-

Part I

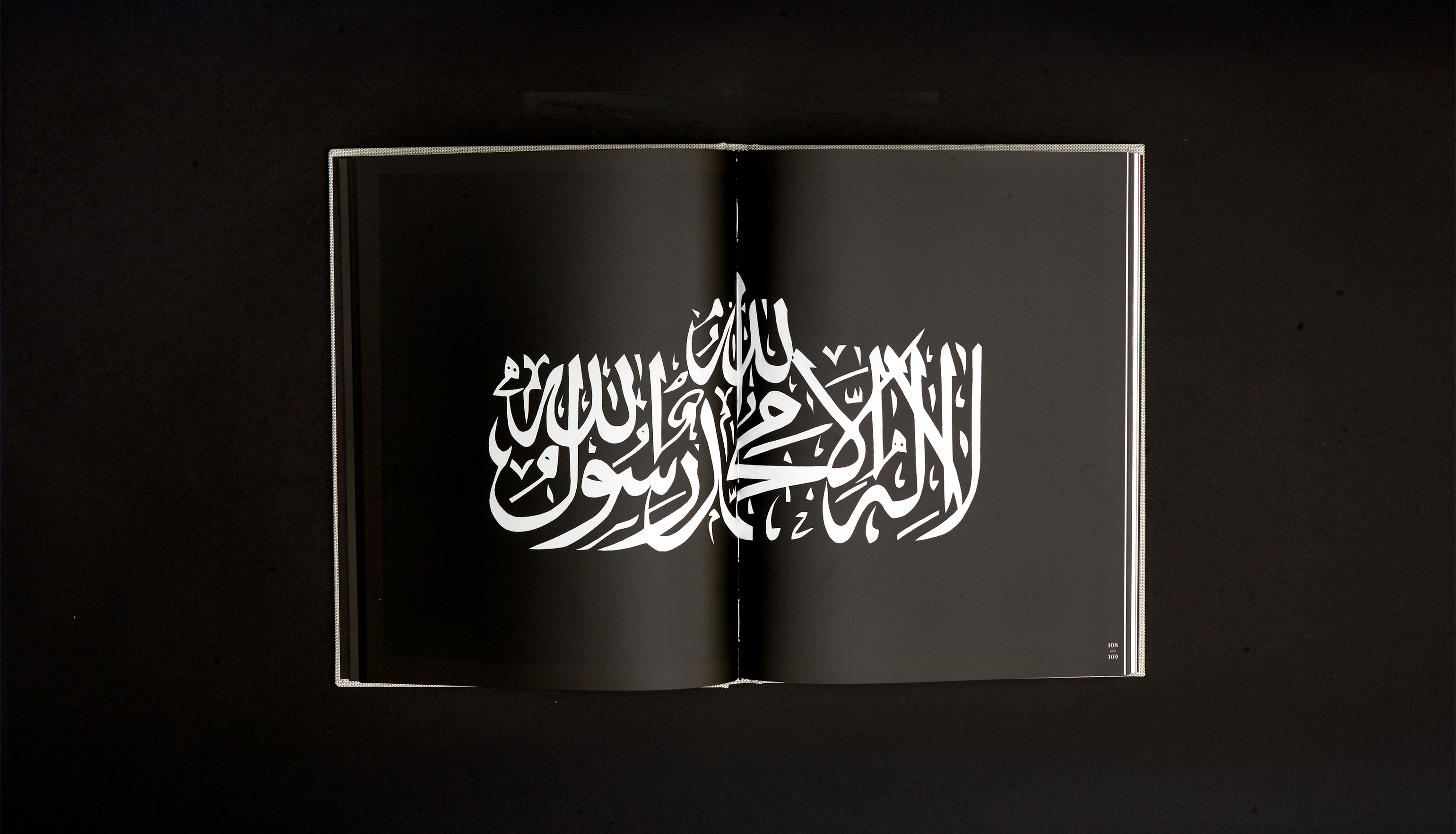

A conversation with Ashkenazi Jews – Why are you pretending? – Pretending what? – To be a Mizrachi Jew. – I’m not pretending, I am a Mizrachi Jew. – Oh, come on, you?! A Mizrachi Jew?1

A conversation with Mizrachi Jews – Why don’t you write that you are a Mizrachi Jew? – It’s inscribed in my name. – Well, then, why don’t you write about Mizrachi Jews? – I do. – What? Where? – Yigal Amir, Carmela Buchbut. – Oh well, that doesn’t count. Why don’t you write about your own Mizrachi identity?

The first series of questions is posed by a group of people who believe I am pretending to be something that I am not. The second group of people believes me to be concealing who I really am. From my own perspective, however, there is little difference between them. Both groups belong to the identity and language police, and both presume to know better than I do who I am and what I should be thinking and doing.

Every day, from first grade to the end of elementary school, my teacher would enter the classroom, open the attendance register, and read out our names. Azoulay was among the first ones. It was preceded by Abutbul, Abuksis and Abergil. These were the Mizrachi kids, the North Africans. I knew they were not liked from home. They were spoken of dismissively, and sometimes even called derisive names. They were inferior to us. My mother was a third-generation native of “the country” (ha’aretz) which cannot be named with its name, for she was born in Palestine, a name that would eventually become forbidden and cursed for Israelis. My father immigrated from France. We had been made to feel that our family name, Azoulay, which followed immediately upon these names, was different from theirs.

When I was about 12, the older of my two sisters suggested that we change our last name to a Hebrew one. This was how I discovered that our name wasn’t quite right either. It disclosed something, and others might think that we were like “them,” those with the other names. We were not like them. I understood, with a child’s intuition, that I had to support this plan. Yet my sister’s suggestion was rejected with the assertion that “One doesn’t change one’s name.” And in any case, my father is from France. The subject of our last name was never raised again at home. As an adult, I attempted to reconstruct this event, but my mother denied that my sister ever suggested changing our name.

My father is from France. This is a fact. And so we, his daughters, are eligible for French passports. The passport would attest to its bearer’s identity. Shortly before graduating from high school, I began preparing to realize my dream – that of studying in Paris. I began the procedure of applying for a French passport. My correspondence with French bureaucracy revealed to me in no uncertain terms that my father was an Algerian, a native of Algiers. I had already become aware of this detail when I was 12, yet had never internalized it. To the best of my memory, my father never spoke of Algiers. In general, he spoke little and told many stories. That was perhaps why I never asked about the gap between France and Algiers. My mother explained that when my father arrived in Israel in 1949 (emphasizing that he came as a volunteer to enlist in the Israeli army), and was asked for his place of birth, he replied with great care: Oran, France.

For years, I pictured that scene at the Ministry of the Interior, seeing it as vividly as if I had been there myself. My father leans towards the reception window. Facing him is the tired face of a bored clerk. My energetic, amused father utters a single word, “Bonjour,” in the hope that, as always, this greeting would open every door. The clerk seems less amused and asks him matter-of-factly for his place of birth. When he hears the answer, “Oran,” he pauses momentarily and asks with obvious disinterest, “Where is that?” My father repeats the name of the city and even doubles it – “Oran-Oran” – as if attempting to redraw the borders of the city. As he looks into the clerk’s eyes, the hint of a smile appears on my father’s dark face. He glances left and right, perhaps in order to reassure himself that no one is witnessing this case of geographical fraud, and then replies with great satisfaction: “In France, of course.” I liked telling this story every time I was asked about my family’s origins. It filled me with pride. I always emphasized how lucky my father had been to meet an ignorant or bored clerk. This was how I managed to ignore the deep significance of the fact that my father had invented his identity.

Several years ago, I wanted to anchor my version of the story in concrete fact, and mentioned it at my parents’ house. I probably dared to do so only when my father was out. My mother, at once offended and defensive of our family patrimony, responded by reproaching me: “Why would you say such a thing?! Dad is French. Algiers was part of France, and the Jews were the first to receive French citizenship.” This was the version told by my mother, a sabra as she called herself, a third-generation native. Words are commensurate with things and things commensurate with words. My mother couldn’t be lying. The truth, as far as she is concerned, is the proof that no lies were told. Truth is always conscripted in order to justify something, to anchor it in reality. Truth is subordinated towards the attainment of a goal that requires the performance of acrobatic feats. My father, however, showed no interest in truth. He didn’t feel compelled to prove to anyone that he spoke the truth. He simply enjoyed being French. It was a question of pure pleasure. Good wine, baguettes, camembert and cold cuts. After you bury me, he used to say, play jazz and eat French food on my tomb. Had it been possible, I think he would just as eagerly have enjoyed becoming an American – they had, after all, landed on the moon and invented jazz and the XXL life. He reserved the adjective “real”2 for jazz and food, but never for identity. Not even for a split second was he bothered by the question of whether his identity was truly French. In every encounter with officials, as he faced those who come to inquire about identities, papers, or taxes, he became incredibly creative. He reinvented himself over and over again, exploiting their weaknesses, their ignorance and narrow-mindedness, their one-dimensional outlook and their underlying motives. Regardless of whether he intentionally searched out this twilight zone or entered it by chance, he derived pleasure from being “there,” in a territory that was not clearly defined.

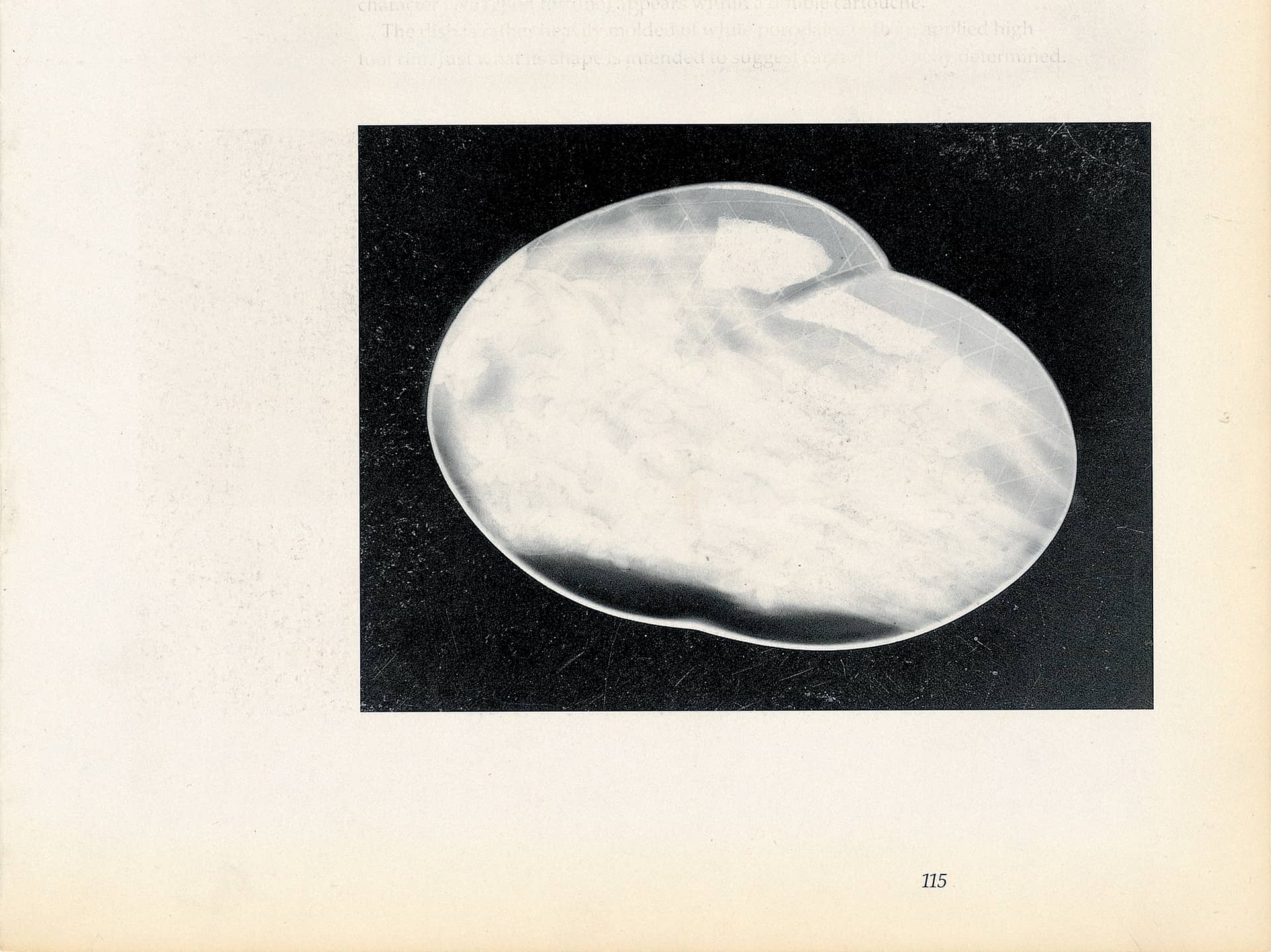

When I was 12 years old, my older sister came home with a booklet detailing the SHELI party’s platform. To this day, I can feel the touch of that slim booklet against my hand, the soft cover, the staples that held it together, the simple black print, a block of text with no pictures. I think the cover bore a monochrome, grainy greenish image of a sabra, a prickly pear plant, printed so roughly that its defining outline faded into the background. This booklet was where I first came upon the word “occupation.” It hit me with great force. It was unrelated to the little I knew about the place I grew up in, and about the deeds of the people who inhabited it. I remember several other harsh, violent words: expulsion, expropriation, theft and disenfranchisement. To this day, when I use these words, I feel in my mouth an effect similar to the one I felt the first time I pronounced them. Their foreignness in my mother tongue is given expression, above all, by the respect they demand. They cannot be camouflaged within language. As a child I felt that these words were too big for me to use, but also that I had the duty to pronounce them. The racist house in which I grew up amplified this sense of duty. I’m not certain about the memory of the prickly pear on the cover. It’s quite possible that I am imagining it now, creating a memory out of fear that the words I remember cannot aptly describe the shock I felt coursing through my body as I encountered this new vocabulary. The image of the perforated, punctured prickly pear being fading into the green background was so much more fragile then the prickly pear whose image was reinforced by my mother’s words every time she proudly declared: “I am a sabra, a third-generation native.” Up to that moment, I too viewed myself as a sabra. The fact that my father was an immigrant from Europe did not undermine the sense of being chosen to be a sabra that I inherited from my mother. She who was born in one of the colonies founded by the Baron de Rothschild, and her body, language and gestures embodied the sabra identity. Even when she used words that were gendered female, she was a female sabra created out of the rib of a male sabra, and she brought her daughters into its covenant. My father always remained different, his distance at once foreign and elegant.

The discovery concerning my father’s origins and the discovery of the acts committed by Zionism – which was in fact a discovery concerning my mother – took place around the same time, but they did not carry the same meaning. My mother’s truth was stripped bare before me and revealed to be a lie, while I grew increasingly fond of my father’s lie as a form of truth.

-

Part II

Despite the distinct nature of these two stories, the one about my father and the one about my mother, I held my mother responsible for both. My father’s lie harmed no one; it did not attempt to control or conscript other subjectivities. My father lied because he took pleasure in the possibility of becoming French. He never experienced a similar pleasure vis-à-vis the possibility of assuming an Israeli identity. Although he was familiar with it and adopted a patriotic political stance, he preferred the French Club of Netanya, the Quatorze Juillet (the Bastille Day) celebrations at the French ambassador’s house, and the tricolor over the blue-and white Israeli flag. He did not attempt to rid himself of his heavy French accent, detested the popular Israeli music and rituals of cracking sunflower seeds, eating hummus, and grilling meat outdoors. He scolded customers who dragged their feet when entering his music and electronic store, which he treated like a palace, and never conceived of going out to wash his car in anything but a collared shirt and gabardine pants. My mother insisted on her truths concerning both my father and Zionism, and she derived pleasure from her righteousness.

Like every national discourse, my mother’s syntax built upon a silent consensus among those who spoke it. Hers was the language of the occupiers, a language that could not afford to let uncultivated areas develop, from which alternative narratives might emerge. The fundamental agreements demanded by such a language preclude the possibility of breathing within it. Polemics are encouraged within preordained oppositions contained within the Zionist meta-narrative. For this reason, listening to external voices, let alone adopting them, constitutes a betrayal of one’s mother’s tongue; alternately, one can seal one’s ears and exile oneself to distant lands or invented worlds. My mother was a native sabra. The fact that her beloved mother, my grandmother, was born in Bulgaria and came to Israel by chance, that she hardly spoke Hebrew until her last day and always remained somewhat distant, a foreigner, did not impact my mother’s image of herself as a real sabra.

Around the time of this discovery, I turned 12. Without being able to account for it verbally, my body was continually irritated by encounters with truth agents. Schoolteachers, youth movement counselors, politicians and neighbors were all contaminated by truth that can be recognized only by and amongst Jews. They all lied. “National home.” “Ours.” “We were persecuted.” “All Arabs are murderers.” “All they want is to drown us in the sea.” “It’s their fault.” “They fled.” “They have no problem killing one another.” “They multiply like flies.” “We fight for the life of every one of our soldiers.” For the first time in my life, I began experiencing rage. Rage concerning the place I grew up in, the tragedies it produced and about which I still knew very little, the lies used to camouflage them. My rage was mixed with a sense of insult. Perhaps because I had been misled. I didn’t know where to turn for solace. During that time, I was gathered up in the cold arms of an orthopedic posture corrector designed to straighten my back. This contraption, which was supposed to efface ancestral sins, condemned me to silence. A silent mouth and a silent body. In one instant, the “we” that I had been part of was transformed for me into “them.” Years went by before I understood that the traces of my father’s otherness – which was always there, omnipresent – had also been impressed upon me, giving me the power to see myself as distinct from them, even though they had changed.

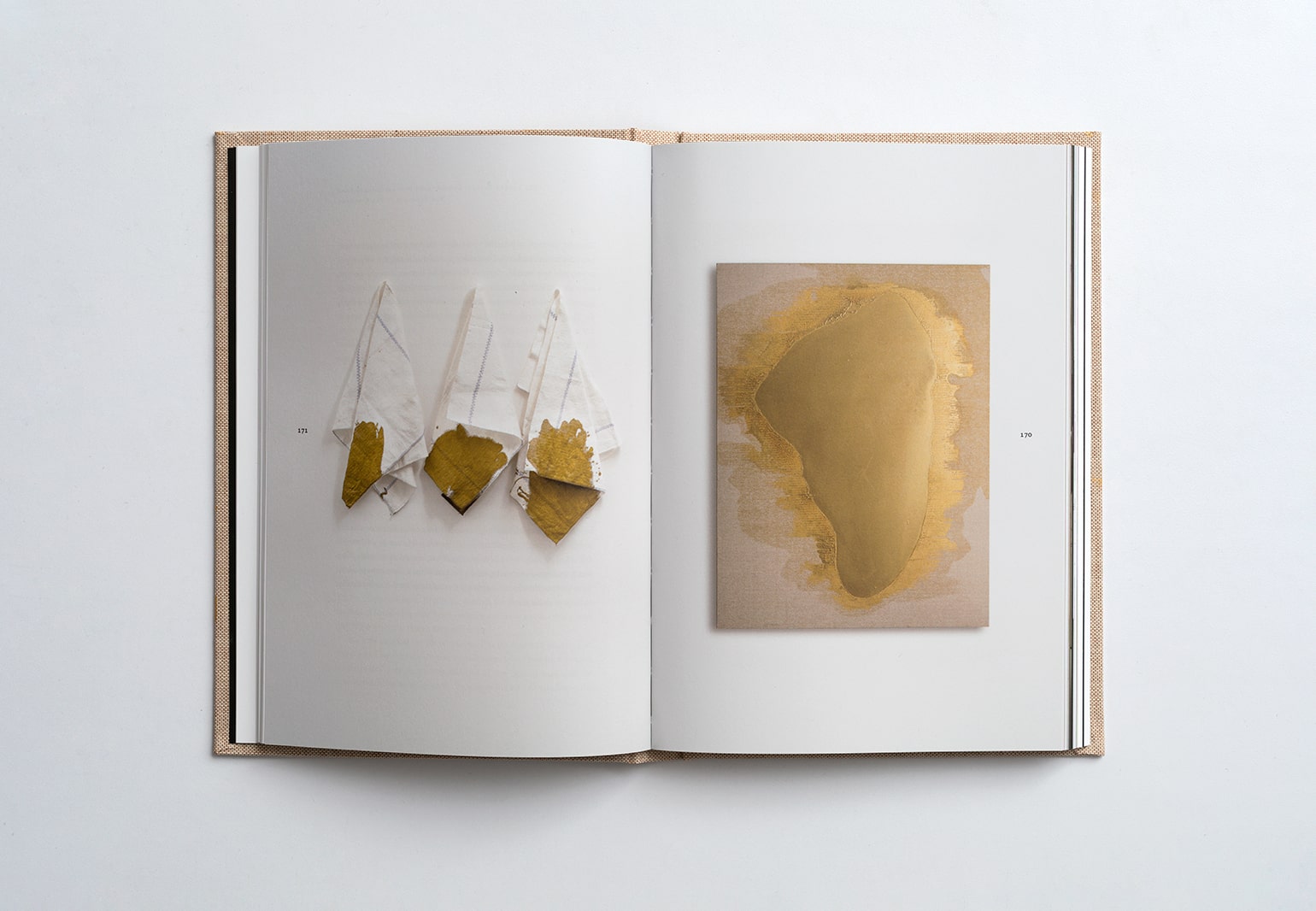

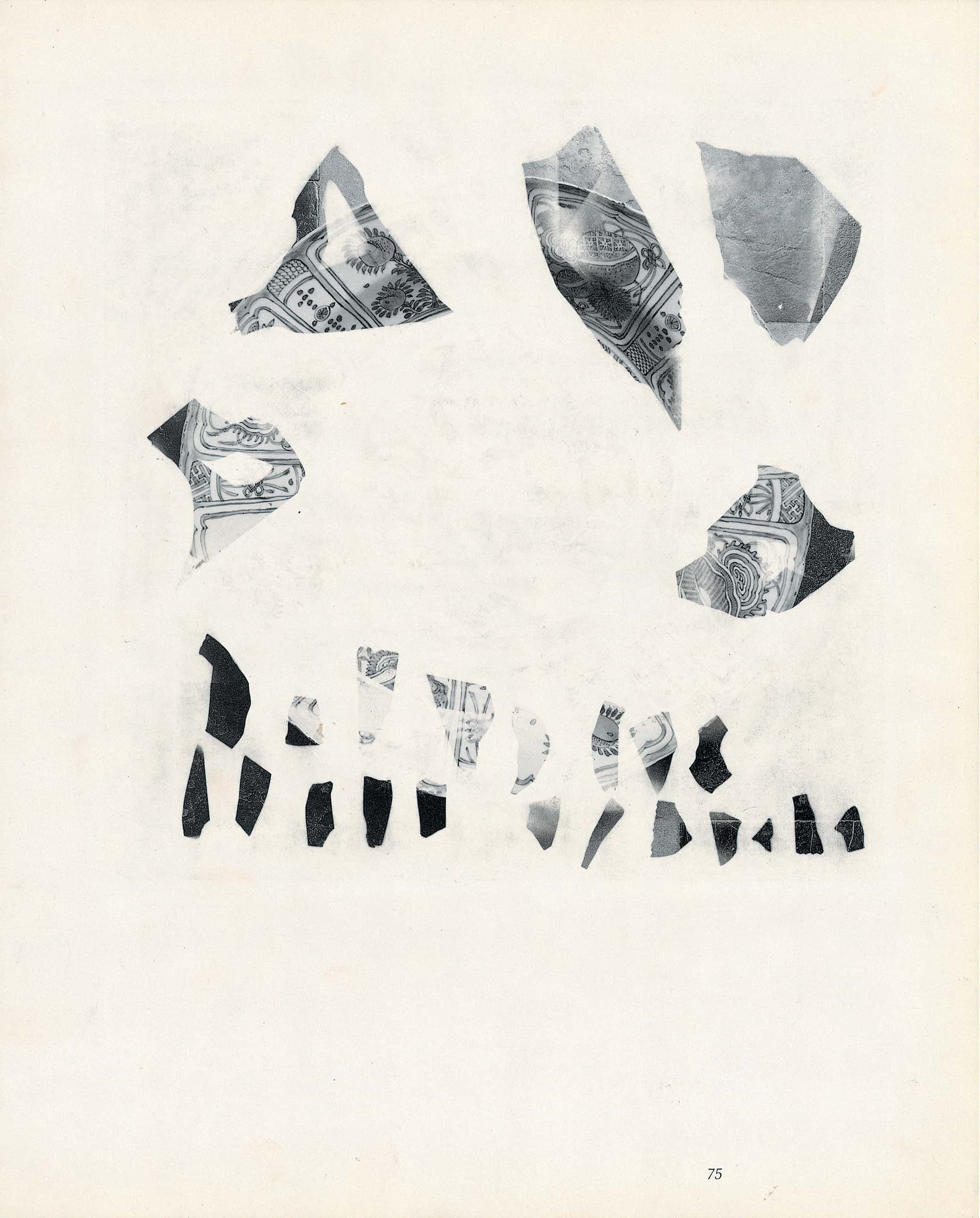

The journey I was forced to embark on, a journey outside the realm of “we,” divested me of language. The orthopedic cast fitted onto my body in Dr. Barzilai’s store on Tel Aviv’s Sheinkin Street tightened its grip around me, surrounding the place from which words originated. I discovered that I knew how to remain silent. Silence revealed to me its rehabilitative potential. The metal poles, leather straps, and plastic pelvic mold rattled and clicked proudly – new, clean, technical syllables. These were the building blocks of a non-native language. With my mother’s language, as with any mother tongue, a perception of history as reality, as a matter of fact, is given through its syntax and its organizing categories. My mother’s own mother tongue was Ladino. She guarded it zealously, wishing to share it with no one. For years I underestimated the importance of this part of her life, and only years later I understood the Ladino was her nature reserve circumscribed within a quintessentially Israeli life. Years went by before I realized that what I had identified as my mother’s sense of belonging to this place was more precisely a response to a command, to a pressing need, to being called to the Israeli flag, purely out of duty. As if on a mission, she sought to introduce us into the covenant of the sabra, while she herself did not entirely efface all traces of her own diasporic existence. On the day that her mother, my grandmother, passed away, the sounds of the Ladino I did not speak vanished, leaving behind nothing but my mother’s unconcealed longing and several terms of endearment. For us, my mother sought to reserve the local, purely sabra mother tongue. She wanted our family to perform gloriously for the state of Israel. We were always being observed by an additional eye, the eye for which we ate, celebrated, dressed, went out, and hugged. For moments, we embodied the achievements of the Jewish state. This heavy burden was not merely a kyphosis within language. For us, daughters and sons of the second generation of expellers, it more closely resembled a skin disease or contaminated blood. We were not present at the time of the foundational crime, and did not launder our words. We inherited them as sparkling white and carefully starched. When I tried to purge this language, I discovered to my surprise that I was close to its bottom, wholy submerged in shallow waters.

My father’s tongue was punctured. The stories that percolated within his Hebrew were intriguing in terms of their accentuation, yet his Hebrew lagged far behind. The richness of his imagery was not born in Hebrew. At the same time, his functional syntax and impoverished vocabulary did not impede his talent as a storyteller and his ability to pay attention to details, to the atmosphere, and to the characters by means of which he repeatedly reinvented himself. These orally transmitted stories glossed over his broken Hebrew. Nevertheless, every time he rose from his armchair and went out into the world, even if just a few meters away, he came back with new bounty. Reality never disappointed him, and he always found fragments to piece together. The fact that his tales transcended his listener’s field of vision allowed him to gather materials whose authenticity remained unchecked. He had a penchant for details, and as incredible as his stories sounded, they were always somewhat based in reality.

I have a vague memory, I cannot pin it down with certainty. One day someone commented on my father’s poor Hebrew. In retrospect, I realize that this was the moment when I began behaving as if the countdown had begun. I had to cater to my totally unfounded desire to read all the books. I was still just in my early teen years and had my own library card, but was only allowed to borrow three books a week. There were hardly any books in our house. I made a point of taking out books whose opening sentence I failed to understand. I read them without really reading. I wanted those other words, the ones I did not know, to become mine. I enjoyed the fact that my sisters took pride in the books I read. I enjoyed the way those books kept me company, gradually drawing closer to me. Or I to them. I liked their feel, their presence on my pillow, the sense of security they imparted. Much later, I came to understand that it was easier for me to read a book after it had spent some time in my company, and this has since become a habit. I purchase books knowing that it will take some time before I read them.

My mother tongue was contaminated. Words dulled the pain – all pain, including that of the mother herself. They clamped the pain’s mouth shut. Rather than listening to the pain and engaging with it, my mother tongue argued with it, spoke in its place or for it. My mother tongue is contaminated. Hebrew is contaminated. The Hebrew mother tongue is contaminated. My Hebrew mother tongue is contaminated.

Both within and outside of language, I felt the same sense of helplessness. My attempts to extricate myself from my mother tongue failed, and my sense of unease would not abide. I was ready to bite into my mother tongue in order to then watch it collapse at my feet, defeated and humiliated after all it had instigated. Yet I loved the language, I loved the mother. I too began to use it to invent things, to tell the story of the past forwards and backwards, sideways and in a circular manner, until what had been buried awakened to life and what had been neglected became central, like the heart, or the spine.

My father tongue was a gesture. A gesture of impersonation, otherness, foreignness, masquerading, multiplicity, practicality, acrobatics. This gesture repeated itself in every language my father could chat in, as he did with the various customers who came to his store. He took pleasure in his ability to register words in foreign languages and to behave as if he spoke them – Amharic, Russian, Arab, Spanish, and even Yiddish. I possessed no father tongue to immigrate to, but I possessed the gesture. At first it was bodily, and then gradually it became a written language, and only later a spoken language. My father’s acts of fabrication were so powerful that even when it was clear that his life was not as colorful as his descriptions, they continued to exercise a certain magic, that instilled within us the power to extend their use even in his absence. His physical death will not take it away from us. We have internalized this imaginative faculty as if it were our own, in order to elude that which attempts to bind us.

In addition to the gesture of speech, my father tongue also contains the gesture of silence. It is silently present like a scar. During the Second World War, my father joined the French army and left Algiers. When he immigrated to Israel he left Algiers a second time, and this departure was final. Today I see this act as an act of survival. Who could possibly have wanted to be an immigrant from North Africa in Israel in the late 1940s?! What sabra woman could have possibly wanted, at that time, after the expulsion of Arabs, to marry an immigrant from North Africa, especially if she herself, with her blond hair and green eyes, had successfully camouflaged her Sephardic origin? When he was referred to as an Algerian my father felt he was being taunted, whereas when he was referred to as French he felt he had received a complement. He avoided the friendship of other immigrants from North Africa, took care not to be identified with them, and insisted on marking the distance that lay between them. The price he paid for this insistence was loneliness. He was a foreigner, and this experience of foreignness remained a solitary one.

-

Part III

A decade or so ago, my parents presented me with a tape that had been recorded in 1972, in the course of a family car trip to Ashdod. I remember that trip. I was nine or ten years old. My father was driving, my mother sat beside him, and my youngest sister and I sat in the back seat with my maternal grandmother. As usual, I was the one holding the microphone. In contrast to other such tapes that vanished over time, this one was preserved because it had recorded the voice of my grandmother on the day preceding her death of a stroke. When I listened to it 30 years later, I could only guess that the woman with the heavy accent, which was likely Bulgarian, was my grandmother. That was not how I remembered her. Her china-white face and black hair have remained voiceless in my memory. Voices are fated to be erased from photo albums, and the same happened to my grandmother’s voice. The other voices that emanated from that tape sounded equally unfamiliar. The little girl in the car – the girl who was me – implored the others: “Talk to me.” It seemed to me, as I listened, that she repeated this request more than once. Listening to this imploration, the noises all got mixed in my head and I could no longer hear a thing. I have since held that tape in my hand and slipped it into the tape recorder several times, yet I never dared to hit the PLAY button. I was struck by the distillation of my entire life into those two words – “Talk to me.” The little girl whose voice rang out on the tape, giggling and protesting, reminded me that my intellectual interest in the drama of speech and silence – this neverending dialectic of ownership, belonging, responsiveness, apprenticeship, pronunciation, foreignness, loneliness, anxiety, disenfranchisement, betrayal, silencing, effacement, compatibility, and immigration – was preceded by an act written in the body.

The gesture of silence hid in my body like a genetic code even before I was cast out of, and fled from language. This gesture enabled me to reinvent myself. Many years went by before I realized that even my mother, whose speech embodied collective Israeli identity, who spoke for it and brandished its flag before us, also fled from it, to her own living room. There, as long as I did not provoke her, she forgot all about it and her duties towards it. Together with her husband – my father – she could, in her own living room, permit herself, for a limited period of time, to experience her own sense of estrangement from the others – the Israelis, to participate in his evening aperitif ceremony and in her own sewing-related mannerisms, to dream about her family’s mansion in Sofia and to take refuge in the European rituals of courtship that my father undertook for her sake, masquerading as a Frenchman. Yet in her own living room, she would also occasionally use a colloquialism from the world of her childhood in Rishon Lezion, demonstrating to us that beneath this European sheen, was a “real” sabra.

When I began asking questions about the Palestinian washerwoman who had worked for my mother’s parents in Rishon Lezion, and who must have taught my mother the impressive number of Arabic words she knew; or when I wondered what she thought when, one bright morning, my grandfather’s Palestinian workmen did not show up for work in the orange grove, I encountered a one-dimensional embodiment of a sabra. The voice of the nation emanated from her throat, replacing the woman who raised us most days of the year. Speaking in this national voice, she sought both to deny the fact that a crime had been committed and to set me back on the straight path, to redirect me to the vantage point from which I too would continue to ignore the crimes that had transpired.

The day I began inquiring about the past, and was branded by her a rebel, my mother could no longer speak to me as a mother to her daughter. It was forbidden to question the road that had been taken – the road she considered to be beyond questioning. My act of heresy opened up a great and painful abyss between us. Only after my mother’s death did I come to realize that by responding exclusively to the figure of the sabra, I endowed her with more power than she really had. I could have possibly undermined her power, had I allowed my mother’s own sense of estrangement from this place to reveal the cracks in this figure. This sense of estrangement, I still feel, protected her from the abyss that must have opened up with the vanishing of her childhood landscape – of the characters, customs, forms of dress and flavors of life in her beloved Rishon LeZion – where, up until the foundation of the state, the lives of Jews and Arabs naturally intermingled. And from that moment onwards, a hollow language of independence and liberation took the place of the pain, loss, and destruction. Had I asked her about this sense of estrangement, her sabra self would probably have denied its existence; remaining silent about what she could not share with a traitor like me out of fear that I would turn her words into a testimony about what had been concealed. This sabra self would probably have denied the estrangement, as well as the meaning I ascribe to it today. It is possible that the noun “estrangement” does not adequately describe the thing I am attempting to capture, the inner lining, visible or invisible depending on the circumstances, of the sabra – who, rallying to the flag, denied its existence and trampled it with her own two feet. I am not imagining this sense of estrangement. It had obvious expressions, even if she denied their significance. By touching upon it, I am allowing for the possibility that my mother experienced a terrible sense of loss when the country, of which she so proudly declared herself to be a native, was suddenly transformed. I refuse to believe that my mother did not identify the catastrophe as such prior to adopting the hegemonic story that justified its occurrence and denied its meaning. Had she not experienced an unspoken, painful, silenced loss, she – and other members of her generation – would not react so tensely, their speech tightening like a protective wall in an effort to conceal that sense of loss; readily denying its existence and replacing it with a false joy concerning the foundation of the state in a country taken from others. Had I not delineated the contours of this sense of estrangement, I would not have been able to imagine the possibility of a civil charter, the possibility of responding differently to the catastrophe that has also overtaken the lives of those who became the oppressors and their descendants, continuing to hold them in its clutches. Perhaps if I can reconstruct the seams of the lining I can also unravel them, rearrange the pieces of cloth to form a new configuration. Perhaps I can hear her speak to me, with me, hear her saying “Yes, I miss the washerwoman’s gaze, her heavy accent, the special sound produced when she rolled my name – Zehava – on her tongue”; and perhaps after a short pause she would add, “Yes, and the feel of her hand when she would caress my golden curls and gather me up in her arms.” From that point on, Mother, the conversation would start flowing and you would regain the vitality of one who is no longer exerting such an effort to conceal a buried secret.

When one is surrounded by a roaring silence as regards the past, the words “Talk to me” express a longing for speech. When one is surrounded by the rustle of speech, the words “Talk to me” overwhelms the existing discourse. exposing the fallacy of discourse that does not address “me” but rather a candidate for military service. Speech uttered by someone whose voice has been assimilated into the voice of the nation, that does not address a recipient – is not speech at all. These three words simultaneously demand both an act of speech, and an act of silence.

As a child, I tried to assume the role of my father. I did not choose the role of the storyteller, but rather of the one who falls silent between stories. I had to overcome the tremendous urge to speak that had defined me since my youth, to choke back the tremendous number of words that crowded in my mouth. I thought of silence as something beautiful. I considered it to be a sign of nobility and pride. I felt that distress, pain, sadness or longing were mitigated in its presence. I trusted it.

When I was 18, I began studying French. During my first two years as a student in Paris, life outside of language was no longer a metaphor. The new silence of an immigrant who had lost her tongue enabled me to rediscover myself in language, in a foreign language, which enabled me to reinscribe language into my body.

The one who spoke French was different than the one who spoke Hebrew. Several years later, the distance between them was gradually reduced. French enabled me to return to Hebrew, yet the joy that spontaneously fills me the moment my lips prepare themselves to speak in French, infusing my speech with life, is a joy that rarely arises in Hebrew; and even more rarely does it arise spontaneously, of its own accord.

The orthopedic body was locked in a state of silence. The demand “Talk to me” belonged to it as well. It too attempted to enter language. To be spoken to, even when it faltered, even if it did not respond immediately. It demanded time, it asked not to be abandoned, to be spoken to until it caught up, closing the gap between word and body. It did not attempt to efface the signifier impressed upon the body, but only to expose it to the air, centimeter by centimeter, through speech, direct speech, speech directed at me, directed at the body, reinstating it by means of the tongue so that word and body could be reconnected on a scale of one to one.

The sign impressed upon the body cannot be removed. One can refuse the signifiers that are being offered, and say “No thank you” and search for an alternative signified. “No thank you, I am not interested in writing about Mizrahi identity, I have no idea what identity means.” “No thank you, I am not interested in forgetting that I am a Mizrahi woman.”

The sign impressed upon the body is devoid of content. In my case, it is rooted in language and in the linguistic gesture. Hebrew will not let this sign rest in peace. It awakens from its place of rest, as if it cannot rest under such conditions. The sign entertains the process of negotiation with language; a process that will continue as long as the sign’s foreignness is preserved, persisting despite the constant and pervasive threats and demands to assimilate, to conform to the existing covenant, the one that exclusively binds those who are not foreigners, whose closeness is a function of the divide established between them and the others, enabling and justifying small and large acts of theft and expulsion.

In contrast to a large number of Mizrachi boys and girls, I suffered little because of my origins. The few insults directed at me were revealed to me retroactively, when I understood that the dismissive attitudes my parents directed towards other Mizrahi Jews whom they perceived as ‘backwards.’ On the day I experienced the meaning of these insults, they stung with the immidiecy of the present. At the same time, they imbued me with a clear perspective, a power born from searing pain. Being Mizrahi as it was impressed upon me by my parents had no content; yet its encounter with the outside world forged a clearly defined stance, and an inscription in the body which combined with certain choices, determined my place in the world. These choices expressed the desire to resist preordained fate. Fiction and the imagination, foreignness and immigration, the intentional blurring of their traces and the silent and silenced presence of their signs played a decisive role in determining that a contingent definition – the daughter of Mizrachi parents – began to exist as a juncture of intentional choices. And these choices themselves began to appear as an arena of negotiation in which what could have been preserved as a birthmark, a cultural disability or a form of civil distortion became an asset. I would grow over time to see this asset as a gift, as what saved my life, extricated it from the slot allotted it by the melting pot mentality, which continues to view the place where I grew up as multiculturally open and not as the space of segregation that it is. This gift resembled a smoke detector, a warning device that alerts the body – at times even prior to the formulation of a verbal statement – to the fact that this is not a place where exiled communities come together, but rather one where those whose outlook is incompatible with the collective mentality are excluded or exiled. A place where responsibility for the act of exiling is denied, and where the gaps through which one may catch a glimpse of another form of existence, or an object of longing, are inaccessible. The detector did not operate of its own accord. Its familiarity with the injustices suffered by those around me, of those impressed on the skin, did not ensure its response in those times and moments where it should have wailed like an alarm siren and struck out. It required me to work for it, it demanded bits of information, facts, pictures, artifacts. Every time I managed to retell a story that was seemingly familiar, to rearrange its different parts so that what had been denied or concealed was reintegrated into it, I felt like a person whose life was saved. Saved from collaborating on a crime. I could not feel this threat in real time, because its essence centered on the concealment of its nature. The understanding that without the painstaking labor of storytelling I would not know what had transpired in the place where I grew up, came in waves. With delays, and often retroactively, I understood that I had became a partner in the denial of a great catastrophe that had taken place before I was born. This catastrophe was distinguished by the sudden and unexpected impact it had on its direct victims, and by the lens it implanted in the eyes of those responsible for it and their descendents. This special lens does not easily shatter. It is cracked mainly by experiences of foreignness and estrangement, which allow for an examination of the hegemonic narrative that comes from the outside. It results from one’s recognition of the shrill notes, seams and gaps that remain invisible to the perpetrators. In a society where acts of expulsion, exiling, and occupation are defining patterns, the sense of estrangement that surrounded me while growing up served as a key for imagining a different model of citizenship, a covenant between strangers and estrangement. My mother died and now my father is also dead. I will introduce them into this covenant in my imagination.

When the mother tongue is contaminated, when the father tongue is punctured, one can imagine a civil charter only if one recognizes that this is the hour of what has been erased as a viable possibility, the hour of what is now becoming possible.

Venice Biennale For Architecture, Artis, The Jack Shainman Gallery, Printed Matter Art Book Fair, Alon Segev Gallery, Chelouche Gallery, Braverman Gallery, UMapped.