11:40

Geert van Kesteren (1966) is a photographer from Amsterday, currently based in Jaffa. His photography is acclaimed for a cinematic feel of storytelling; an author with a camera that gives insights into the psyche and soul of conflict. His landmark books, ʻWhy Mister, Why?ʼ and ʻBaghdad Callingʼ about the war in Iraq, serve as a new model for the possibilities of engaged and innovative documentary. Below is the transcript from the film.

___

For the last thirty years, I visited fifty, maybe sixty countries; crisis conflicts, pandemics, tsunamis, earthquakes.

I see it as my job as a photographer to make images that you can relate to, because images are the bridge between cultures and misunderstandings. And it’s extremely powerful because it’s a visual language that everybody can understand.

I have always felt like giving voice to people who are not being heard. And as long I, I have that feeling I feel I’m literally in the right place. During suffering and during war, also a lot of good things happen, and I’ll give you an example, something I saw during the Tsunami in Indonesia, where I was quite early on. I made a journey by foot to a small village called Lupu, and that village had 1200 people. Except 30 men who were at work, everybody died. The only thing they still possessed was a wallet, with the money there was in it, and the key to the house – but there was no more house and there was no more doors. And there was one guy, an older guy. He went to town, took a loan from friends and people he knew, and he just re-opened the store there.

Six months later I came back. He was also married to a woman who also lost everybody. In all this destruction and all this sheer sadness there is the ability to bounce back. And I never understood how we do it as human beings. I never, I’d never got it. And there, I found an answer because I saw it.I see that it can be done. So no matter what we go through, we can bounce back. And, and that’s truly, really amazing.

A lot of the photo stories I make go into the drawer so to speak; and that’s where I felt the need to start making books. Like in Iraq, one of the assignments I never got – I worked there for Newsweek and Stern, but the one story I was not allowed to make was more or less about the suffering of the Iraqi people.

Audio Note from an Iraqi Woman: “I had to leave, but Baghdad gives you three options: Be a thief, or be killer, or kill yourself. I don’t want to be a thief. I don’t want to be a killer. I don’t want to make a suicide, you know? I want a better life because I feel I deserve it. And I think Western people,they don’t actually believe that we are really human beings. I don’t mean all Western people. I mean, those who don’t know us, they don’t know what we have been through, so they don’t think we deserve a better life.”

At the beginning, people were cheering the Americans, who many Iraqi’s saw as liberators. If you’ve been at the mass graves, and saw that the Americans enabled the Shia to finally bring their loved ones home and give them a proper burial. It makes you wonder why, why, why all this hatred against the Americans?

What happened there, in these months that came after that? And I think that’s what my book is about. And this is also why the title of the book is so significant. The title is “Why Mr. Why?”, I saw it written at the toilet in an American base, and I saw how American soldiers use this phrase as a taunt, like one American soldier asked the American for cigarettes and then the other and smiled and said, eh, Why Mr., Why? But this was obviously a very serious thing that the Iraqi asked the American soldiers while they were raiding their house, for example, or were passing by even, “Why Mr., Why? And I felt that it was the perfect title for the book because that’s what you wonder if you’ve been there so long, why? It’s difficult to comprehend, isn’t it.

There’s a filmic rhythm in my work, its not about this one iconic image. I think you need a wider story, you need to know what happened before? What happened after? So this whole idea of about a decisive moment, it’s my business, but I’m not all about it so to speak. I collected I think 10 or 16 stories that were really significant, like when the United Nations Headquarters in Baghdad was bombed, and this was the day when all the NGOs left Iraq.

I tried to blend in and I try to be invisible, and the moment I photograph, what I always see is that people just keep doing what they are doing. I always feel like in a weird way there is some agreement with people, when you photograph them, it’s as if they tacitly acknowledge that now you can be a voice. At least somebody might listen now, as a result of this image.

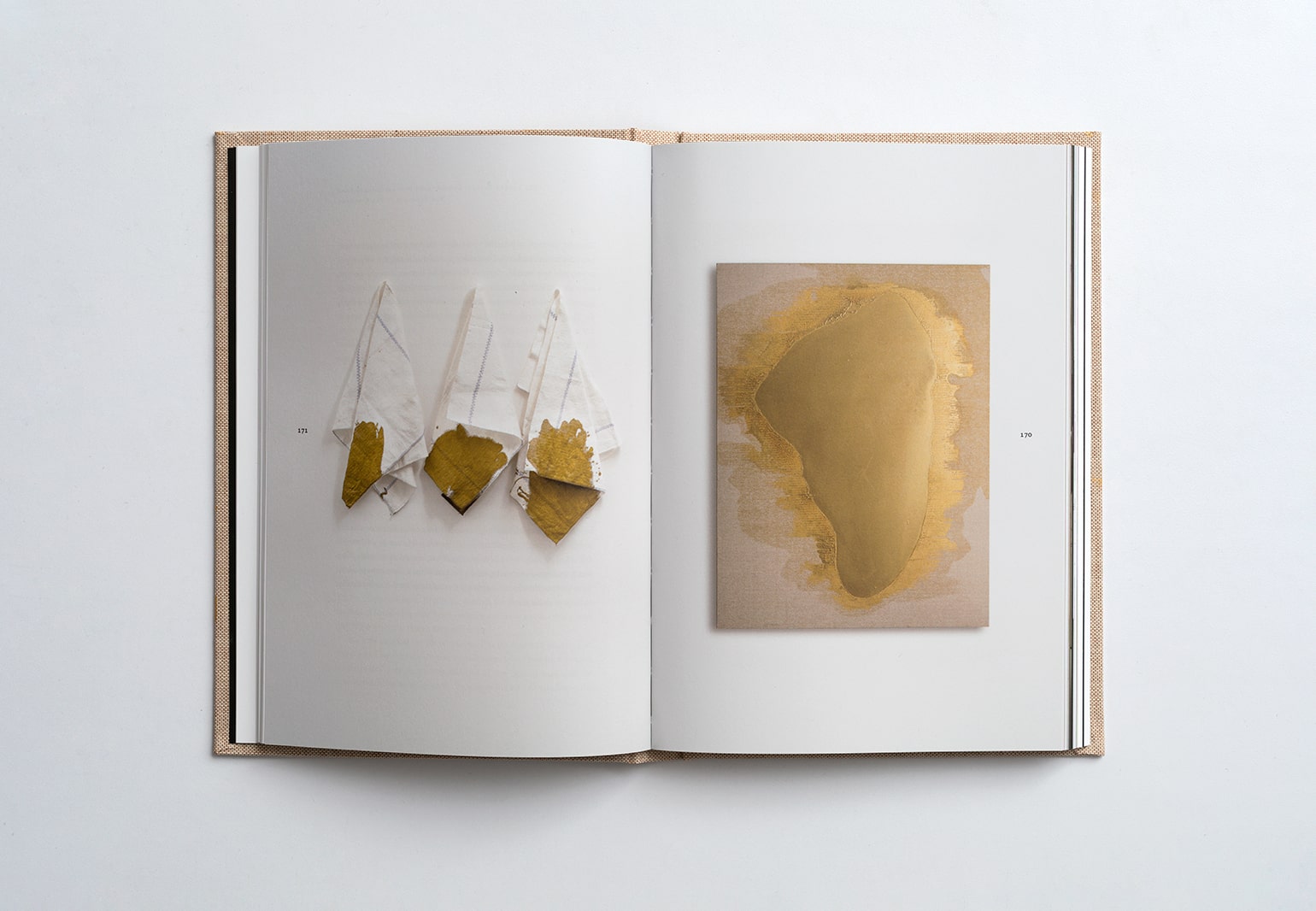

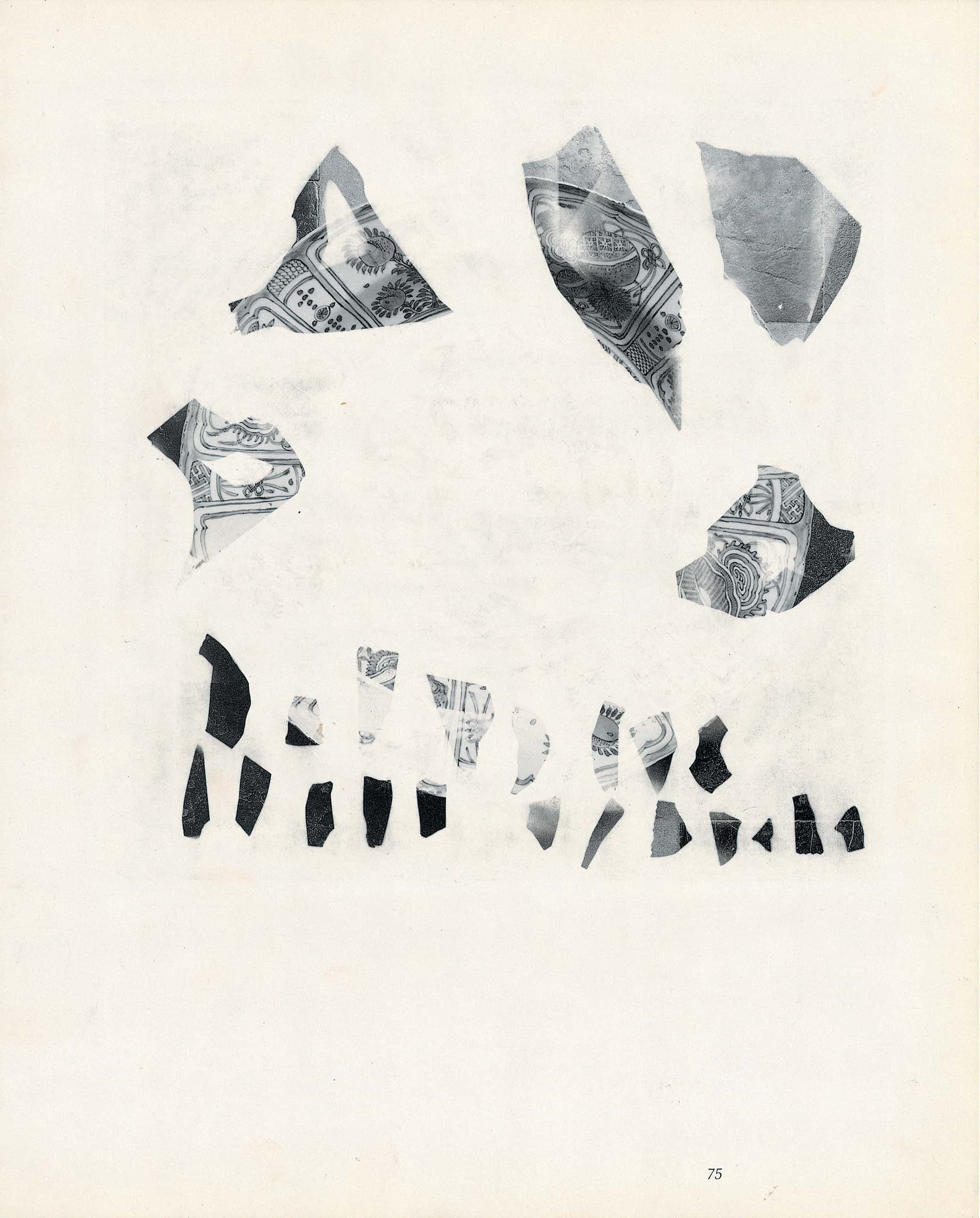

I came back from Iraq after ten months; I had the pictures, I had the title, but now how to make it. My designers Linda and Arman Van Deusen saw the work, and they understood that I photograph more like a filmmaker. So they really wanted to make this very thick book, we decided to include many pictures. We chose the thinnest paper that would’nt shine through. They kept the edges of the pages untrimmed as with newspapers, expressing more or less the immediacy of the story. Later it won awards and became popular, so I was invited to make exhibitions and it just grew from there.

A few years later, I really wanted to know what was going on there. Now there were millions of refugees from Iraq – people were leaving, and I understood that would be impossible to travel to Iraq, so I found a new way of getting the report out, and I thought, let’s start with the refugees. Let’s ask them, why did you leave?

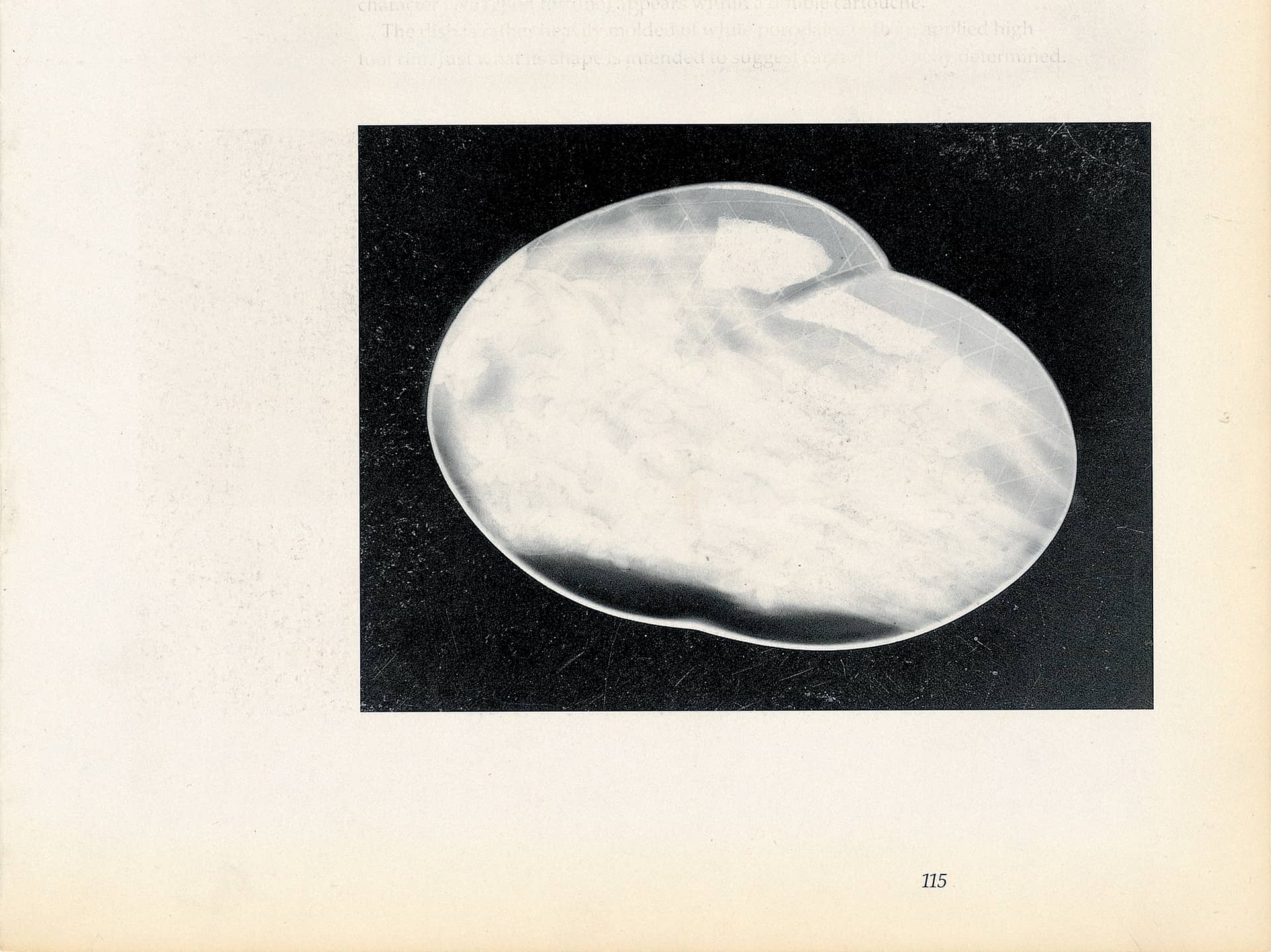

I published ‘Baghdad Calling’ a few years before the Arab spring, before the mobile phone became so important and civilians started using their phones as a media tool. People were telling me the same stories all the time, but I didn’t have pictures. One night I visited an apartment with five Iraqi doctors who had left the country, one of the doctors took his mobile phone out of his pocket, and showed a picture of a friend just before he had died. And I looked at that photograph and I was like, wow, it is so powerful. This is so meaningful. These are the images I’m looking for. It was highly controversial. When I published Baghdad Calling, the journalism world really thought I had gone bezerk, but actually it was about telling a story. It was about telling us. Through my work I’ve seen a lot of devastation, and it makes you wonder who we are.

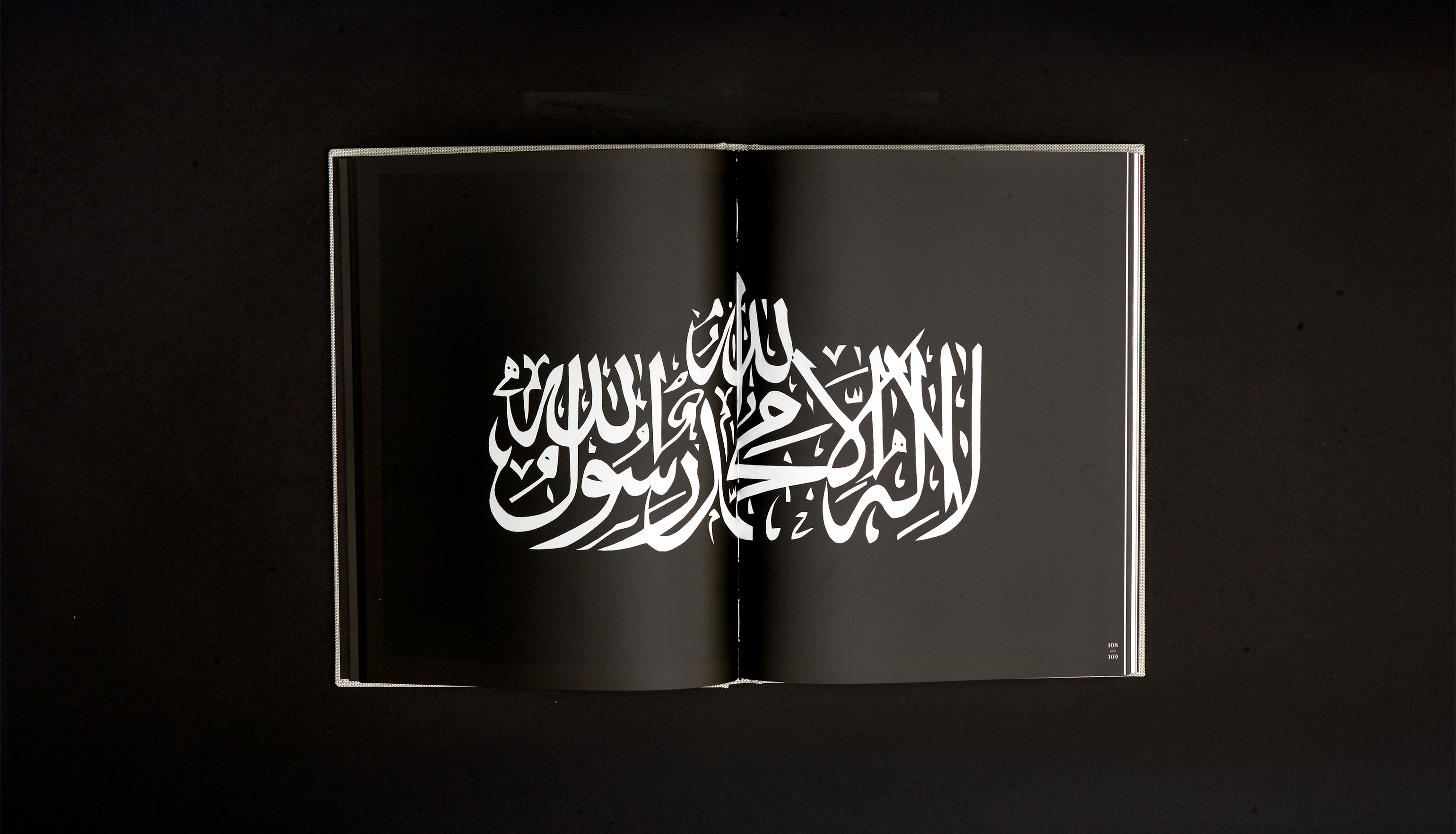

Belief is not something religious, it can be found in secular contemporary life. The way we are using our phones, the way we read our Koran or our Bible, belief is about a higher power telling you what is good and what is bad for you. Something really big changed in mankind, and we decided to think by ourselves, and with artificial intelligence in the digital age, it seems like we’ve make a U-turn, because it’s not me who decides who I want to vote for or what I want to eat, no, its artificial intelligence that comes from gathering data.

Life is unpredictable. If there’s one thing I’ve learned over all these years, life is truly, totally unpredictable, and we better take care of each other. I think that’s the most important message. We have to take care of each other because. Today you are the refugee, but tomorrow I can be the refugee. Today you are the victim, and maybe I’m the perpetrator tomorrow. This is how unpredictable life is it’s unbeleivable. It can flip like that. To see humanity, I think that’s the essence we have in life.