems that this project is also a way for you to raise questions about the present. Do the categories of Orient and Occident still make sense today? How have the power relations between West and East, both Far and Middle, changed over time, with capitalism, global trade and massive consumerism? Maybe you could talk about Holding Place Holding Place , a work from 2012 which I think is a good example of how you use objects—in that case the Duralex tumbler—to expose the complexity of these relations and the political and economic stakes that underpin cultural exchanges?

KB: Duralex is a modern brand that started producing glasses and tableware in the 1940s. They were extremely popular in France, but today the iconic Duralex tumblers are found mainly in the Middle East, where they are used for serving traditional black coffee. The company almost went bankrupt in the 1990s, but was rebought by Lebanese investors who capitalized on this new-found popularity. The design itself is modern, timeless in a way, and even though the wares are mass-produced, the glass somehow seems chiseled by hand. The tempered glass they are made of lends them an archaic, enduring quality, and the shapes have always reminded me of sacred Oriental architecture. The Duralex tumbler is another example of a ‘cultural object’, in this case a commodity, which encloses a cultural-economic interplay between East and West.

Holding Place is based on pages taken from Israel, the Promised Land, a photo book from the early 1970s which was printed when Israel enjoyed enormous prestige following the Six-Day War. It features atmospheric images of the sacred sites, romantic views depicted in highly saturated colors that glorify the archaic beauty of the land. I stamped each photograph with black coffee using the bottom of a Duralex tumbler, thus tainting images of sacred, immemorial vistas with the profane marks of everyday life. As with my current project, the act of staining and masking serves to mark as much as it does to conceal.

MJ: Let’s go back to the catalogue and to the various transformations that you apply to it. Can you describe your working method and the different stages of that process?

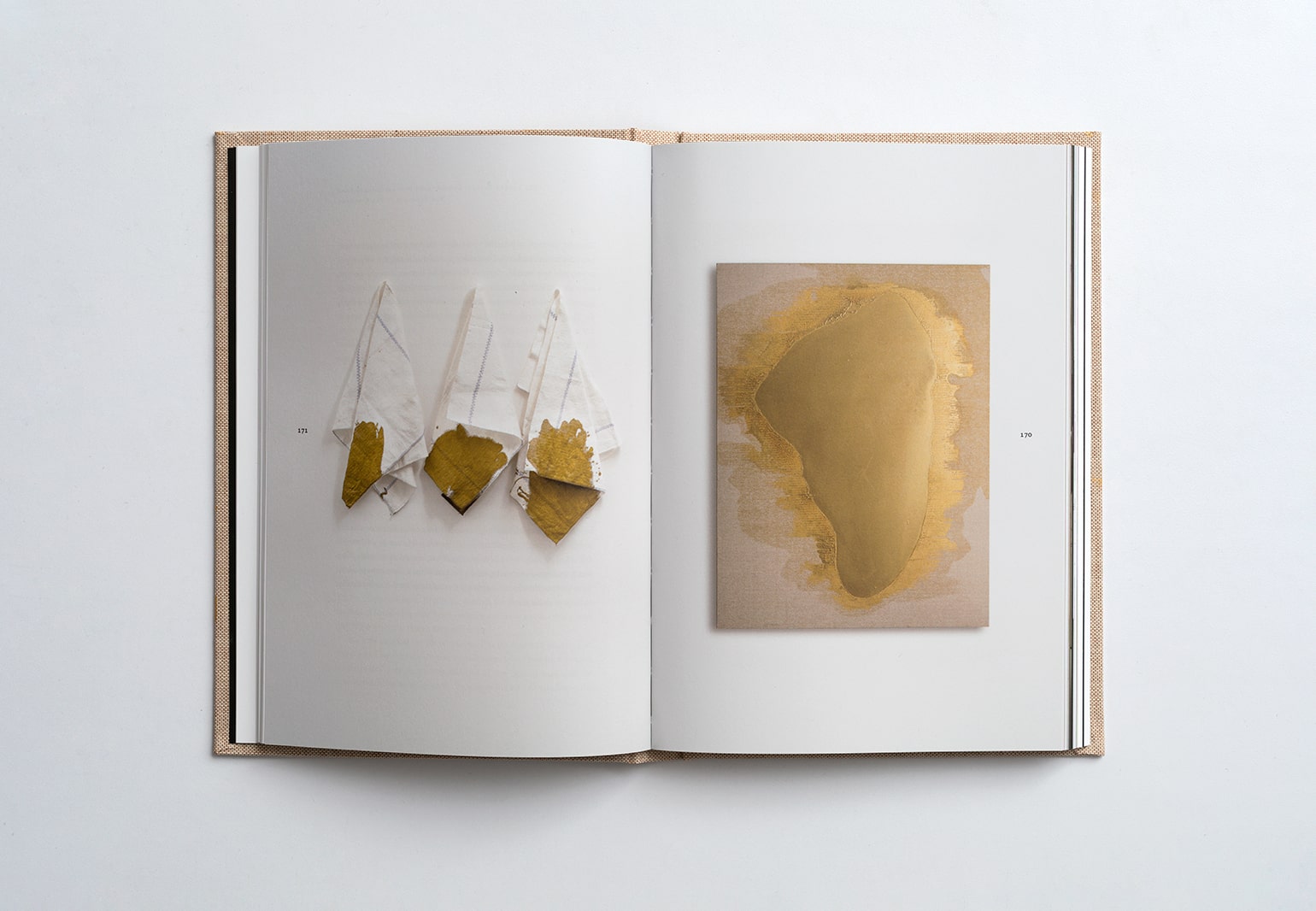

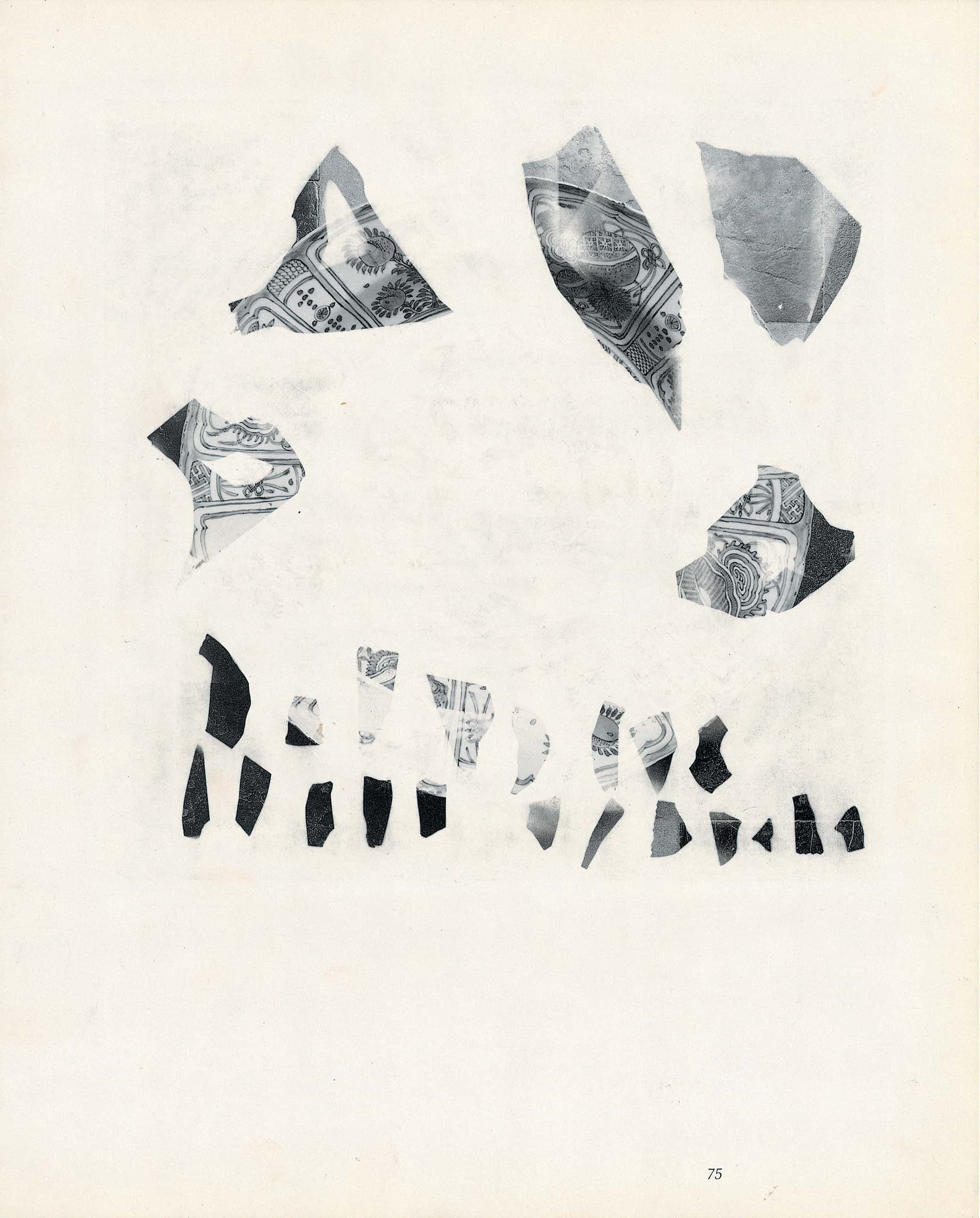

KB: At first I dismantled the catalogue, to work on each page separately. The offset reproductions were erased with a simple rubber eraser according to two different methods that evolved as I went along: first with taped masks, which delimited specific areas of the page intended for erasure, and then freehand. The first process was less intuitive and more complicated, involving drawing, collage, tearing, taping, re-taping. As a masking tool, the tape became the negative space of the drawing as unmasked areas were gradually being erased to reveal the white of the page. The residue of rubber shavings was collected in glass bottles, preserving the offset ink that had been removed.

MJ: At the end of the process you re-assembled the erased pages to physically re-form the original catalogue. Why did you decide to follow the exact order of the original pagination?

KB: Although the work process itself did not follow the original page order, I did set out to preserve the page numbers intact, which allowed me to eventually rebind the book in its original order, sometimes with several variations of the same page number. The identical pagination designates the erased version as a phantom or a trace of the original. Some pages I erased completely, leaving only the page number at the bottom. When a page is removed entirely, a blank white page is inserted to stand as a ‘signifier’ for the missing objects. They give the feeling of a sketchbook where there are always breaks in the sequence, a vacant space surrounding the other drawings.

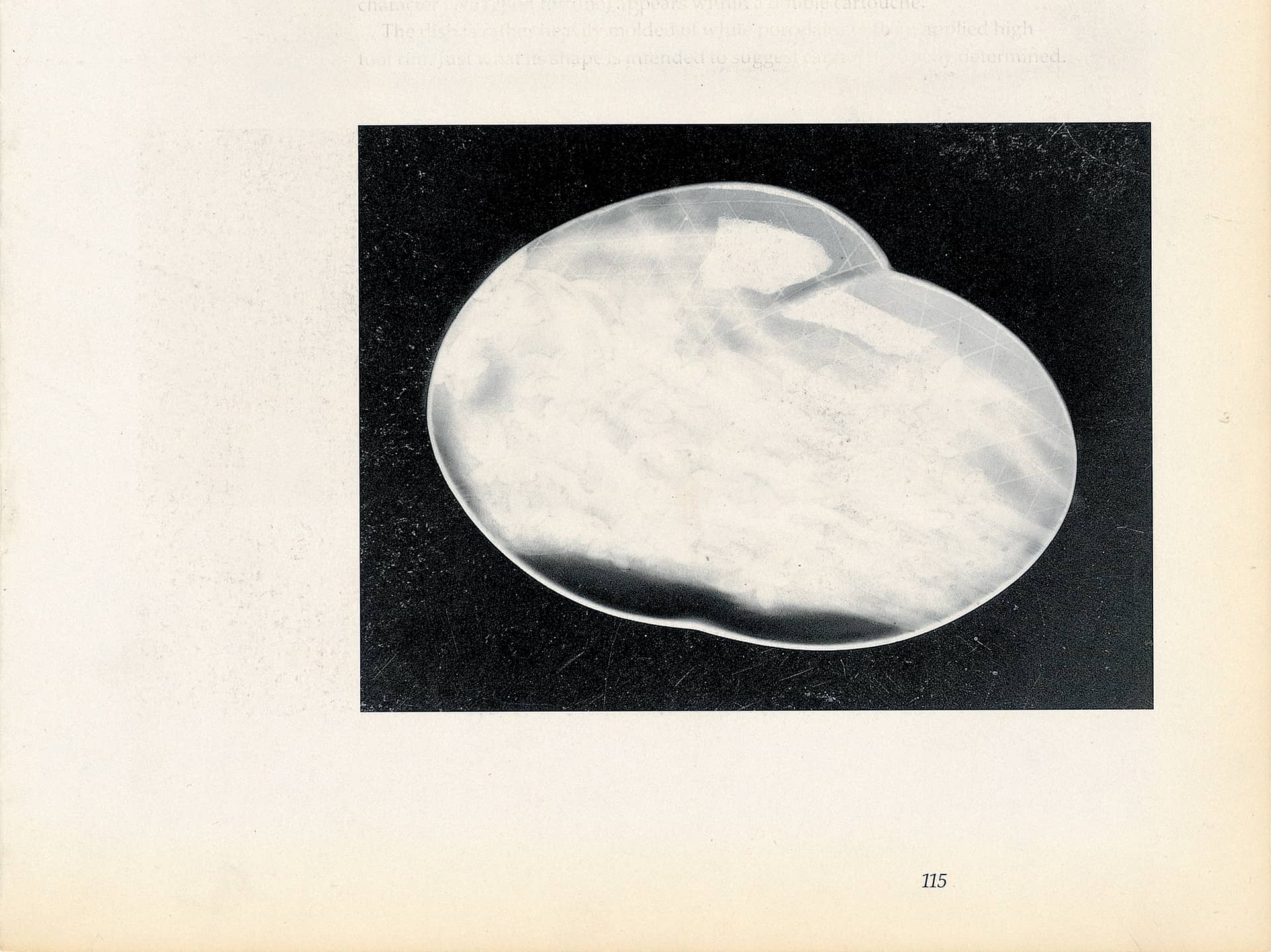

MJ: You speak of two different methods of erasure used within the book, producing two distinct types of images. Some pages evoke the more angular fragments of a broken archeological artifact, while in others you chose to maintain the integrity of the object and rub off all its decorative features, as if the porcelain had been eroded by time.

KB: For the first three months I was drawing fragments. I simply wanted to shatter the form of the objects, without setting specific methods or guidelines for myself. In creating the second group of images you refer to, I targeted the painted ornaments on the porcelains, these miniature figurative stories that each of them carries, which I turned into ghostly, hollowed-out images. In both cases the object itself remained the focus of the gesture rather than its documentation—the “photographic object,” to use Barthes’ terminology.

There was however a third type of treatment that did center on the image, where I had sought to blur the lines between the object and its background. Here the erasure was aimed at unifying them, at blurring the contours between foreground and background and immersing the object in its surrounding page. In all three types of images I essentially tried to strengthen the physicality of the object, to render it more present, to allow it to regain its status as material object.

MJ: You communicate the passage of time in two different ways; one group of images express the slow workings of time by mimicking the patina of aging, whereas the fragments manifest a sudden action, a precise moment of destruction.

KB: That’s an interesting way of seeing it, because the work process itself suggests the opposite. The fragmented images might give the feeling of “a sudden action,” but the process itself was actually time-consuming and laborious, as opposed to the “ghostly” images, the second group of images, which were much easier to accomplish. These are less thought out graphically; they follow the original composition of the page and are quicker to execute. In general, though, the differences between those two approaches reflect changes in my state of mind as I was working, rather than an intended differentiation meant to expose divergent temporalities.

MJ: I’d like to speak about the fragment itself, which refers both towards the past and the future. On the one hand, the fragment connotes nostalgia, loss, and deprivation. On the other, it signifies the end of something and the possibility of change. Linda Nochlin’s book The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity opens with two images that encapsulate this double-sided aspect of the fragment: a drawing by Henry Fuseli that represents an artist mourning the loss of antiquity, and a revolutionary image showing the severed head of an aristocrat.

KB: The term ‘revolution’ was on my mind as I was working on this project, but also long before, when I made One Revolution per Minute (2010), a slide projection where I addressed what I see as a hidden melancholic or romantic dimension to revolution, which we tend to suppress. Revolution traditionally refers to rupture and change, but the etymology of it suggests a cyclical, circular movement, which is how it was used and understood in early modernity. The shift in meaning is attributed to astronomy, where it was used to describe the cyclical movement of celestial bodies. That is how “revolution” came to acquire its modern meaning, from theories that turned humanity’s worldview upside down.

The term ‘revolution’ contains within it both of these temporalities; it is continuously revisiting the past, as in a Nietzschean ‘eternal return,’ while also designating a forward-facing movement aimed at renovation and rupture from the present. This dual sense also characterizes the fragment, a material trace that may result from an abrupt, violent movement aimed at shattering the past, while clearly preserving that past by assuming the aura of a relic. It is this duality that I try to enact and animate through the effacing gesture that I employ. In _a_a_o_ue, the gesture of effacement revisits the chosen “cultural object” in its printed version, making it appear and disappear simultaneously, eventually turning it into a new image. As I said, it is an operation that marks and highlights as much as it erases.

MJ: The fragments also evoke archeology and its methods. The process you employ can be compared to that of an archeologist, who tediously removes layer after layer of dust to unearth artifacts from the past. Rather than reassembling the fragments into a whole, you break the whole into fragments.

KB: There is a similarity in the process, both in terms of the layers of ink that are painstakingly removed and the “manufacturing” of fragments, which point to a reversed archeology or to spurious archeological practice. To put it in another way, in archeology the practitioner tries to recompose the former order of things, to retrace the identity of an object now lost or shattered, whereas I seek to erase it and make it disappear, to the point that it can no longer be identified and connected to its origin. The underlying urge is one of concealment rather than discovery, and the process involves breakage rather than assembly.

The archeological aspects are embedded in a deeper, more psychoanalytic sense: a long and laborious process of ‘excavation’ meant to uncover fragments from a person’s past with the eventual aim of recomposing them. Freud was aware of the parallels between psychoanalysis and archeology, a connection which he discussed in his writings. I am currently reading a book about Freud’s art collection, The Sphinx on the Table by Janine Burke, which addresses this link; Freud made connections between the objects he collected and his theories and case studies, as though he were able to reconnect with ancient Greek mythology and biblical stories through them. There is of course also a political dimension to archeology, how it is manipulated to validate political and territorial claims. This kind of tension is also stored inside objects, or their remaining fragments.

MJ: You talk about fragments as being manufactured, and indeed that relates to a tradition of artists who create rather than appropriate fragments, in visual art as well as in literature. I’m thinking of Rodin, who was not only a collector of objects from classical antiquity but also an inventor of fragments, like in his headless sculpture Iris, Messenger of the Gods; or Ezra Pound’s poem Papyrus, which seems incomplete as an ancient manuscript that has been partially erased.

KB: Yes; from a certain point onward, fragments became cherished and recognized in their own right, as possessing intrinsic beauty. Modernity was concerned with rupture, fragmentation, the unconscious—especially since Dada and Surrealism, but even before that, as in the case of Rodin. There is also the cult of ruins in Romanticism which is rich in nostalgia; but for modernity, a fragment is evocative inasmuch as it hides something, standing for a greater whole that is forever lost and can only be conjectured. This is where the mystery comes from, the sense that fragments reflect the beginning of something rather than its end. It is like a broken dream narrative that awaits completion, but forever remains elusive—in ruins. I strongly relate to that, and the erasure process that I undertake throughout the book is made in that spirit. The creation of fragments expresses the conflicted feelings I have towards these objects, the urge to create together with the urge to destroy.

MJ: I mentioned literature in relation to the project because of the textual fragments you create out of the essays that open the Burghley House catalogue. You carefully erase most of the descriptive text to create what could be compared to a piece of concrete poetry. Did you have this in mind when working on these pages?

KB: Yes, I was influenced by Mallarmé in particular. When I was at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, I studied his later work, in which he explores the relationship between content and form, text and the arrangement of words and spaces on the page. Marcel Broodthaers’s response to Mallarmé was of particular interest to me. He based an artist’s book on Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance), covering parts of the text with black tape. Broodthaers’s intervention, also titled Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (1969), targets the space of the page, the boundaries of the graphic layout.

MJ: This is very interesting. Broodthaers’s gesture exposed the structure of Mallarmé’s poem by rendering it physical. It revealed the page’s fundamental properties by underlining the centrality of the empty space between the lines. Do you think that you are doing something similar?

KB: That’s an intriguing question… When I first thought of Broodthaers’s artist’s book in relation to mine it seemed to me to be opposed, in the sense that he adds material rather than subtracting. I was driven by the surface of the white page, the underlying origin of printed matter, which I wanted first of all to expose, then to use in order to create a new, hybrid image. I was removing ink to go deeper into the white of the page, the bare surface of it, while Broodthaers had added black bands of tape. But seen from a conceptual viewpoint, both actions are concerned with revealing the surface of the page and its limits. Only the procedures are reversed.

MJ: You talk of erasure as a way of creating a new image—erasure as a creative principle. Of course, this makes me think of Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), about which the artist said, “It was nothing destructive. I unwrote that drawing because I was trying to write one with the other end of the pencil that had an eraser.” Jasper Johns used the oxymoron “additive subtraction” to describe this work. Were you thinking of Rauschenberg when you started your project?

KB: Not at all. I feel that American painters are still not part of my artistic vocabulary, of my “baggage”. Very few serve as reference points for me. Broodthaers’s poetic, minimal and ephemeral gestures are much more impactful to me than the highly masculine, over-the-top, physical actions of American pop and abstract expressionism. That said, at a later stage in the work I did think of Rauschenberg as well, of his White Painting (seven panel) (1951), while his Erased de Kooning Drawing is one of my favorites among his works.

I’d like to stress some differences though. Rauschenberg undertakes to erase a veritable, valuable work of art, while I not only erase a catalogue that is mass produced, but also one that depicts decorative objects which are classified as arts mineurs—which I then transform into a series of one-off conceptual minimalist drawings. Rauschenberg was of a younger generation than de Kooning, who was among the fathers of abstract-expressionist painting in America. By erasing a de Kooning, he was literally erasing history, his own genealogy even, to reinvent a new one. And as we know, he eventually became a pop artist.

MJ: That is true. But don’t you think there is something similar in the ambivalence of your gesture? For Rauschenberg, the act of erasing was both an homage to de Kooning and an iconoclastic attack. It was a gesture of both identification and rejection.

KB: Indeed. The same ambiguity can be found here as well. On the one hand, I aim for a tabula rasa—erasing the ornaments as a way of criticizing, of trying to relocate the relation between East and West. At the same time, my gesture is also made in admiration of the slow, studious and manual production process that these ceramics attest to. To an extent, the erasure itself follows this type of non-mechanized production, where the hand of the artist or the artisan leaves its singular trace on the object. In this sense this project reflects my artistic project at large, confronting minimalism and conceptualism with what appears to be their antithesis—romanticism.

MJ: Yes, you could have manipulated the images digitally, but instead you chose to spend months erasing page after page of an original catalogue. In addition, you kept the leftover erasure shavings in a series of small bottles, probably as way of making visible the time and effort that you put into this process. Your work frequently involves tedious and time-consuming processes. Why is that?

KB: There’s a great difference between time-consuming processes and quick ones, which I have also used elsewhere in my work for different ends. A lot can happen during a lengthy work process, especially in this kind of project where forms are gradually evolving and taking shape on the page, a bit like in painting. When you use digital editing, any mistake can be immediately corrected, often also in retrospect. As a principle, you cannot go wrong. But concrete matter has different exigencies.

In this sense, erasure is very much like stone carving, which is also a technique that I use in my work, recreating Nespresso coffee machines as small-scale ancient monuments. Here too there’s no way of going back; any matter that has been shaved off is removed for good and cannot be re-attached to the main piece. That’s why stone carving requires such experience and expertise. In the case of drawing and erasure, however, you can play with chance and contingency. If I erased too much there was a new, unexpected form to reckon with, a new way of considering the composition on the page.

This type of work touches on the contrast between the unique and mass-produced, which is very important to me. Andy Warhol’s factory remains an inescapable reference here. What I’m doing is likewise repetitive and monotonous, yet I’m also trying to produce something unique, to avoid this semblance of mass-production. Many aspects of my work can be regarded in just that way, as anti-pop. The sixteen bottles that hold the ink residue certainly relate to the temporal dimension of a slow, non-mechanized work process. In a way, they are like hourglasses that measure the duration of the work, holding the ashes of bygone images.

MJ You are interested in the passage from mass-produced to unique handmade objects, which in this work is also a passage from photography as a reproducible art form to drawing. This project has been discussed in relation to photography and I should mention that you won a grant from the Shpilman Institute for Photography. Yet still you insist, like Rauschenberg, that _a_a_o_ue tells us something about drawing. Can you explain why?

KB: I take an oppositional approach with regard to traditional drawing, subtracting ink from the pages rather than leaving marks of ink on it. The movement runs backwards, which brings me back to the idea of revolution in the sense of renewal.

MJ: It is interesting to think about the entanglements of erasure and renewal in the context of the East-West dichotomy that your project addresses. At the risk of sounding cliché, I would say that the concepts of erasure and renewal are more embedded in Asian cultures than they are in ours. We see that, for instance, in the tradition of dismantling the Japanese Shinto shrines every twenty years and reconstructing them anew. Whereas Eastern cultures seem to emphasize impermanence and renewal, the Western world promotes preservation and continuity.

KB: To a degree, the East too preserves its ancient objects and monuments. But I agree that there’s probably a different approach to time in Western cultures, something that I’ve become increasingly aware of since moving to New York, with its consumerist culture of disposable products and obsolescence. Capitalism seems to emphasize the linear time axis, and that’s perhaps a feature of modernity at large. But the cyclical motion is still there, hidden under the surface—and that’s something that I constantly deal with in my work, this notion of the eternal return which manifests itself in the latent and unconscious layers of modernity.

The eternal return of past figures is something that I locate in the recurrence and transmutation of archaic forms; I am constantly trying to pursue and rework this hidden cyclicality through them: the Duralex glass that I’ve mentioned earlier, as well as the Nespresso coffee machines, whose elegant curves evoke ancient sacred architecture and burial sites. I want to bring back the archaic through popular profane objects, to bring forth sacred forms that reappear under a contemporary guise.

The very fact of reprinting the book while closely following its original format also manifests the same concept of return. The catalogue has been deconstructed, erased, and will then be reprinted, rebound and republished with a whole new series of imagery. As per the Eastern culture of renewal, it is interesting to note that the Nietzschean concept is borrowed from Indian philosophy and ancient Egyptian thought.

MJ: There also seems to be a different relationship to the void or to blank space in East Asian cultures than in the West, most notably in the pictorial traditions. In traditional Chinese or Japanese landscape painting, the center of the composition is often empty and the forms disappear in an enveloping mist. In the West, the composition is centered and the contours of forms are enhanced to give weight and substance to the representation. What do the white spaces in _a_a_o_ue mean for you?

KB: When I first started this project I was in search of white space, of blankness, of the origin of printed matter and the beginning of the artistic gesture, the moment before anything at all inscribes itself on the page. I was in search of a void—in its metaphysical sense even, that of the non-being that precedes being. Hence the effaced page signifies for me both a beginning and an end, with the two tied together in indeterminate relations of cyclicality.

MJ: So for you, erasing has to do with going back to some sort of origin prior to the act of creation. I see it more in relation to Gilles Deleuze’s idea that there is never a blank page because it is always charged with clichés. For him, creating does not mean inventing from nothing but actually erasing the common view and tearing a new image out of the cliché. In his own words, “the painter does not paint on a virgin canvas, the writer does not write on a blank page, but the page or the canvas are already covered over pre-existing, pre-established clichés (habits of sight and habits of thought). The clichés must be scraped away to find a singular vital space of possibility.”

KB: I didn’t know Deleuze’s ideas about the blank page and the relation he makes with the erasing gesture… and I like the idea of ending our conversation with the notion of blank space as a vital space of possibility.

MJ: It’s a nice way to end, indeed.

Flesh and Spirit was written by Asher Ginsberg at the turn of the 20th century. I fell in love with this essay the first time I read it, because if the simple precepts it forwards were applied to the way we viewed our own mortality today, there would be groundbreaking implications on the way we relate to the environment, to politics, and to social justice. At the time it was written, the essay pointed to the rivalry between ancient Judaism’s conception of immortality and the growing political materialism that started to emerge at the time of the Roman invasion. As opposed to Christianity and Islam, Ancient Jewish Philosophy conceived of the afterlife as the state of the communities that we leave behind. He(2) did this as a method of countering Herzl’s political Zionist objectives with an alternative vision for the future Jewish State of Israel.

-

Related Images

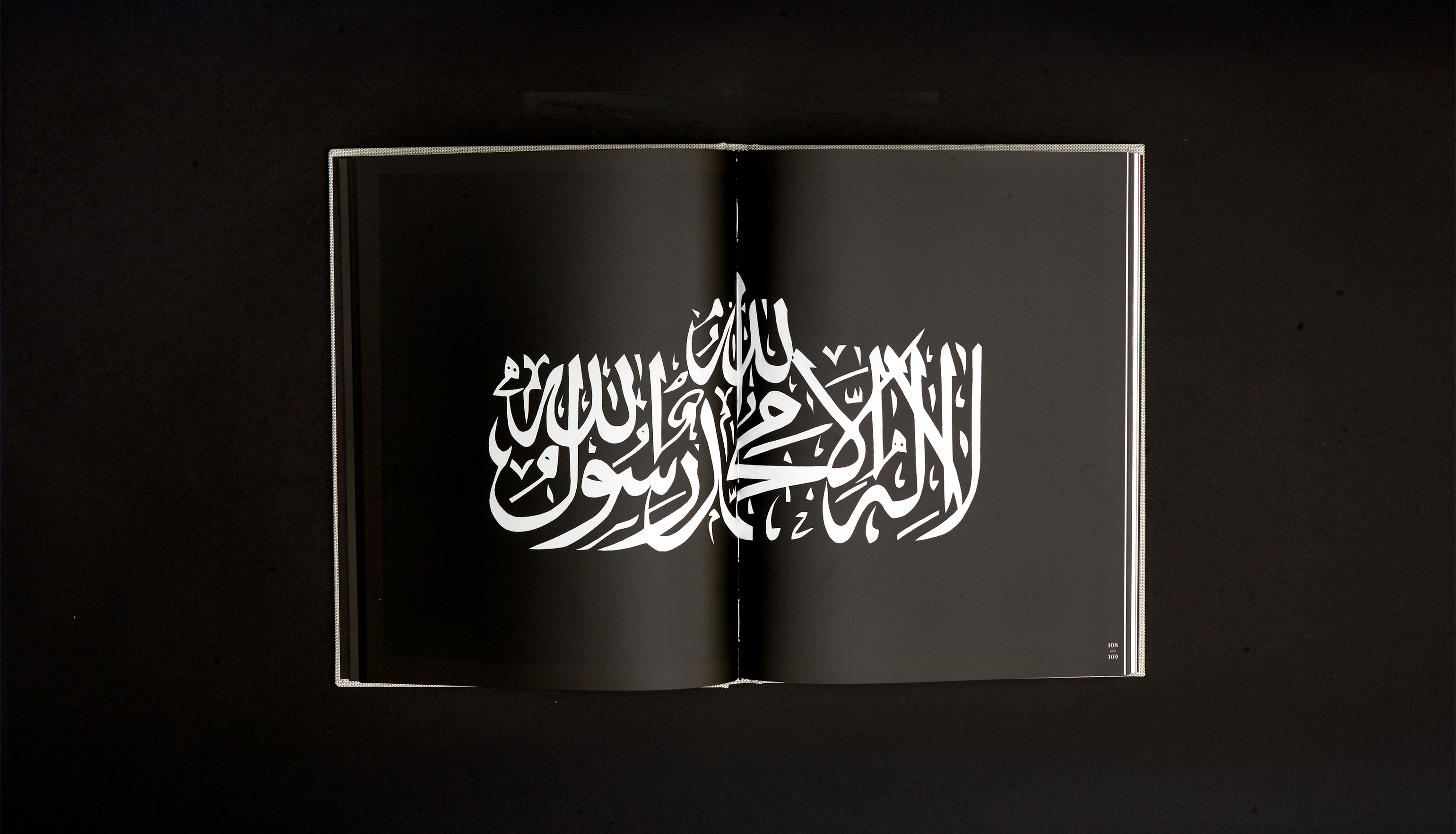

A Spread from ‘A A O UE’

Nespresso, Courtesy of the Artist.

Keren Benbenisty, ‘Holding Place’, 2012, Series of 40 offset prints, Coffee stains, prints of Duralex glassware on Offset prints from a found book “Israel, The Promised Land”, 14`½ x 11` inch – 29 x 36 cm, float in frame. Courtesy the artist.

Venice Biennale For Architecture, Artis, The Jack Shainman Gallery, Printed Matter Art Book Fair, Alon Segev Gallery, Chelouche Gallery, Braverman Gallery, UMapped.