Donald Rothfeld recently bequeathed his entire collection of Israeli Art to the American university, including 161 artworks, and 10 videos, where it will be permanently housed. To mark the occasion, Sternthal Books was commissioned to create a publication which would both present and re-interpret the collection.

Donald with his wife, in front of a peice by Rona Yefman, NYC, 2013, Photograph by Gil Lavi.

Donald with his wife, in front of a peice by Rona Yefman, NYC, 2013, Photograph by Gil Lavi.

IS: Tell me about your childhood.

DR: I grew up in Hillside, Jersey in a heavily Jewish neighbourhood. There was a great deal of anti-Semitism in our neighbourhood, especially after football games on Saturdays. I was raised in a firmly Jewish home. My father was a business man but was a really a closeted Talmudist. I remember on Saturdays he would sit with different tractates in front of him, looking up things in the Talmud.

IS: So your childhood affirmed Judaism as an important part of your identity?

DR: I’ve always said, I do not know what I would be if I were not Jewish. I think one of the biggest turning points of my life was the 1967 war. Up until that time, like most Americans, I harbouring a ghetto attitude. There was a great deal of anti-Semitism in America, and we were afraid to make waves. When the Six Day War happened, I was a physicIS in the navy, and I became a totally different person. I lost that ghetto attitude. I wasn’t afraid to open my mouth. If a Jew was in trouble in the New York Times, I didn’t care, and I still don’t. And that was a very big change; Israel changed me in a very remarkable way.

IS: When was the first time you travelled to Israel?

DR: I first went on a synagogue trip, in the early 1970’s, right after the Yom Kippur War. Nobody was going to Israel, and the country welcomed us with open arms. I then went on several Federation CJA missions, as well as for my sons Bar-Mitzvah, but then eventually I started to go to Israel just to look at the art and vacation and so on.

IS: What was your exposure to art as a child, did it figure at all into your childhood?

DR: I had little exposure to art growing up. I’m a musician, a classical and jazz pianist; music is my first love. I started getting involved in art when I was in the military. My late wife read an article in Vogue about Soho, and she suggested that we check out the scene they were creating when we moved back to the city. It was a level playing field, because neither of us knew anything about it, and as a newly married couple we thought it would be a nice way to grow into our marriage. So I started going to Soho. I’d walk into these shows, and I had no idea what I was looking at. There were four to five galleries at that time; I remember Sonnabend had a show where a man on a horse was walking around in a knight’s outfit. Both the man and horse were staring at me. I’m in this claustrophobic room, and it was frightening, and I don’t scare easily. I quickly exited, and began to wonder what I was getting myself into? I didn’t reject it what I saw, but began to wonder what I was missing. I think that is one of the key elements to being an art collector. We started collecting basically blue chip artists, because that’s all we knew. We bought a large Helen Frankenthaler, there was some Stella work, St-Francis, etc. By the mid 1970’s I grew totally turned off with the art world. I started to read about the shenanigans that went on; the bidding at the auction houses, about people dumping art when one of their artists was having a museum show, and so on. I remember being called by somebody wanting me to get into an art consortium to buy up an artists work so we could control the market. I grew disgusted. A few years later I was invited to a dinner party, and there was a presentation by an art collector from Philadelphia who had this gigantic collection of Soho artists. He would stay in the artist’s loft on weekends, and he was a voracious buyer. He would buy five, six, eight works at a time, and he got me very excited. I started going to Soho with a friend every Thursday, on my afternoon off, and he’d teach me how to look at art. He’d take me up to his studio, and tell me how to analyze paintings, to look formally at them.

IS: What do you think propels people to collect?

DR: The first thing is, you don’t collect with your ears, but with your eyes. You don’t listen to people and say that they have that one so I should get it; you collect according to your own perspective. I have read a lot about what makes a ‘collector’, and I think it comes down to a certain kind of personality, an inquisitive quality. Part of it is the hunt, looking for what you want to buy or acquire, part of it is the respect you get when you one certain artworks, that gives collectors a kind of satisfaction. For me the most thrilling part is engaging with the artists, talking to them, getting into their heads, finding out what propels them. I enjoy asking them formal questions about their work. It was an intellectual need I had, that they fulfilled.

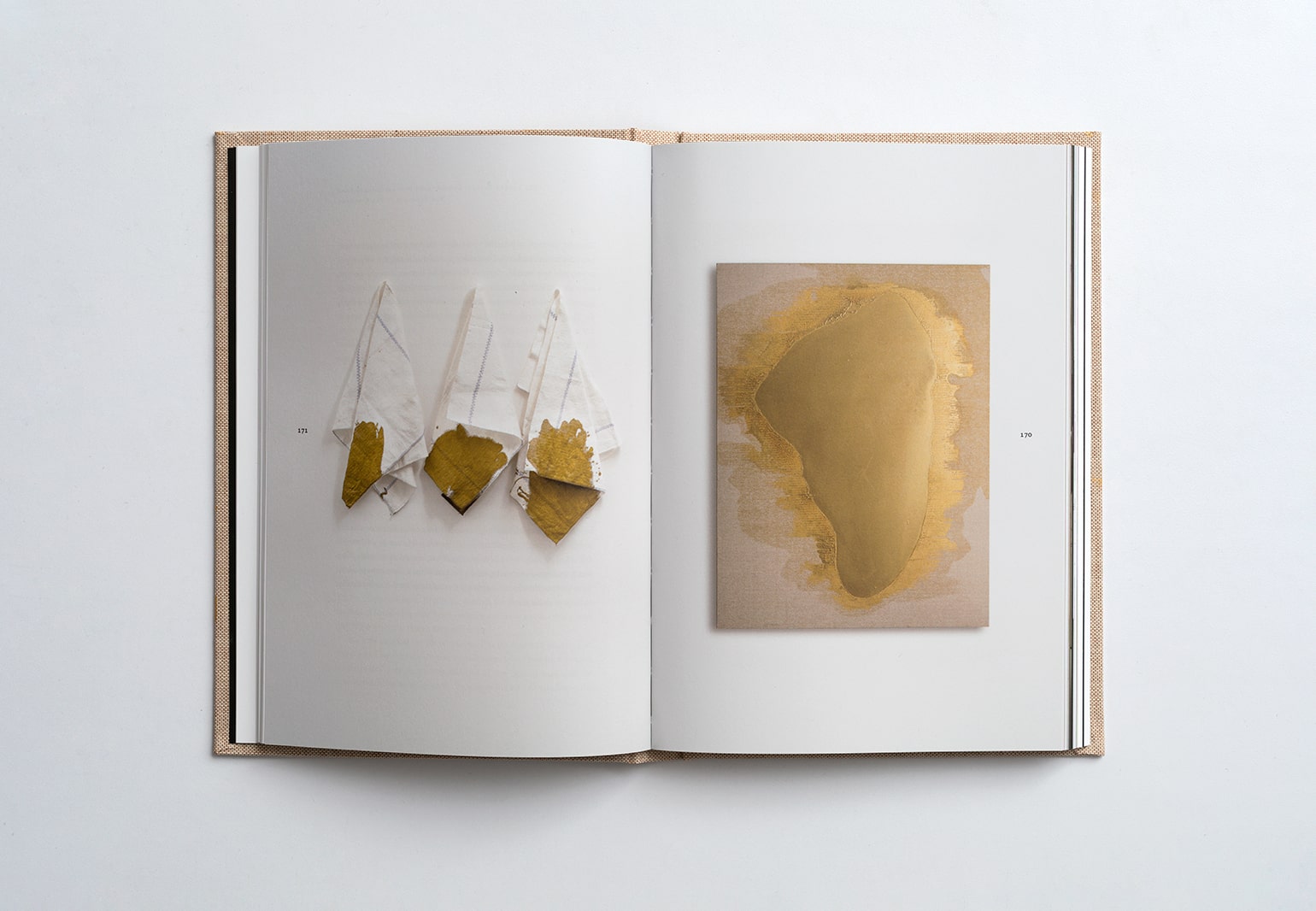

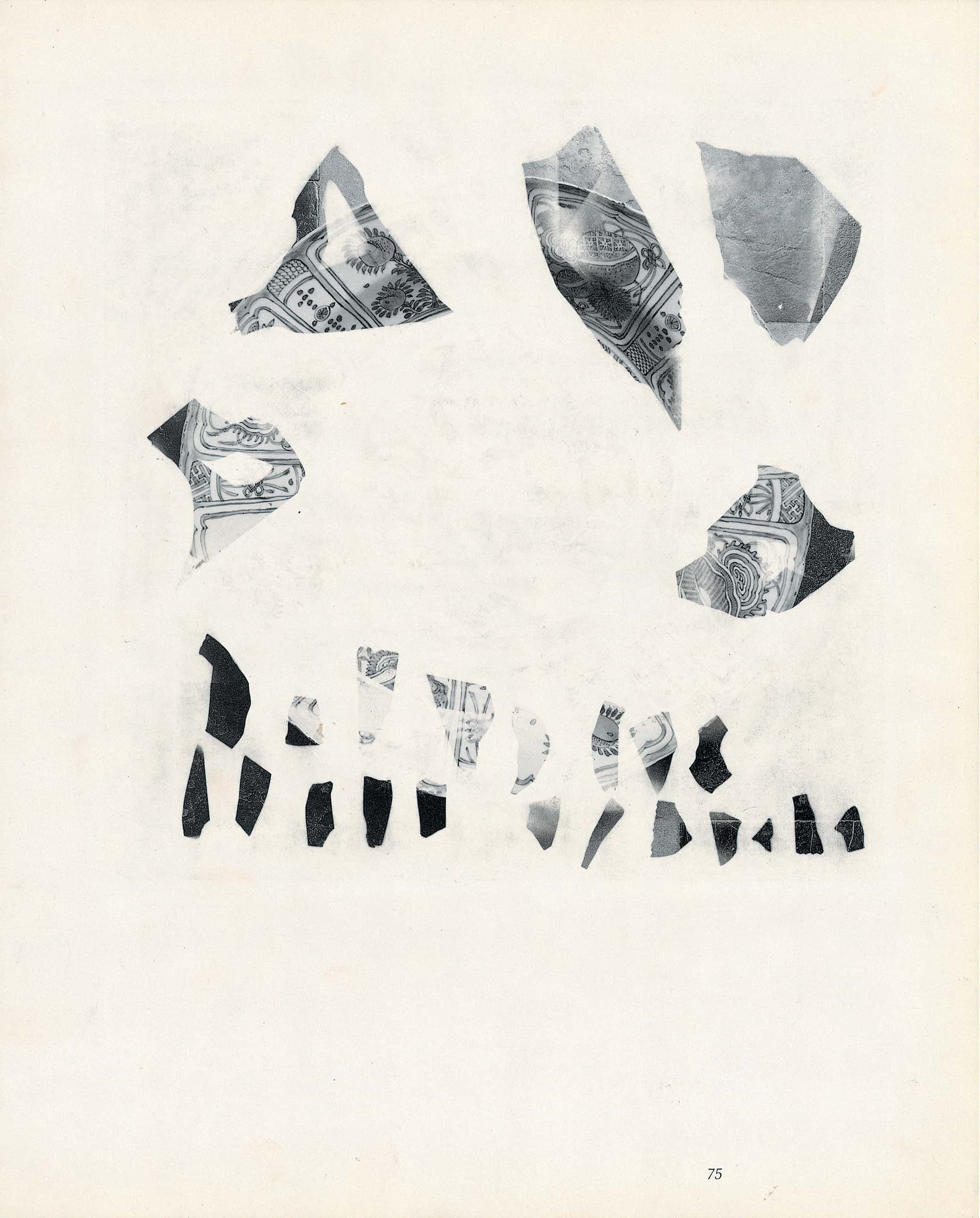

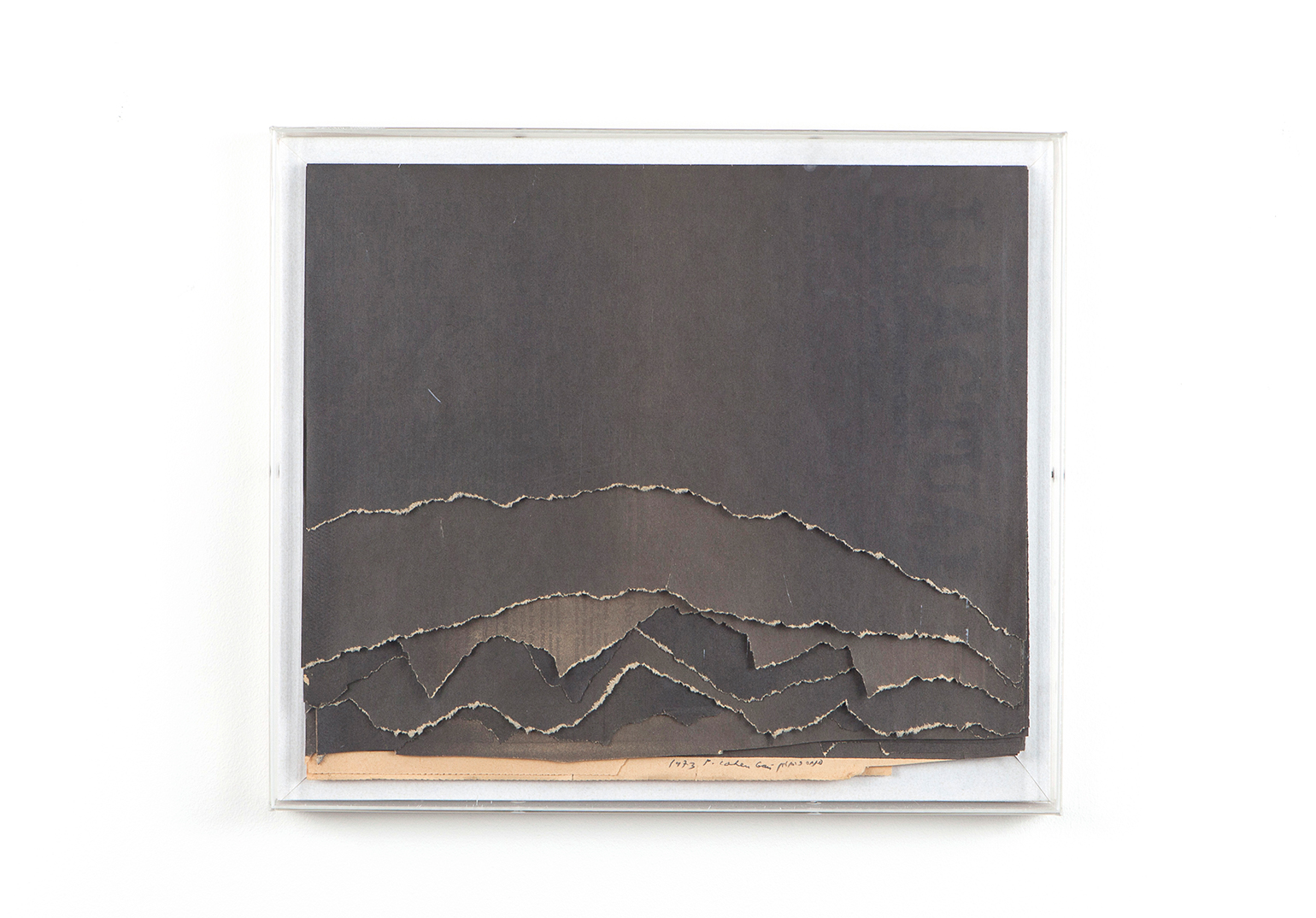

Pinchas Cohen Gan, Mixed Media, 1970’s.

Pinchas Cohen Gan, Mixed Media, 1970’s.

IS: What opened your eyes to what was going on with the art scene in Israel?

DR: In the mid 1980’s I visited the Bertha Urdang Gallery. I knew that she showed Israeli art, but until that time I thought Israeli art consisted of pictures of dancing rabbis that I had seen at synagogue fundraisers. When I walked into Bertha’s gallery, I was astounded by what I saw. I didn’t know they were doing it! This was the mid eighties, and they were very strong in conceptual work, there was a lot of Arte Povera, painting, there was a minimalist sculpture that was stunning. She showed me some pieces by Micha Ullman and Nachum Tevet. She opened up my eyes to a wonderful world that I knew nothing about.

IS: What was the first thing she said to you?

DR: The first thing she said to me as I walked into the gallery was ‘My husband was killed in the 1948 War, and I had to raise my three daughters by myself.’ As an American Jew you always feel that the Israelis gave their lives while we just gave the money, so she got right to my heart. I came back many times to talk to her about Israel art and she taught me, she was head to toe Israeli art. She was very abrasive, with a chutzpah that was beyond description, and she used four letter words more than I would, but she was phenomenal with her analogies, she was passionate, and she got me involved. From then on, I started to go to Israel on art trips to visit galleries and do studio visits. I still go on an annual basis. From day one Bertha wanted me to purchase works by Moshe Kupferman. She brought the works out, and I didn’t get it. Mind you, I’d been looking at art for fifteen years, but I just didn’t get it. It was too dense for me. I said, ‘Bertha, why are there so many layers in his work?’ and she said, ‘he’s digging into the canvas, he’s looking into his family. He lost his entire family in the Holocaust, he’s searching, he’s looking, trying to find them.” Kupferman signs his paintings multiple times, in Hebrew and in English. I wanted to know why. She interpreted this as his way of asserting his existence. The more I look at the works, the more I think she’s right. She kept saying to me, you have to get a Kupferman, and I kept looking. It was very much like when I first looked at De Kooning. I had a lot of trouble with De Kooning, and then finally one day I saw a De Kooning, where I saw the scaffolding of the painting and I got it. I bought my first Kupferman during the first Gulf War in 1991. I was near Madison Avenue, near her gallery, and I heard someone say ‘They’re landing scud missiles near Tel Aviv!” I got so excited I ran into the gallery, and I said ‘Bertha, I want to buy a Kupferman!’ Like that, irrational. That was the first one, and since then, I have purchased twenty-six works by Kupferman, so he got to me. And she said, ‘once you buy one, you will buy many.’ And she was right.

IS: Here I am, sitting in your apartment in front of two photographs by Pavel Wolberg. One depicts a Palestinian women pleading with soldiers in a tank, and the other shows men behind barbed wire. You describe yourself as a Zionist, you’re involved with Federation; does collecting this kind of politically critical art change your perspective on Israeli politics?

DR: Most of the artists I know are left-wing. Though I’m not particularly Left, I don’t see any conflict between my own beliefs and the works I purchase. There are some anti-war statements here, and I myself wish there was no more war, but I’m more to the center. I would not say that the artists have swayed my political affinities, though they have tried to! {Laughs}

IS: Tell me about some of your favourite works.

DR: The photograph Crazy Tree by Tal Shochat is a very striking example. She places artificial pink wallpaper behind an olive tree. I think she’s dealing with the demise of the original Zionistic impulse. The original pioneers were always associated with orange trees, lemon groves, and so on. For me, the background represents the building of Israel, the massive amount of construction, which has come at the expense of this poor tree, which looks like it’s dying. It’s a very powerful image. Looking at it makes me feel both sadness, and a sense of pride. The transformation of the country is in many ways a miracle. Dark Ages is an oil painting by Shay Kun, which also stands out in my memory. I was in his studio, and it was on the floor, and I looked at it and I asked him why there was so much smoke in the sky. The image portrays the view from a car, with rain pouring on the windshield. He explained to me that the smoke was in fact the horizon of trees that lined one side of the road. It’s a very powerful image, with many diagonal perspectives. I asked him what the work was all about. In a previous conversation he told me that his father was a camp survivor, and he described what a road looked like to the one of the camps. I asked him what camp was he in, and how he survived. He told me that his fathers’ job was to cremate the bodies in the ovens. He kind of denied the connection, but the relationship between the painting and his own biography was apparent. I didn’t want to push him, so I dropped it.

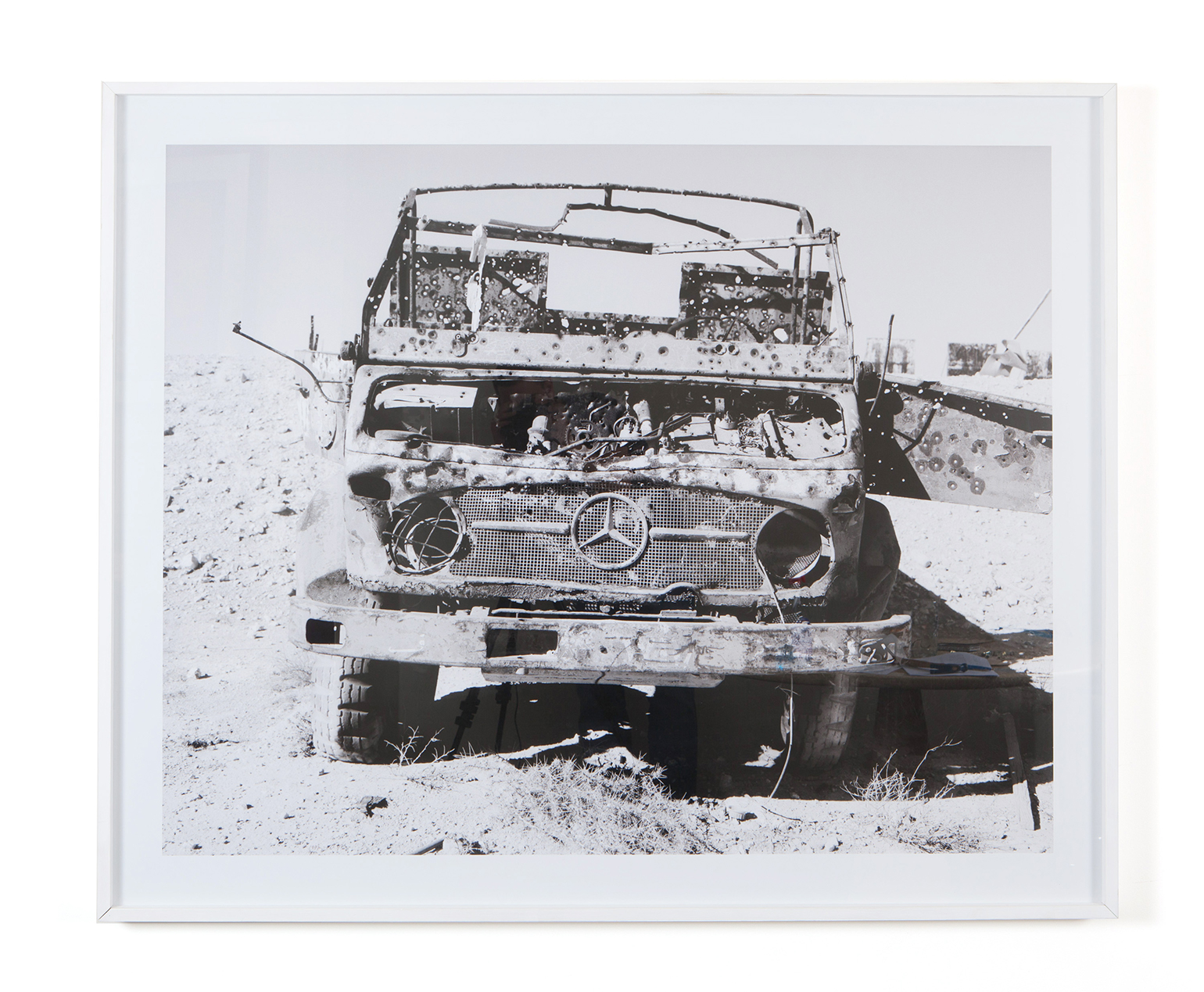

IS: Tell me about the image Burned field after a Missile Attack on Maghar, 2006 by Shai Kremer.

DR: Shai is very interesting photographer. The image is from a series is called ‘Infected Landscapes’ photographed in Israel. At a first glance his landscapes look very beautiful, but when you look more closely there’s always a disturbing element: Either tracks from a tank, or images of fake Arab villages that are used for IDF training. This particular photograph shows what looks like a beautiful golden haze, reminiscent of a September afternoon on the east coast, where around four o’clock everything looks golden. But when you look in the foreground you see some smoke: A katyusha rocket had just landed from Lebanon.

IS: Israeli art has recently gotten a lot more international attention. Why do you think that is?

DR: I think the interesting thing about Israeli Contemporary art is that since the 90’s, the Israeli’s really seem to have found their artistic voice, on the international stage. Up until that time, I feel they were looking to Europe and looking to America. As I mentioned before, I myself have many minimal works from the 70’s and 80’s, but there is something exciting about the young generation of artists, and how unique their vision is. For many years Israel was being built, and the nation was focused on establishing itself. Ideology was strong. Now that it firmly exists, and even has begun to prosper, I think the artists are asking important questions about what Israeli has become, and in which direction it should head. I think that’s why they’re so good now. I think that is why they have such a powerful voice on the world stage.

IS: Can you talk about why you decided to bestow the work to the American university and not a Jewish institution?

DR: I did not want to give them to a Jewish institution; we have been in enough ghettos that art does not need to be another ghetto. These artists need to get out into the world and compete with everybody else. So I decided to look for a university that had a program that might fit my needs. The Katzen Center at the American University in Washington is committed to incorporating the work into the curriculum. We’re going to have a show at the American University in the fall, and most of the work will be up, including most of the videos. My hope is that people will add to the collection. I do hope the work is loaned out. I’d like this to be a forum for Israeli art. I would also like to see Arab-Israeli artists included in the collection.

IS: One of the biggest issues I’ve seen working myself with Israeli artists, they’re often fetishized; they’ll be loved or hated.

DR: Unfortunately it’s very hard for them. They are constantly classified as being Israeli, and that comes with a lot of baggage. I don’t think it will be easy to get beyond that until there’s a resolution in the Middle East. I think the stigma only really transcended when an artist goes international, and for that to happen, they have to have the right breaks.